A View from the Inside:

The photographs of Catherine Russ

JANET BAYLY

The thing that's important to know is that you never know. You're always feeling your way. (1) These words of New York photographer Diane Arbus encapsulate Catherine Russ's attitude to photography. On her own journey of exploration, each image is a new discovery. Even if others have explored in similar places, Russ wants to go there for herself, and now she's on the road, she just wants to keep going. Now she's committed, its serious, she's 'hooked'. But it's not a commitment to any particular message about the world, in the usual tradition of social documentary, simply that she wants to show things how she sees them, and the results indicate an increasingly interesting journey.

Russ lives in Palmerston North which since the 1950s has produced many artists out of a strong network of high school art teachers, and the College of Education, Massey University environment. Currently she is photographing the insides of people's fridges, bedrooms, their verandahs and cars. It's a project on student flats in this town where the local economy and streets go very quiet over the summer break. Since 1993 she has produced a long list of locally-based projects, some commissioned or funded by grants, some self-generated. Solo exhibitions on Pork Chop hill, hair salons, and Clubs series have been presented at the Community Arts gallery and the Manawatu Art Gallery, while the Clubs series was also exhibited at New Zealand House in London in 1998.

CATHERINE RUSS Manawatu Outdoor Leisure Club 1996 Black-and-white photograph

Apart from a high proportion of students Palmerston North reputedly boasts more hair salons per head of population than any other New Zealand city, and a similarly high number of hobby and interest clubs. Russ photographed more than three dozen clubs in 1996, including Motorcycle Enthusiasts, Country Music, Bird Fanciers, Toy Dogs, Porcelain Dolls, Multiple Births and the Outdoor Leisure Club. Some were groups many of us would never gain an inside view of, raising issues of voyeurism which have existed since photography's inception, and engaged Russ more seriously than most.

In Outdoor Leisure Club, Palmerston North (1996) the caravan, wryly named 'Bare Inn', reminds me of Saskia Leek's mid-1999 installation at the Manawatu Art Gallery, Sleepy Hollow. Leek constructed a small, squat caravan out of cardboard in a darkened space and painted bright flowers around its sides. The effect was part fairy-tale, part-American comic-book, and part-New Zealand folk in its homely, '50s aesthetic. Closed eyelids over the windows and a nose and grinning mouth painted over the doorway created a self-satisfied, anthropomorphic presence. A similar, typically Kiwi, low-key sense of humour features in Russ's photograph. The name 'Bare Inn' and the down-home style of the caravan resonate ironically with the rear view of a well-manicured, well-proportioned but ageing nude woman, anxious to see the caravan's windows are clean. The setting is relentlessly bland and conventional, but the concern with appearances overlays a deeper sense of sterility. To make a filmic comparison, it's more Wim Wenders than Werner Herzog - any passion or hint of obsession has been ironed out. Many of Russ's images express a bleak sense of existential ennui similar to that of Mike Stevenson's early 1990s faux-naif paintings of Palmerston's down-home churches and famous clock-tower.

CATHERINE RUSS Saddle Up Country Music Club 1996 Black-and-white photograph

Saddle Up Country Music Club (1996) feels more emotionally loaded. A wide shot of a near empty hall shows two musicians on a distant, cluttered stage bearing a surprisingly elderly woman and a younger man engrossed in their instruments. They are being watched by a middle-aged seated woman whose ability to dance is somewhat hampered by being in a wheelchair. The Savage Club hall is a typically provincial setting, a place where people go for friendship and support. The kowhaiwhai painting and meeting house stage back-drop indicate its close links with Maoridom. But there is a melancholy sense of incongruity between disparate elements, and estrangement between people.

Russ's work is also fed by family connections to London, with her partner Simon hailing from there. She first went there in the mid-1980s aged 20, and ended up in the living room of Peter Turner, long-time editor of Creative Camera, Britain's most prestigious photography magazine, and took him on in intense, at times combative debates about the nature and politics of photography. Coming from a strongly woman-focused background, and deeply involved with feminist issues which were centre-stage here at the time here, it seemed to Russ that New Zealand had moved much further than Britain in its analysis of relations of power between photographers and their subjects, in both feminist and post-colonial contexts. Russ at first knew Turner as the partner of a relative, New Zealand-born fine art photographer and publisher Heather Forbes, and was quite oblivious at the time to his status as an internationally respected curator and critic of expressive photography.

Gradually she moved from the usual rejection of photography as being too easy, not real art, to an understanding that 'photography as an artform could be as simple or as complex as you wanted it to be'.(2) Significant in this process was a night class she attended in 1993 run by Kathryn McCool, a local woman who had recently returned to Palmerston after graduating from Elam. McCool was an inspiring role model both as an artist juggling motherhood and someone passionate about photographs as images, as art.

