Exhibitions Auckland

GORDON H. BROWN

Denys Watkins: 'Here and There', Paintings & Etchings

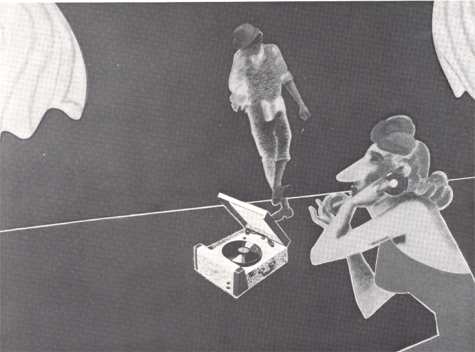

With Denys Watkins's recent exhibition it has become clear that the inclusion in his show two years ago of certain works in which one or two figures were set within a dark environment (see Art New Zealand 11: p 52) marked a change in the pictorial emphasis of his work as well as involving stylistic modifications. In the new paintings the figures and accompanying props are further isolated, so that they almost float within a neutralized background. In some works this ground retains its environmental implications: for instance the paintings Listening to the news or Science, or the etching I have enough money; while in other works this dark background colour, as in Peton, remains a ground against which the images function. In the former, the frontal stage format persists: as clearly demonstrated in Fire in my wire with its side curtains and performers; while something of the television screen can be seen in the etching Don't eat with your hands.

DENYS WATKINS

Fire in My Wire 1980

acrylic on paper, 570 x 760 mm

(Private Collection, Auckland)

Some works retain the artist's abstruse method of juggling a number of seemingly unrelated images into an intriguing pictorial composition. Key examples of this method are the painting Fallen Idols and the etching Maggie Papakura's education. The enigmatic quality of Watkins's work remains at its most puzzling in these works where the riddle of juxtapositioned images is at its most complex. This quality also resides in the seemingly natural image relationships found in Peron or Fire in my wire or combined with a casual wit as in Never cry Wolf.

The potent enigmas contained in Watkins's stock of images have been boosted by his trip to California and Mexico. In Cholula or Science the macabre Mexican associations have provided a new range of loaded images which fit easily into the evocative texture of Watkins's visual narrative technique.

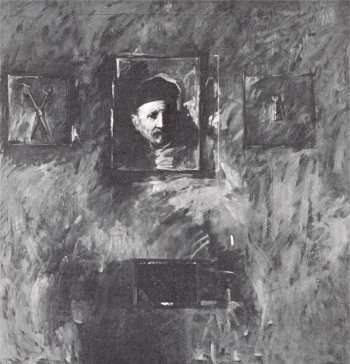

Ross Ritchie: New Works

It is at least four years since Ross Ritchie has shown a significant selection of his work. The six new paintings first exhibited in September incorporated aspects that have featured in his paintings since the middle of the 1960s, as well as extending such sources to include recent ideas. The lessons learnt from Larry Rivers, Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns early in his painting career have retained a hold of which Ritchie makes no secret. At their most obvious, the debt to this trio can be found in the imitation portrait of Rembrandt's father in Seam (The Fathers), the deliberate sweeping brush-strokes in Cot (Nurse) or the squeezed paint-tube and other objects in Three (Choice).

ROSS RITCHIE

Seam (The Fathers) 1979

oil on canvas, wooden box and coal,

1235 x 1235 x 100 mm.

(Peter Webb Galleries)

The paintings follow roughly the same layout: three isolated squares in the top-half of the canvas containing the painted images, with the 'real' objects placed in the bottom half and all these set against a fairly neutral but richly painted ground. Behind the combined painterly quotations, the imitation realism and the real objects, resides a conceptual basis that makes play on the one hand with the association of the various images contained within a single work, and on the other, with double meanings. In Hop (Red) the linking of these images appears simple, especially the left to right movement of the bird to its disintegration: but then the associations appear not quite so simple! The significance of each painting is hinted at in its title, but this remains only a clue as to how the images are to be linked by association. The dichotomies under-scoring the pairing off of the various elements are easily identified, as with the real objects opposed to the illusionistic ones: but the actual 'reading' of these can prove slippery. Such ambiguity, heightened by the 'realness' of the imagery, is further complicated by the very appeal of the painterly skills exhibited by the artist, a factor that also seems to work against the circumstances presented in each painting. Possibly, in painting them these works have been too well calculated.

