The Enigma of Gordon Walters' Art

MICHAEL DUNN

There is an element of mystery surrounding the artistic career of Gordon Walters. Many people would connect his name with only one type of painting: the 'koru' motif works on which his reputation rests. And few would know anything about his stylistic evolution. Yet, when Walters first exhibited his distinctive works in Auckland in 1966 he was no young painter having his first show; nor was he a late starter turning to painting in mid-career. He was forty-six and had been painting seriously for twenty-six years. Surprisingly, there has been little curiosity about this phenomenon: as if it were the most natural thing in the world for an artist to emerge fully mature and unheralded. What was he doing before that pivotal show at the New Vision Gallery? The little written about Walters does not say enough to answer that question.' My immediate aim is to explore some of this uncharted territory - with the idea of giving a fuller understanding of his art.

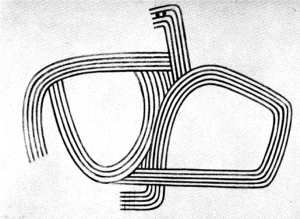

GORDON WALTERS

Drawing 1947

pencil 290 x 374 mm.

Born in 1919, Walters grew up in Wellington between the wars in as unlikely an environment for studying contemporary painting as you could find anywhere. Although there was nothing very stimulating in the art gallery, at least the museum (on the ground floor of the same building) had a superb collection of Polynesian and Melanesian art. Not that many painters schooled on British lines would have seen these collections as art, or would have noted the connections with contemporary European abstraction. later, Walters was to find the museum collections a precious mine of information and inspiration.

Gordon Walters in his Christchurch studio

(photograph by Marti Friedlander)

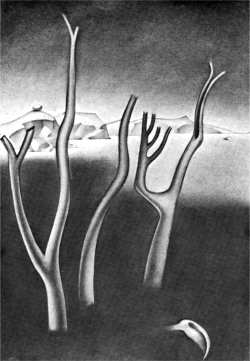

In 1936, Walters began classes at the Wellington Technical College School of Art. In his early representational works he painted still-life pictures, knowing he had an audience and even a small market for his efforts. With the war came changes. For a time there was an influx of refugees: among them people knowledgeable about recent European art. One such was Theo Schoon, a Dutch-born Indonesian artist, whom Walters first met in 1941. It was the start of a long friendship. By discussing ideas outside the narrow Art School range with Schoon he gained the " stimulus to take new artistic directions leading to his discovery of Surrealism. He made a striking series of conte drawings, with the striations, mysterious shadows, and deep space planes familiarized by the French master, Yves Tanguy. By using local imagery, choosing bare beaches, dead trees, sand dunes and stones he evoked visions of New Zealand as a depopulated wasteland existing on the edge of the charted globe. From afar, the Surrealists had given New Zealand some prominence on their world map as a strange, remote country. At close range, Walters gave substance to their speculative dreams by including such things as a giant ovoid stone, like a petrified moa's egg, a vestige of some former presence in the now empty landscape. There are, too, surprising, almost shocking drawings full of erotic imagery: close to the spirit of European Surrealism, but in sharp contrast to New Zealand art of the time, where any suggestion of sex is hard to find. Those were the days, Schoon used to say, when the one painting of a nude on show in a public art gallery was veiled by a curtain. It could be drawn only by request and at the viewer's risk.

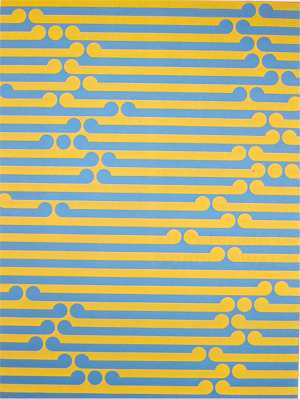

GORDON WALTERS

Blue and Yellow c1967

acrylic on canvas, 1375 x 1830 mm.

Surrealism was a passing interest for Walters, who went on to experiment with a range of styles in the mid nineteen-forties. In particular, the work of Paul Klee helped to direct his painting towards an abbreviated language of line and symbols. Contributing to this development was his discovery of primitive art - a discovery that for him led out of Surrealism, as it had for artists like Miro, Pollock and Gottlieb. Walters looked at diverse cultural sources, and his drawings of that period include a study of a Benin bronze. Maori rock art emerges in 1947 as a strong influence. That year he visited Theo Schoon, then in South Canterbury where he was making copies of rock drawings for the Department of Internal Affairs. Like Schoon, Walters was impressed by the rock artists' economy of means.

