The Eye of an Outsider:

A Conversation with Ans Westra

Ans Westra is one of the premier photographers in Aotearoa, and her almost 40-year-long engagement with the representation of Maori culture is a substantial addition to cross-cultural visual culture in the twentieth century. Washday at the Pa, which created some controversy when it was first published in 1964, has ensured her work sits directly at the centre of debates around Pakeha representation of Maori. Damian Skinner recent spoke with Westra in Wellington, where she currently lives; the conversation began with a question about when Ans' interest in photography began:

ANS WESTRA: As a teenager I had a stepfather who owned a Leica camera, and he had taken a lot of photographs. That exposed me to photography. We went to see the Family of Man exhibition which made a big impression on me - the enjoyment, the variety of people. I also found I had an affinity with photography, I could express more with it than with anything else. I tried to carry on with drawing, because I had attended a craft course in Holland. We did a lot of drawing, but photography was really what I could say the most with, so I pursued it. And when I came to New Zealand in 1957, I felt I wanted to do a book on the Maori.

Two early issues of Te Ao Hou, featuring cover images by Ans Westra

DAMIAN SKINNER: Were you professionally trained in photography? A.W.: No. I taught myself. When I looked for courses in Holland there weren't any in photography at that time. When I went back in 1965, they'd started photography courses but I was already too far ahead and didn't want to go back to school. D.S.: What was your first paid job as a photographer? A.W.: I just started working freelance. I did work in a camera shop when I first came to New Zealand, which had a studio attached as well as selling cameras. But as for selling my own photographs, I started to work freelance. I sold some to the magazine Te Ao Hou, then to the Education Department. I didn't actually ever work as a photographer in paid employment.

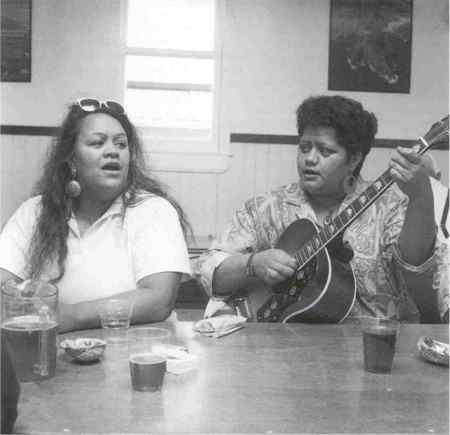

ANS WESTRA Nukualofa, Tonga 1962 Black-and-white photograph

D.S.: What outlets existed for photography during this period? A.W.: There weren't very many magazines. I did sell some articles to the Weekly News for instance, and also some whole page photographic sequences to various newspapers, so they did look at some outside work. But there weren't nearly as many magazines, not as much variety as we have now. That's all come since. I had taken some photos of the Maori when I was hitchhiking around and I showed these to Te Ao Hou and they bought a couple of cover pictures. Those were the very first published photographs. D.S.: Tell me about this hitchhiking journey that you went on. A.W.: Oh, I just travelled around. The Te Ao Hou pictures were taken in Rotorua. I was just trying to see more of the country. Eventually I thought I would be better off having a car, so I stayed in paid employment until I could afford a car. I wanted to have more freedom. I slept in the car and moved about with it. Initially it was just hitchhiking, coming to some grief. [Laughs]

ANS WESTRA Turangawaewae, Ngaruawahia 1963 Black-and-white photograph

D.S.: What did you think of the state of photography in this country? A.W.: Well I also joined the Camera Club as a kind of instructional thing. There wasn't a lot of real documentation being done. The books that came out on the Maori were very much aimed at the tourist market-very, very formal and posed. So my pictures were more natural ones and stood out that way. I was wanting to observe life as it happened, without interrupting it as much as possible. D.S.: When did you first begin to sell photographic prints as opposed to photographs for publication? A.W.: We started looking at photography as exhibition prints in the early 1970s, really. We had our first exhibition in a dealer gallery with the Barry Lett Galleries in Auckland. It was a group show. I can't remember who else exhibited-probably John Fields, and some of the Auckland photographers. I think this was the first time Barry Lett showed photography in his gallery.