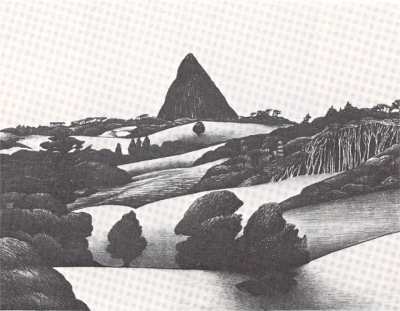

Don Binney: 'Points North': Paintings, Drawings & Graphics

In a critical sense Don Binney is not an easy artist with whom to come to terms. In the past he has established an ability to create evocative images that can carry symbolic overtones capable of linking the New Zealander to his environment. Conversely, as a painter Binney possesses certain 'blind-spots' that inhibit his ability to conceive his paintings with the visual clarity artistic unity requires from a successfully resolved painting. This applies particularly in his control of the tone values of one image in relation to another, so that pictorial ambiguity often results. What was pleasing about Binney's Points North exhibition was that the adverse effects of images spatially jumping out from their allocated position in the pictorial reality of a landscape were at a minimum. This resulted in the most substantial exhibition from Don Binney for some time.

The pictorial unity was strengthened by the common landscape motif that ran through the twenty-seven paintings, drawings and prints. The common source was the pointed volcanic plug formation known as Takatoka, and even when this sentinel feature failed to appear in two works, the landscape was geographically related, for the scenes depicted were in a direction away from the peak.

DON BINNEY

Maungaroha Point 1980

black and white lithograph,

810 x 1230 mm.

(Barry Lett Galleries)

As in the past, some of the most proficient works were among the drawings, notably Maungaroha Drawing II, Tikinui Northward I and the colour pencil drawing C.D. Friedrich: In Dankbarkeit, with its romantic indebtedness acknowledged in the title dedication. Possibly the most fully resolved work was the monochromatic lithograph Maungaroha Print '80.

If the paintings were less even in their artistic resolution, the best offered worthwhile rewards. The large canvas Tikinui Northward II possessed a broad rhythmic swell that overrode the few areas of weakness in its formal construction. By virtue of its simplicity the minimal images that made up Te Wahia, Westward, gained in both a pictorial and a technical sense, while in contrast the greater image complexity of the small version of Maungaroha From Te Maire II read reasonably well.

With his bird images, his colonial buildings, his Te Henga landscape, this steep volcanic cone also seems destined to become another 'Don Binney image'.

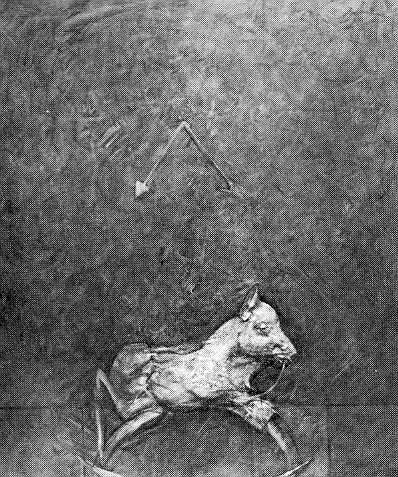

Alistair Nisbet-Smith: 'Specimens'

When first confronting the fourteen paintings in the Specimens series an impression of decay and disintegration dominates, as it does in much of Alistair Nisbet-Smith's work. If the overtones derived from Francis Bacon persist, they are less insistent than was the case with his earlier Heads.

In its design each painting has much the same disposition: a central 'living' object set on an exquisitely painted tawny-green ground. The edges of this ground, by stopping before the outer limits of the painting is reached, establish an artificial environment upon which the 'specimen' rests in isolation, and is projected with almost psychotic intensity at the spectator.

ALISTAIR NISBET-SMITH

Rocking Horse 1980

oil on canvas, 1220 x 1035 mm.

(Peter Webb Galleries)

In some paintings the unfortunate creatures appear to be the object of a messy operation. As specimens they twist and turn in an effort to sink into, or escape from the inspection platform and the disintegration that awaits them. What saves these partly metamorphosed creatures, with all their tortured flesh, from the grossness of morbidity is the neutralizing veneer applied by the artist to his handling of the subjects - the scrupulously painted surfaces that are so cool and deliberate in their artistic means.