Exhibitions Christchurch

MICHAEL THOMAS

The Robinson/Brooker Galleries

Robinson/Brooker Galleries, the new space for contemporary art, has opened in style. Situated in prestigious Hereford Street (which could soon become the Bond Street of Christchurch and even New Zealand), the large front window is designed to attract the eye of the business world.

Bruce Robinson, formerly exhibitions officer at the McDougall, has left nothing unconsidered from the visual point of view. A clean exhibition space of international standard has been created, with a Fifth Avenue 'feel'. His partner, Clive Brooker, a man of proven business acumen, provides the backing. It is a formidable combination, which has the makings of success in an area of need.

A professional service is to be provided for the artist and the public. The Gallery will act as agent for a small number of artists. Their work will not only be exhibited, but will also be actively promoted at home and abroad. Responsibility for publicity and sales will be taken over from the artist, who will be able to concentrate on the production of work. Private collectors, businesses, public corporations and galleries will also be provided with a professional service covering their needs. This will range from the supply of art works by New Zealand artists, to framing and matting, and a packaging and despatch service for works of art. An 'art safe' is being built in which members of the public can store their art works for specified periods.

Bruce Robinson's experience in public galleries has provided insight into both the needs of public collections and the expertise available. He plans to find the art pieces which the galleries require, and provide an authentication and valuation service using the expert advice available from throughout the country.

Exhibitions will last one month; and, apart from the current show, an adjacent space will house a display of stock. It is planned to build up this resource and to extend space for its exhibition to another premises already owned by Messrs Robinson/Brooker, presently containing art studios.

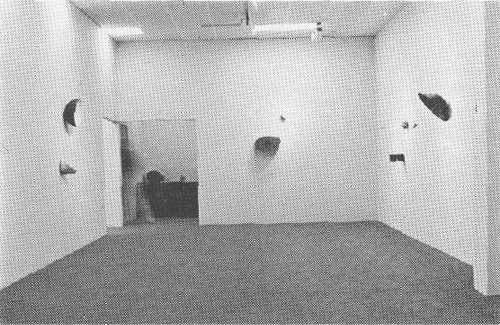

Neil Dawson is currently showing sculpture and photographs, and Paul Johns is exhibiting in June. Future exhibitions are soon to be finalised. It promises to bean exciting art season for Robinson/ Brooker Galleries, and to provide a shot of adrenalin in the Christchurch art scene.

Drawing into Painting, the show at the Robert McDougall Art Gallery of thirty-three paintings and fourteen preliminary drawings by realist Graham Sydney, is designed to provide insight into the artistic process. It succeeds in demonstrating that Sydney does not copy reality, but rather recreates an illusion of realism by observing, re-organising and editing. Selected works from 1975-1980 are shown; and alongside several pictures is a colour photograph of the subject taken recently by the artist.

Surprising aspects of Graham Sydney's interpretation of reality are brought out when his paintings are compared with the camera's relatively objective view of the facts. Sydney romanticises. Comparison between the photograph of Dogtrials Bar and Sydney's painting speaks for itself. The photo shows an ordinary shed which in the painting becomes an evocative relic capturing the atmosphere of a past era.

Sydney delights in exaggerating the eccentricities of standard building materials. The curled corners of corrugated iron, vein-like cracks in a concrete water tank, and old weatherboards, are rendered with particular attention to those parts where the natural process of decay has taken its earliest hold. Where this concern with the particular is subdued, as in Railway Red, the cohesion of the composition predominates and Sydney is at his best: here he elevates the mundane to the monumental. When the temptation to overemphasise detail for its own sake is not overcome, as in Weatherboards at Cluden, the work fails to cohere.

Light is well understood by the artist, and a feeling for its particular quality in each situation determines the tonal 'key' of individual paintings. In Dogtrials Room, Sydney controls tone sensitively to convey the gentle diffused light of the cabin's interior. Fog at Stan Cotter's is in total contrast to Huntaway Hut, where the light and sun of evening are strongly felt.

It is disappointing that Sydney does not seem to have sufficient feeling for mass and three dimensional space to augment his sensitivity to light. An impressive technique allows the artist to indicate distance with the conventional devices: but the water tanks and houses seem to have no weight; drapery fails in impossible folds; and things seem to hover against walls rather than lean upon them.

Several 'errors' in drawing arise from this apparent lack of understanding of forms in space. The elipses of cylinders are unconvincing (Charlie's Tank is the most blatant example). In Behind Stan's the chimney pots are out of true with the chimney stack; and the rim of the dustbin and water tank with its circular corrugations are badly drawn. A scarcely believable perspective is shown in the angle of the side of Dogtrials Bar, where a chair is seen with one side longer than the other. The spatial relationship between Limp Sock and its pole is ambiguous; and in For Hire it is not clear whether the top of the gable end of the roof recedes or remains vertical. Unusually bulbous and gravity - defying folds of drapery appear in clothing and curtains: as for example in Behind Stan's.

These little idiosyncracies of vision, however, are in a sense the most interesting thing about Graham Sydney's work. It may be that through them we see Sydney as he really is: unimpeded by the conventions of vision, if also unprotected by them.