Replacing Women in Art History

CHERYLL SOTHERAN

. . . around 1970 women artists introduced an element of real emotion and autobiographical content to performance, body art, video and artists' books . . . they have brought over into high art the use of 'low' traditional art forms . . . they have changed the face of central imagery and pattern-painting, of layering fragmentation and collage . . . but these are simply surface phenomena. Feminism's major contribution has been too complex, subversive and fundamentally political to lend itself to internecine, hand-to-hand stylistic combat.

LUCY LIPPARD, Sweeping exchanges: the contribution of Feminism to the Art of the 1970s (Art Journal, Fall/Winter 1980)

a gallery . . . that is so determined to show art that serves its own polemical ends has less to do with art than it has with politics and a form of therapy for disgruntled ladies . . . There is no such thing as 'women's art', or 'men's' art - there is just art which remains, in my definition, the ultimate expression of the individual regardless of sex or political persuasion.

NEIL ROWE, review of women's Gallery (Wellington) show (Evening Post Feb 2. 1980)

'Internecine stylistic combat' indeed .... It is characteristic of New Zealand art writing, however, that Rowe's, rather than Lippard's view seems to be the more accurate description of art by women in this country. What is provided in the present issue of Art New Zealand is a chance to assess whether this is a distortion by New Zealand critics and writers, or the truth about what women artists here produce, and their reasons for producing it.

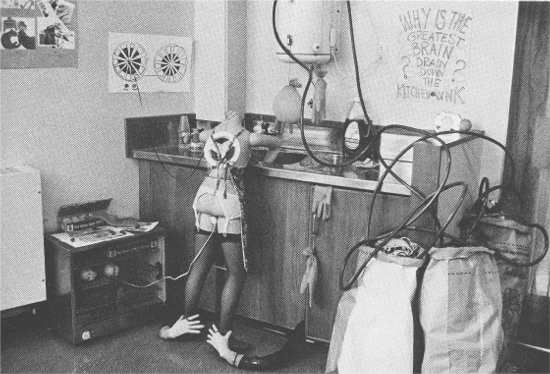

Women's Art Environment?

(Photograph by Gil Hanly)

Neil Rowe's stance is that of a 'modernist' male art critic, insisting on the universality of an art in which gender could be of no more significance than race or creed. His insistence that separate development as described by Lucy Lippard is not nurturing, but destructive, superficially connects with the resistance to identification by gender seen in the works and comments of many women artists in early twentieth century New Zealand - some of whom are discussed in this issue. And that this is the prevailing tradition in women's art in this country seems to be supported to the present day by the fact that most critics in New Zealand avoid or condemn exhibitions of women's art which use gender difference as a political weapon. The women whose art receives favourable reviews (or in many cases any reviews at all) are those whose work fits the modernist mould, are not feminists, are asexual and apolitical.

In fact, and contrary to the impression derived from the bulk of New Zealand art writing, there is a great difference in political attitude between those earlier artists and many women working in the arts now. Neil Rowe's rejection of the rich diversity, content emphasis, argumentative, contentious committed qualities not only of women's art but of post-modern art, in general distorts the contribution made by women to the local art scene.

Meeting to discuss

Carole Shepheard's

Full Circle project

(Photograph by Gil Hanly)

Critical opinion has of course distorted women's contributions in other ways. Art in New Zealand (this magazine's predecessor in the 'thirties and 'forties) seems to give more coverage to women than this one does, even in the age of the Women's Art Movement. Reviews, reproductions, articles are prolific. Yet another sort of critical distortion diminished their role even as it advertised their contribution. The commentators at the time allowed their stereotyped views of artistic influence to disallow the innovatory aspect of artists like Rata Lovell-Smith and Rita Angus, Flora Scales - emphasising instead their subsidiary roles to artists like Perkins and Weeks.

It is in this area, although not in the area of the modernist versus feminist conflict, that the present issue of Art New Zealand provides a valuable corrective. Those earlier artists, who were also women, mostly saw success in terms of doing battle on male terms, on a male battlefield. They had courage, they did well, and they laid the ground work (consciously or not) for the women to follow. This issue is of great importance as a record of that struggle, because it reveals that the conflict was not, often, apparent at the time, but has emerged retrospectively: in the mergence of a specific and self-consciously female art in this country.

The Birth Tunnel Lifescape

Auckland Society of Arts, 1982

(Photograph by Gil Hanly)

This art is developing, and has become more distinctive, and more political even though official statements about local art still seem to be describing the earlier situation: the women who make it in critical terms are still the ones competing in a non-gender sense. It's hard to find reviews of work that incorporate ideas of collective making, use of traditional rather than 'high art' forms and images, personal and political references... like the Lifescape project at Auckland Society of Arts in 1982 which was either ignored, or treated to the same trivialising as Neil Rowe used for the Women's Gallery show. Shows by individual women are too often described or assessed in alien terms by critics whose modernist bias does not permit them to see women's art in realistic let alone sympathetic terms. Women artists themselves set up shows in which women who insist on non-gender, apolitical identification hang next to works by artists who insist as strongly on having a clear political content.

This issue of Art New Zealand by its very existence has taken a major step towards the redress of such confusion by affirming the separateness of women's art. It has many valuable precedents (single issues of periodicals like the Oxford Art Journal, Art News), and many of its articles do much (through the process known as 'replacing women in art history') to correct stereotyped attitudes to the innovatory and influential nature of women's art. Since the 1970's, however, the tendency in feminist writing has been to move away from this historical perspective - showing how women artists of the past have conformed to male standards, and have been overlooked because of cultural conditioning rather than artistic inadequacy. Now there is a questioning of those standards themselves. The end product of such questioning is the establishment of a 'new' and distinctive women's art, and a major factor in its success is seen by many women as a period of compulsory separatism. While separate issues of art magazines, like women's art exhibitions, can run the risk of being seen as token gestures - easily ignored or dismissed by critics - the fact that it begins to redress the balance by giving serious attention to the work of such feminist artists as Carole Shepheard far outweighs the risk. Its principal value probably lies however in its placing of the women artists of the early part of this century in New Zealand art history.

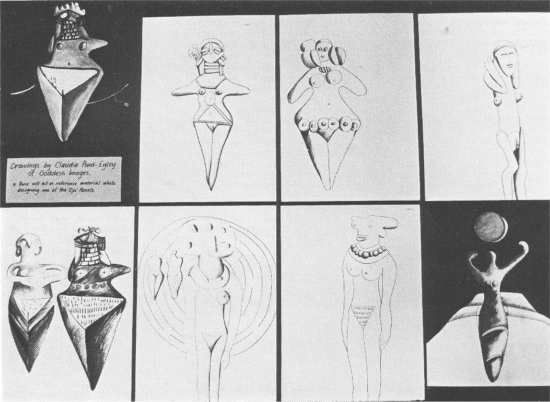

CLAUDIA POND EYLEY

Drawings of Goddess Images

(Photograph by Gil Hanly)

Lucy Lippard in 1976 said that 'clearly everyone looks forward to the time when distinctions between male and female are minimized in favour of a more human equality. But if women's art itself, whatever its 'quality', is indistinguishable from the art made by men that is already in the galleries, nothing will change.

In 1983, her dream of equality seems no closer, and the need to be distinctive in order to be effective still prevails.