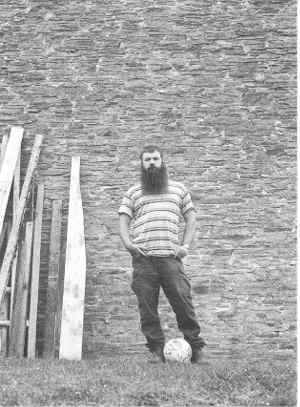

CATHERINE RUSS Simon, Cornwall 1996 Black-and-white photograph

A commitment to photographing in an ethical and non-exploitative manner, of 'not sneaking, taking or stealing' her photographs, has became an integral part of her practice. She is very conscious of that power of the camera of which Arbus has spoken, and which everyone, both the photographed and the photographer, is now aware. Russ needs to feel she can work as an 'insider' to get the kinds of images she wants. As a fly-on-the-wall observer or 'outsider', the more usual stance of social documentary or reportage photographers, she would feel uncomfortably intrusive or voyeuristic. She quotes British-born photographer Michael Kenna: 'The more respect, reverence and honour you give to whatever is in front of you, the better you will also be received'.(3)

Pork Chop is the popular name for a longtime hang-out on a bluff overlooking the flat lands of Palmerston North, where couples, hoons, teens and petty criminals have always gone. Visitors to the city are also brought here to admire the fabulous sunsets, older couples revisit the spot for sentimental reasons, and the cops regularly trawl through to check out the trouble-makers. In this scenario people are often slightly suspicious, withdrawn, assessing the risk of exposing themselves. Yet the 'Pork Chop' portraits are more directly engaged than the obliquely framed, formally aesthetic images of 'Salons' (see, for instance, Hamish of Champney Hairdressing Salon 1998). Shifting from black-and-white to colour has also heightened the tone and created an air of surreality.

CATHERINE RUSS Hamish of Champney Hair Dressing Salon 1998 Black-and-white photograph

A short quote ran with each of the 'Pork Chop' portraits, commenting on why the people had come there at that particular time. Russell was one of several whose response was somewhat vague, because it wasn't possible to talk publicly about it: 'It's a bit complicated eh, I can't really put it on tape . . . some heavy stuff'.(4) As an experiment the quotes were interesting for the sub-text they added, with all its gaps, although the whole project felt somehow awkward, reflecting the delicacy of the situation.

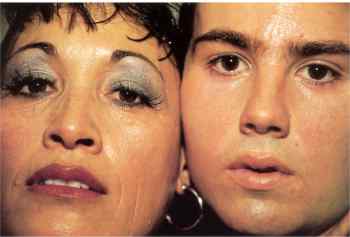

From the more conventional social distance of the 'Pork Chop' series, Russ went right into extreme close-ups for her series Shall we dance shown at PhotoSpace Gallery, Wellington in 1999, which really upped the ante. They were tougher images, edgier and hotter. Impressed by the commitment that competitive ballroom dancers had to their art, Russ decided she didn't want to photograph 'the dance' but the people themselves, focusing on the face. Shot on colour transparency with flash, the close-ups aren't particularly flattering or pretty. Tops of heads and chins are cropped off, so the viewer is wholly drawn into the subject's 'space', effectively inside their heads, almost impolitely close.

CATHERINE RUSS Pepsi and David 1999 Colour photograph

Self-display is an essential ingredient of ballroom dancing, but this is paradoxically subverted by something deeper and somehow unsettling which rises to the surface. Russ is not saying that these people are Other, but has conveyed their personal experience of other-ness in her photographs. Externally transformed by costume and make-up, on the dance floor they are also internally transported from their ordinary lives to an experience close to bliss. Their eyes convey an abstracted un-seeing, turned inwards.

An inner voice overrides the image's superficial stridency. It says, unequivocally, 'This is who I am, this is what I believe in, this is what I love, this is my deepest passion, this is my life', and that kind of statement is very arresting and moving. Yet there is no sense of voyeurism here, even though we are, in some sense, looking right inside these people's souls.

CATHERINE RUSS Russell 1999 Colour photograph

You could argue that Russ is simply investigating aspects of popular culture in the social environment. I think she is engaged on a tougher, more intimate journey than this, mapping new territories with the camera, negotiating what Arbus calls 'the endlessly seductive puzzle of sight'.(5)

1. Diane Arbus on archive tape in the video Diane Arbus, Masters of Photography series, Camera 3 Productions Inc. 1989. 2. Written communication with the artist, 14 April 2000. 3. Quoted in View Camera, November/December 1998. 4. From the 1999 Pork Chop series. 5. Quoted in Graham Clarke, The Photograph, Oxford History of Art, Oxford, OUP 1997, p. 28.