In his Drawing of 1947 the effect of these ideas can be seen clearly. Walters drew the simplified figure in one tone on white paper, rather as the New Zealand rock artists placed their drawings on limestone bluffs. It is a radical departure for Walters and for New Zealand art. Now the white paper is both the field and also an integral part of the drawing. At the head and extremities, the open spaces between the lines allow the paper to become white bars that repeat and echo the black drawn ones. There is the beginning of the figure/ground ambiguity so Important for the artist's later, better-known works. He no longer based the figure on anything he had seen: it is an artistic invention. He carries on the conceptual basis for his imagery in related works, such as The Poet, of the same year.

GORDON WALTERS

Untitled gouache 1955

209 x 279 mm.

(collection of the Auckland

City Art Gallery)

By this fundamental change, Walters made his art stylistically compatible with what he admired in Polynesian and Micronesian works. This enabled him to bypass the illustrative approach to the use of Maori and Pacific motifs, so typical of earlier New Zealand work, and to achieve a degree of assimilation. These 1947 works - revolutionary by New Zealand standards - incorporate ideas often mistakenly thought to develop only in Walters' paintings of the 'sixties. Instead, the starting point lies two decades earlier.

1947 was the year, too, when the artist first left New Zealand to spend fourteen months in Australia. After his return in 1949, he made the mistake of exhibiting his new work in the Wellington Library. From the hostile reception he learned the hard way how unacceptable his work was to local critics. Realizing this, he left for Europe in 1959. He spent over a year in Europe absorbing at first hand the paintings of modern masters such as Mondrian, Van der Leck, Arp and Klee. In addition to these, contemporary French non-figurative artists, such as Auguste Herbin and Victor Vasarely, made the Denise Rene gallery in Paris a favourite haunt. The strict geometric abstraction of Herbin, for example, with the emphasis on hard-edge surface shapes, finds many echoes in the gouaches Walters made in the years following.

GORDON WALTERS

Waikanai Landscape 1944-45

conté crayon, 599 x 380 mm.

By late 1953, Walters was back in New Zealand - at first working in Auckland, then in Wellington. Here we confront one of the puzzles of his career. Why was he reluctant to exhibit his works during the 'fifties and early 'sixties? It was not because he was doing few paintings: this was in fact, a period of enormous creativity. Some reasons are easy to find. He thought that the critical situation was no better than before, and just as useless for his purposes. Also, being self-critical, he did not want to exhibit experimental works. Besides, he was looking afresh at Maori and primitive art sources. Further, it was a period of intensive study, of experimentation, of occasional triumphs, of some artistic dead-ends. The paintings tell their part of the story.

What Walters was doing involved testing a range of ideas: some derived from primitive art, some from European abstraction. It is not easy to talk about these works because none were exhibited and few have titles. He began using variations on a limited range of motifs with simple geometric building blocks such as squares, rectangles, circles and chevrons. Some of these are highly coloured, perhaps under the influence of the School of Paris abstractionists. The colours in others are flat and strictly two dimensional, causing a degree of optical interaction which gives added surface movement.

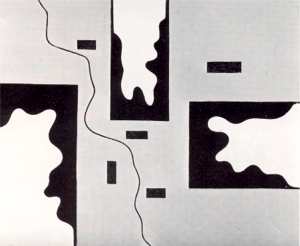

GORDON WALTERS

Abstract Painting 1955

oil on canvas 511 x 610 mm.

Walters' Abstract Painting, 1955, is one of the rare oils of this period. It gives a good idea of his grasp of picture construction based on a few forms. The rectangle is important here. Starting with the shape of the canvas we discover the family likeness between the large and small elements encroaching on it. The line wandering through the picture from top to bottom provides a contrast with the colour blocks as well as a way of traversing the picture with the eye. It shows how Walters arrived at the white shapes by filling in one side of the lines with black. Seen in relationship to the straight edges, both black and white shapes can alternate as positive and negative, depending on the perceptual process. Walters starts to shift part of the action to the mind of the viewer. How we understand it very much influences how we see such a work.

GORDON WALTERS

Untitled Ink Drawing 1956

At what stage did Walters isolate the 'koru' motif for special attention? That is rather hard to pinpoint. Certainly in 1956 he made several small works on paper in which the 'koru' is set out horizontally and simplified. But the ends curve organically as in Maori art, and the motif is not fully absorbed into a frame-work of geometric elements. Triangles and circles mingle somewhat uneasily with the hand-drawn 'koru' bulbs as they struggle to accept the imposed order. As yet the 'koru' motif is one of a number of Polynesian and Micronesian designs Walters incorporated into his art at that time, and not the dominant one. In fact, a stylised totemic figure to be seen in some recent paintings, appears to have attracted more of the artist's attention. From a gradual process of trial and error, and out of the realisation that there was no need constantly to invent new forms, he isolated a severely geometric version of the 'koru' as a personal signature theme.

