Green Screen

Warwick Broadhead and Rubbings from a Live Man

ELIZABETH EASTMOND

When Florian Habicht’s Rubbings from a Live Man was launched in 2008 there was a standing ovation at a packed Civic Theatre, and at Waiheke’s little community cinema. I saw the film again last night 14 years on and seven years after Warwick’s death in 2015 in his Waiheke home. This time round, screened to coincide with this year’s Pride Festival, there were three people in the Waiheke Cinema auditorium.

MURRAY GRIMSDALE Warwick Broadhead c.2010

Acrylic on canvas, 760 x 1150 mm.

(Collection of William Dart)

I came away from that last screening thinking of masques and masks. I concluded that Rubbings from A Live Man (Warwick’s chosen and disturbing title), unlike his multitude of marvellous Dadaist, surrealist theatrical extravaganzas—his masques—was, quite deliberately, Warwick un-masked. Warwick in the raw. And what a paradox! All those mad, magical, events he had conjured up over decades were never recorded. That was Warwick’s dictum. They reside in our memories. Even some we never saw—I can vouch for that, having heard many descriptions of, for example, Warwick poised on a ladder, draperies billowing in the wind Warwick-like, in a performance at an opening of a Waiheke Sculpture on the Gulf exhibit. My gallery/bookstore Tivoli hosted three Warwick performances and, in the year before he died, one of his last renditions, by then a little shaky, of The Hunting of the Snark.

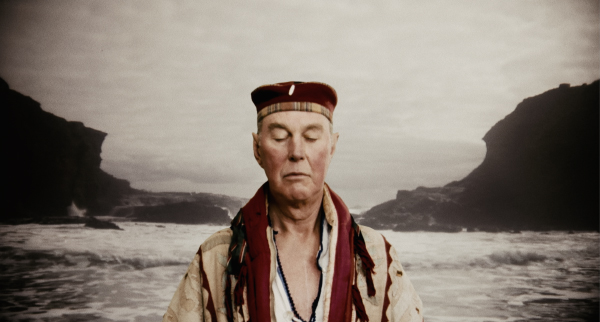

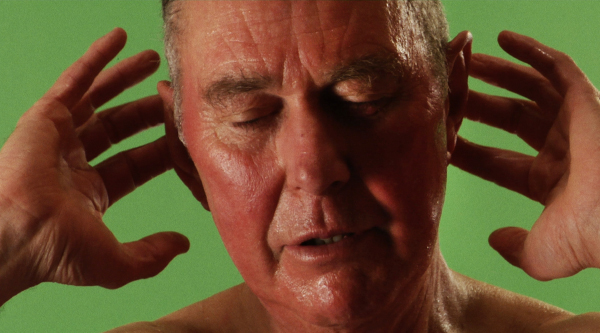

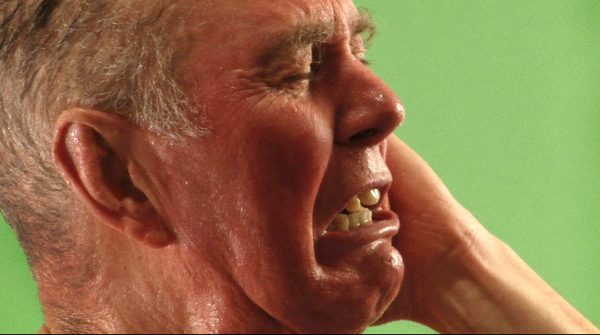

Above & below: Stills from Florian Habicht’s

Rubbings from a Live Man 2008

(Photographs: Christopher Pryor)

Warwick performed at some of the outdoor Pendragon Mall courtyard Poetry Festivals too. I remember him emerging like a turtle from a crocheted blanket on the ground, manically swinging a bucket of poems in flames next to the then i-Site Centre, dangling his leg over the balcony above in a failed attempt to swing down . . . Warwick as a vegetable at a protest at what is now the ‘Recycle’ Centre, Warwick wearing a waspishly wiggly 1940s man’s wig and causing consternation at a wedding . . . none of this and all the other extraordinary performances and interventions were photographed or filmed. No, Warwick wouldn’t have it. You couldn’t experience the beauty of the fleeting moment of creativity if you withdrew behind a lens. You couldn’t properly engage. No exceptions.

I liked that a lot. It was the antithesis of selfie culture. And highly unusual for most artists. His priority was the direct, transformative engagement of people, ordinary people, in creativity. For him recording not only distracted and diluted the experience, it made it something other, merely a lifeless artefact. Something referred to later, not truly experienced.

The result however: no part of the establishment canon. Plus the performances rarely took place in galleries, more often in other venues, from railway stations to beaches to private homes. Plus an everyday interaction, or, say, a meal, with Warwick could verge into theatre—where to draw the line between art and life?

So no going down in history, it seemed. No secure part in the history of New Zealand performance art. No making his mark as a creative involved in visual culture, via the conventional mode of photographic evidence.