ANS WESTRA Koriniti, Whanganui River, 1990 Black-and-white photograph

D.S.: How did people respond? A.W.: Well, we didn't sell anything, it wasn't the best beginning. [Laughs] Actually, it was very much a question of whether photography was art, or was acceptable as art. D.S.: Where was your first public gallery exhibition? A.W.: I had an early show in the Dowse Art Museum, a retrospective. That was probably one of the first. When Photo Forum started, they had a gallery and we held exhibitions there. Gradually photography got into the public galleries. D.S.: Has exhibiting photographs rather than publishing them affected your artistic practice? A.W.: No, not really. I don't photograph to make pretty pictures as such. No, it still is very much the documentary style.

ANS WESTRA 'Washday at the Pa', Ruatoria 1964 Black-and-white photograph

D.S.: Tell me about the process of working with Te Ao Hou and School Publications. A.W.: Well, Te Ao Hou would tell me where things were happening and specific people they wanted to have an interview with. So sometimes I would write it, and sometimes the magazine's editor Margaret Orbell would write it and I would just take the photographs. They would come up with the topics and get me to go to things on their behalf, and it gave me an introduction to various places. They didn't really employ me, they just paid me for the work they published, which more or less covered expenses. It gave me the material because I had already the idea of doing a book about Maori, and I was keeping all the copyrights. It was a mutually beneficial arrangement. Te Ao Hou couldn't afford anyone to go on the road and be fully paid. They were working on a very small budget. D.S.: And what about School Publications? A.W.: I was going to go to the Pacific and they were looking for stories around the life of children in different situations. They said to look out for something there and I did Viliami of the Friendly Islands. That was really my very first published book. They gave me some guidelines about what they wanted-how big a story, with a beginning, middle and end-and I went and looked for it.

ANS WESTRA 'Washday' Revisited, Napier 1998 Black-and-white photograph

D.S.: How did you first make contact with them? A.W.: I had won some cups at the Camera Club and the newspaper did an interview and published the pictures. In the interview I said that I was planning to travel to the Pacific, and I was planning to do a book on the Maori. So School Publications said to do something for them on that journey to the Pacific, and Reeds asked if they could publish the book on the Maori. It was very useful-I immediately had the two contacts I needed. D.S.: When did you start to get a sense of what other photographers were doing in New Zealand? A.W.: Well it was really when Photo Forum started that we got more of an awareness of what other people were doing, what was out there. But that was when I came back to New Zealand in 1970. I went back to Holland in 1965 and I tried to get into photography there, but it had sort of all moved on. It was part of the established art scene there. D.S.: What do you mean 'moved on'? A.W.: Well I didn't . . . I put in some work for a competition. It was called PhotoPrize Amsterdam, and it was for young photographers just starting out. They were much more trendy than me. My photographs were just too straight.

ANS WESTRA 'Washday' Revisited, Te Puke 1998 Black-and-white photograph

D.S.: Do you think that difference in your photography emerged from being in New Zealand and the developments in the local culture? A.W.: It could be that it was just because I'd developed my own style here. I found what I could do best. So I didn't really find my way again in Holland, probably because I'd started off here, been too far away from it. D.S.: When you worked for School Publications, how much control did you have? A.W.: It had to fit very much into their formula, with what they wanted. There was a variety because sometimes I submitted things-like with Washday at the Pa, I did my own thing totally. And sometimes I was given a story to illustrate. My photographs would have to fit in with the story line, to follow it. D.S.: Can you give me an example of that second scenario you've outlined? A.W.: I'm thinking more of later examples actually, where there was a developed story line-perhaps a Maori text-of something that was happening and then we had to go and act it out. There was one which was called Lost and Found, the children getting lost and found by the Police, so they had to go through the whole story and act it out. There wasn't so much freedom there really.