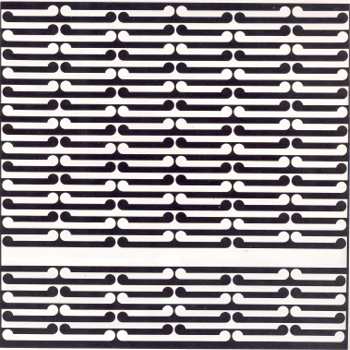

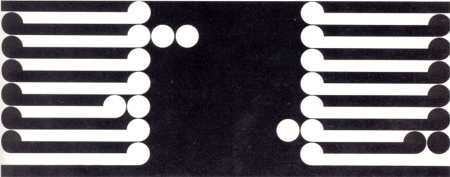

Perfecting that motif took some eight years of dedicated labour. In.-its final form, as seen in works from the first New Vision show of 1966, it is incredibly simple - so right that it seems obvious and inevitable. The free-flowing, hand-drawn 'koru' becomes a straight band of tone, its 'bulb' a circle. Now the incorporation of circles, as in Painting No.8 1965, appears perfectly consistent and part of the same geometric alphabet. So, too, do the bands and blocks of colours. The interplay of positive and negative is stated unequivocally through the restricted range of formal elements. Unlike Maori 'koru' patterns, positive and negative are identical in shape in Walters' works so that our perception of their relationship is immediate and insistent. Also, the much greater sharpness and precision of the shapes, compared with Maori painting, move Walters' imagery away from the associations of a hand-made artefact to those of a machine-made product from the primitive to the modern cultural context.

GORDON WALTERS

Painting No 8 1965

acrylic on hardboard, 1220 x 915 mm.

Already in the 1966 show Walters suggested the wide range of possibilities available within the 'koru' motif. Because he spent years making studies on paper before committing himself to canvas it, often happens that the date of a painting tells us little about the time it was first conceived. For example, Painting No.8 1965 - unusual in the retention of red ochre, black and white, colours closely associated with Maori art - shows on the right-hand side the vertical stacking of , elements he returned to later in the Genealogy series. This picture is relatively stable, and free from the dazzle and after-images associated with the well-known Painting No.1 1965, in the Auckland City Art Gallery, where the bars of black and white are narrower and more numerous. There the rapid movement of the eye from black to white reading seems to be quite unlike the slower pace required by Painting No.8 which was in the same show. Normal stylistic criteria do not seem to apply very well when each painting is engineered to be distinct from another.

Walters described his aims at the time as follows: My work is an investigation of positive/negative relationships within a deliberately limited range of forms; the forms I use have no descriptive value in themselves and are used solely to demonstrate relations. I believe that dynamic relations are most clearly expressed by the repetition of a few simple elements.

GORDON WALTERS

Genealogy 1974

acrylic on canvas, 1523 x 1523 mm.

While there is no mention of a specific interest in the effects achieved by contemporary European 'Op' artists; it is tempting to draw some parallels. like, many 'Op' artists, such as Bridget Riley, Walters prefers black and white to colour. Black and white has the advantage of giving maximum contrast; it is dynamic, and most optical effects are readily achieved with it. The hard-edge quality of Walters' painting, too, gives the crisp definition of form basic to much 'Op' art. In the insistent beat of the 'koru' motif, as in Genealogy 1974, there is the repetition of geometric shapes so essential in the periodic structures of 'Op'. Certainly, many of Walters' paintings have side-effects identical with those of European 'Op' art. These include dazzle, after images, traces of colour, and suggestion of movement or shimmer. In coloured works, such as Blue and Yellow, 1967, because we are forced to view the colours simultaneously, we get traces of their complementaries and a range of perceptual effects seemingly happening in front of the picture plane.

During the twelve years since the first New Vision exhibition, Walters has shown the wide range of compositions possible within his 'deliberately limited range of forms'. Instead of being limited, he has been forced to find new solutions for each picture. At times he has worked with severe economy, deploying only a few motifs on the perimeter of a square or rectangle; he has massed whole armies of motifs one above another in his Genealogy series; or he has allowed flowing, almost lyrical dispositions, as in Blue and Yellow, where they move up and down the canvas as if in rhythm with some unheard music. Harsh juxtapositions of black and white contrast with a muted delicacy of tone and colour in a work like Rapa 1971. Without seeing a representative group of these remarkable works together it is hard to visualize how they comment on one another. But one thing seems certain: collectively they form one of the most important groups of paintings made in this country since the war.

GORDON WALTERS

Oreka 1976

acrylic on canvas, 2440 x 950 mm.

1. The articles on Walters are few, but valuable. These are:

Hutchings, P. 'The Hard Edge Abstractions of Gordon Walters', Ascent, Vol. I, (4), 1969, pp. 5-15.

Hutchings, P. Eight New Zealand Abstract Painters', Art International, Volume XIX, (1), 1975, pp.18-27, 32-35.

Vuletic, P.L. 'Gordon Walters: Origins of a Style', Artis, Vol. 1(2) 1971, 12-14.