But then what happened? He agreed to being in a film, a documentary. To being on screen. Lasting one hour and 34 minutes. Surely a contradiction. But the result proved, yet again, not only his radical perversity but his immense depths of creativity. Why? Because none of his older performances were re-enacted or discussed, no snippets including the Boojum from the Hunting of the Snark. Warwick and director Florian Habicht achieved a highly unusual result: a ‘documentary’ not about an artist, covering what they had done, but by the artist performing and talking about his own life including harrowing episodes from it. Talking it and performing it. Including his experience as a gay man. This was not material he had covered, as far as I know, or certainly not focused on, in his hundreds of theatrical pieces, even if their style was often highly camp. Yes this film called on the kinds of flamboyant props used in those performances, the wonderful bags on heads, plumed headgear, bizarre accessories, swathes of drapery, painted faces, feather boas (of course). But it was Warwick inside that was revealed in the film. Poor me. Poor me. Poor me, he said three times in the film. Some of his experiences were tragic. Whereas in the film his performance skills are demonstrated and he might pontifically, theatrically sprinkle a bunch of rugby players with flour, in that scene attention is also drawn to the fungus on his ageing toes. Whereas he might emerge incongruously from the leaves and dirt of the Symonds Street cemetery, his own preoccupation with death is obviously referred to. These episodes operate alongside the spirit expressed in him sadly pulling down his bodice to expose his skin, his chest. His personal pain, his ageing self.

Florian Habicht on the set of

Rubbings from a Live Man 2008

(Photograph: Frank Habicht)

This is also paradoxical in the sense that although ‘being himself’ in the film, this is Warwick in a film and the film becomes an artefact. It survives. To be referred to, enjoyed, later. Ensuring him a place in Aotearoa New Zealand’s pantheon of creatives. But, and very much but, the unique live performances, the very reason for the focus on the artist in the film, those projects that made Warwick’s contribution to creative life in this country so significant, these all remain elusive memories.

Still from Florian Habicht’s

Rubbings from a Live Man 2008

(Photograph: Frank Habicht)

I was struck, this time around as I was the first, by the shots of Warwick’s head. Such a remarkable head, and range of facial expressions. A myriad of diverse portraits. A couple of years before Florian Habicht’s film, I saw another unusual take on documentary on another charismatic figure: Algerian-born French football player Zinedine Zidane (Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait, directed by Philippe Parreno and Douglas Gordon).

Over 90 minutes of a game between Real Madrid and Villareal, 17 cameras tracked Zidane in real time. Mainly close-ups of his head, and, like Warwick, its immense range of expressions. Like Rubbings from a Live Man, this was another unconventional multi-portrait. Just as Rubbings from a Live Man’s focused on the performance of life in the film itself, not the subject’s earlier productions, neither were Zidane’s other sporting feats included.

I was also taken this time round by the shot later in the film of the lonely green screen. Screens feature as a motif, with those effective opening sequences of a screen set up at the beach, displaying ambiguous images, the sea behind. From time to time we also see the director himself, or the cinematographer at work, which, like the image of the green screen, are self-referential gestures making plain to the audience that this is a construct. This is a film being made. Here is Warwick in the now, both performing and being . . . himself. That green screen, the ubiquitous film- making tool, is not generally given such prominence as a kind of portrait of itself. There’s no one there in the shot. Warwick’s not there. Just the green screen: a device enabling you to depict disparate locations and sequences behind a protagonist. Like, say, a weather person. They can’t wear green of course, or they would disappear. Into the maps and the weather. Maybe Warwick was wearing green, then? Maybe he wanted to disappear, to wear a cloak of invisibility? But the focus on that cinematic tool, the camera lingering there for a moment, was poignant. Poignant in its pointing to the deconstruction of illusion, and in its allusion to emptiness. Much of the later part of the film has Warwick pondering death, and articulating his fear of it. The ultimate void. The green-screen shots later show turbulent waves crashing in towards us behind Warwick’s head rising up dramatically from below the cinema screen until his head dominates it. This captures the other side of that emptiness, of that void: the intensity of the subject’s interior life, his overflowing, overpowering emotions.

Going back to the very beginning of the film another particularly poignant image struck me. Perhaps it relates to the above: Warwick, as a pope, goddess or god-like figure cuddling, suckling and then burping a baby doll. It’s funny. It’s heart- warming. Then what does he do? He stuffs it, rather peremptorily, under the voluminous swathes of his costume. It’s gone, and we are on to the next take. Didn’t it suffocate? I was concerned! There was initially a celebration of life, nurture and love in that sequence. As he accords his family, despite the difficulties of his early family life. But there was also an abrupt disappearance, an abrupt ending. Although it was only a doll, a representation, you could imagine an extinguishing, a death. Warwick talks about the terrible impact on him of family deaths in the film. About a key relationship ending. About an unrequited search for true love. But nevertheless, despite such endings, life and the film go on.

Those hundreds of Warwick’s brilliant celebratory theatrical extravaganzas are different sides of, portraits of, Warwick. They salute joy and the imagination. They salute life. They honour the bizarre and the incongruous. Extend people’s sense of themselves and the world of creativity. They are not photographed or filmed. They are not recorded. They involved hundreds all over Aotearoa New Zealand and elsewhere—and, according to many, transformed their lives. They are lodged in many memories. Perhaps we should gather all these memories together to ensure at least their stories, their reimagining, if not their representation, is preserved. For a more complete portrait of Warwick. But would Warwick approve?

Rubbings from a Live Man can be streamed (for free) from www.florianhabicht.com