ANS WESTRA Ratana Church, Te Hapua 1991 Black-and-white photograph

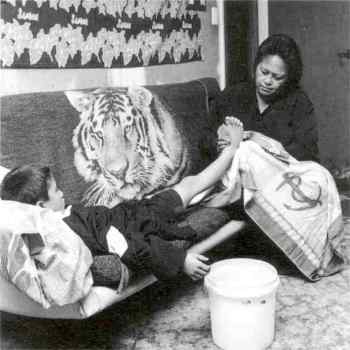

D.S.: Tell me about the process of putting Washday at the Pa together. A.W.: I knew what kind of story they wanted and I happened to come across this family that looked very picturesque, and I took the photos and took them home, wrote the story and then just presented it as a total thing. And they didn't change much except they added one photo of the house the family was meant to be moving into, the Maori Affairs house, because they felt that the house that they were living in was sub-standard conditions and it could offend the Maori. But the story explained that they didn't do anything to the house because they were moving out and into a Maori Affairs house. Which was happening. At the time the book was published, the family had moved into Gisborne. But yes, I made up the whole story line and School Publications changed very little, my text was used. D.S.: Who did you present it to? A.W.: All of the people working at School Publications gathered over it. John Melser was the person I was working with most. He was the head of School Publications.

ANS WESTRA Te Hapua 1990 Black-and-white photograph

ANS WESTRA Te Hapua 1990 Black-and-white photograph

ANS WESTRA Kaitaia 1990 Black-and-white photograph

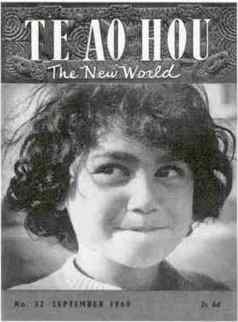

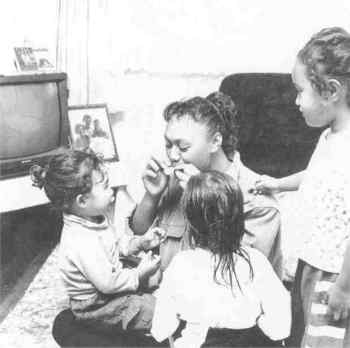

D.S.: How did the process of permission develop and take place with the most recent photographs? A.W.: I went to ask them each time, and also I had got some money to give them for being photographed, so they got a fee. I did get some Arts Council money for that. I calculated in a fee for the family. I went to ask first and then came back and photographed the next day. They were all quite happy. They got copies of the photographs as well. D.S.: Did you find any differences in attitude towards being photographed? A.W.: No, they were totally the same. They were really tuned in to how I wanted to work, and it was a very simple process. D.S.: Did you have a story in mind when you were taking the most recent photographs? A.W.: Not so much, not such a strong line. No, because I actually visited three different families, there were eight children so there were quite a number to choose from. I haven't got a direct story line. It was really comparing the situation now with then. D.S.: Why did you begin to photograph Maori? A.W.: It was the most interesting thing here, really. My neighbours in Glen Eden, in Auckland, were a big Maori family and they were so lively. Maori were wonderful to photograph because they're just spontaneous and natural, just the most colourful and interesting thing in this country at the time. D.S.: So that family were the first Maori people that you photographed? A.W.: No I didn't photograph them, I just observed them. [Laughs] They seemed to be the most interesting thing here, and also there was this strong feeling that things were going to change, that here was something historical that needed recording. They were moving from the countryside into the cities. There was this sort of falling apart of tribal life at the time and Maori were losing their identity a bit. The feeling at the time was very strong that they should become Europeans and be able to compete in society. D.S.: What did you think of photography featuring Maori at the time? A.W.: I didn't really see much, except for the more formal, the tourist style photographs. And we weren't really aware either of the historical photographs that were taken-such as the Burton Brothers. It all came rather later. D.S.: Were there any other publications apart from tourist ones? A.W.: Gregory Riethmaier had published Rebecca and the Maoris. It seemed to be a little patronising. There wasn't much else. Reeds were going around doing the Maori in Colour. D.S.: You wanted to do a book about Maori. What did you have in mind? A.W.: I was just gathering material all the time for a while and I looked for somebody to write an introduction to it. That ended up being James Ritchie. I based the sequencing of my pictures on the Family of Man exhibition. I would collect a whole lot of pictures together and see what would work. I did most of my own layout from that. D.S.: Did the notion that the culture was changing affect the way you photographed Maori people? A.W.: I was just trying to record the hui, the tangi, what was still happening. Well, I've got some photos of people moving into town, documenting the social change that was taking place. D.S.: How did Maori respond to your photographing them during the 1960s? A.W.: The Maori would often say they couldn't visualise that any of their people would work in this kind of isolation because I had to very much stay on the outside and be uninvolved to get my pictures. They said, 'We couldn't visualise a Maori girl doing this because it's too lonely'. When the photos came out in Te Ao Hou, they seemed to stand out. Maori enjoyed seeing them, seeing the warmth of them. They seemed to feel that I was sympathetic towards them, I was trying to learn about them, always had a positive response. D.S.: Did that change after some of the debate around Washday at the Pa? A.W.: Yeah, there was more questioning of why an outsider should be doing this. But again, that feeling that perhaps a Maori person would get more caught up in the politics and wouldn't be able to work in such isolation, I had quite a special place there. D.S.: You mentioned that your work with Te Ao Hou gave you an introduction to cultural situations. Obviously that must have facilitated your ability to work in a particular time and place? A.W.: Yes, it helped to be part of that and to be doing the photos for them in the first place. D.S.: Did you have any bad experiences? A.W.: Not in the 60s, except the whole thing with Washday. That came as quite a shock actually. D.S.: When would you say that the climate changed? A.W.: Well, with the new Maori intelligensia coming through, beginning to question whether they should have the right of presenting themselves. More in the 1970s they began to query. D.S.: How did that affect you? A.W.: Well, I began to photograph a variety of nationalities in New Zealand, just look at people in general. But yes, you were being questioned whether you were the right one to be the recorder, along the lines of 'you haven't got a Maori mind'. They would confront you, they would query whether you had the right to be doing this, and the other feeling that you were actually exploiting them. They were providing the entertainment and you were selling the images. D.S.: In the 70s, were you photographing Maori for specific publications or purposes? A.W.: No, I just carried on photographing for myself. D.S.: Do you think that made a difference to the way people responded? A.W.: Well, yes I didn't have a magazine behind me any more, so that made a difference. D.S.: How does your being Dutch affect these interactions? A.W.: Well often they would tell me that a member of their family had married a Dutchman. It helped a bit because there was quite a lot of intermarriage between the Dutch and Maori. It perhaps was easier to be Dutch than anything else. D.S.: Do you think being Dutch affected what you saw when you looked at New Zealand culture, and specifically looked at Maori culture? A.W.: Yes, well I was certainly thinking that the Maori culture was the most interesting element here, the most lively, the most authentic really. But perhaps coming from Holland, where we had an interest in the Indonesian people, this might have had something to do with it. D.S.: What's your view of the arguments around representation and the appropriateness of someone like yourself, who isn't Maori, taking photographs of Maori? A.W.: I can understand where they are coming from, their questioning it. Why I am the one who has the validity to document them. I find that being an outsider gives you a clearer vision, but I can understand that questioning of whether my approach the right one. D.S.: Do you think your approach has changed in response to any of these criticisms or a changing cultural climate? A.W.: Well I've got a bit firmer in what I'm saying, I think, more definite. I know what I'm going for. Just having been around, I'm a little bit surer of myself now perhaps. D.S.: What are your intentions when you photograph Maori? A.W.: Just an understanding really, I try to learn who they are, what they are. I try to get to know and learn about them. I've always been doing that. I'm trying through the process of photographing to get to the essence of what they are about, who they are, getting to know them really. I just have a curiosity about people that come from a different background. D.S.: Do you think that it is necessary for the outsider position to be upheld in order to record another culture? A.W.: Well, I take my conclusions from it. Whether they are what the Maori want to have themselves presented by is questionable.