Kohia ko Taikaka Anake at the National Art Gallery

APIRANA TAYLORKohia ko Taikaka Anake is an exhibition of contemporary Maori Art—the largest exhibition to be mounted at the National Art Gallery since 1980, opening on 1 December 1990 and continuing until 17 March 1991. Kohia ko Taikaka Anake means 'gather only the heartwood' and Arnold Wilson's installation of tanalised posts and wood shavings is aptly placed at the entrance to the show. Perhaps one of the statements of this work is, 'Hey look, all the native timber is being hewed down and the result is industrial waste'.

The exhibition is like a deep and powerful journey and it's the awesome canvases and power of Selwyn Muni and his powerful painting that first grip the eye of the beholders as they enter the gallery. It's not just the political statement that makes these works significant in telling the true story of this country. The pieces themselves are beautiful to look at and the truths they reveal tell the artist's story against a background that is deeply Maori. That is, they start in Te Kore, the great void, and progress from the night into light.

Arnold Wilson speaking at the opening of the National Art Gallery's Kohia ko Taikaka Anake, in front of Selwyn Muru's Whakapapa (1990)

Further on into the exhibition and against a dark background, the bright colours and what to me are traditional kowhaiwhai patterns used by Sandy Adsett in his Tuhi series, are pulsatingly powerful especially if one is left alone with them.

As part of the exhibition there are ten iwi/regional groups who will install displays of their work. Each group's contribution will last from four to six weeks and the changeovers from one regional exhibit to the next will be staggered. The work from the Rotorua district and the people of Te Arawa affiliations offers a wide variety of experience to the seeking eye. For instance, in the photographs by Edward William Payton, the presence of a beautiful light is balanced with the darkness and shadows, and in these images the Maori sit or stand with pride and dignity and a feeling of closeness to the land.

This is indeed contemporary Maori art and in the bronze tekoteko by Lyonel Grant we are represented by a figure that radiates dignity whilst at the same time the viewer is moved to silent inner meditation and perhaps prayer.

Installation at the National Art Gallery's Kohia ko Taikaka Anake, showing (left to right, on rear wall) Bob Jahnke's Mana Whenua (1990), Jacob Scott's Titiro (1989) and Arnold Wilson's Apiti Hono (1990), with three Gateways by Ross Hemera in the centre (left to right), Taniwha Konutu (1990), Aotea Tomokanga (1990) and Ngohi Moana Riunga (1990)

At last I find the work of a woman in the exhibition, or rather three in a row. The first is a painting by Christine Reremoana Paul. It is from Whare Wahine series, and her figure on traditional patterns against a backdrop dark as the night, is larger than life. Mereana Hall uses bold, bright colours. This in itself is a statement. Colour for colour's sake? Yet there is much more. Perhaps one of my criticisms of the event is that there is so much to take in and so very little time to try and understand it all. Next to Hall's painting is one by Debbie Thyne. Her work makes a pleasing contrast to that of Hall, for Thyne has used quieter, earthier colours which prepare one for the myriad of figures and patterns the canvas. This could be too busy if it weren't for the fine balance of figures and soothing greens and browns used by the artist.

All the work in this section of the gallery deserves a mention, but that would require the writing of a novel to say it all. Let me say one word is worth a thousand pictures and perhaps a word for this whole exhibition is 'spiritual'.

One afternoon is not enough to take in all the work here. It is of such quality that it deserves at least two or three afternoons. How can I say it all? Perhaps I can best give an idea of the wide range of visions presented simply by giving the artist's names with their work. Ross Hemera's mountain He Maunga Tahuhu, Liz Sparks' Wharenui Arohanui, the great house of love and David John Burke's woodcuts of the coming together of Pakeha and Maori and the same artist's Separation of Rangi and Papa.

All the artists in this exhibition are tohunga. Their source is a traditional Maori culture and they've brought these values with them into the modern worId of contemporary art. Their art comes from a culture that is seeking and evolving and not one that to seeks to oppress, devolve and suppress. Kohia ko Taikaka Anake is worth going to see if only to be surrounded by the beautiful Maori colour so aptly used by the artists of a people who have such a fine understanding of colour and how to use it.

Installation at the National Art Gallery's Kohia ko Taikaka Anake showing, on the left, Emare Karaka's Waitangi Wailing Wall (1990) and, on the right, Buck Nin's Rongopai Experience (1973)

Buck Nin, in his painting Bird with Dancing Feathers, uses Maori or Polynesian patterns with his own blend of colour and layers, but the use of a different material for the bird's wing could indicate that Nin is developing into what for him may be new areas of creation.

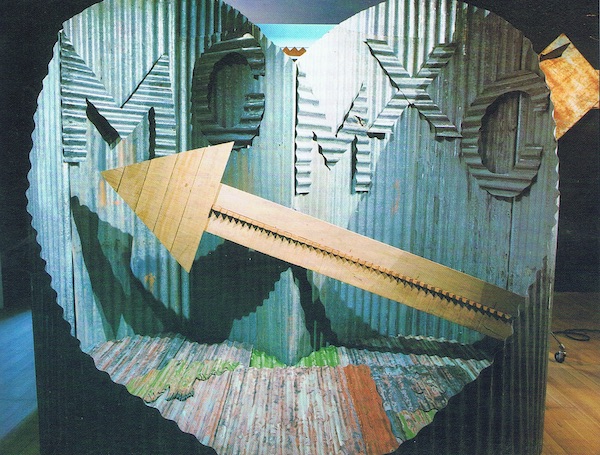

The exhibition could either begin or end with the work of Para Matchitt. His installation, wrought mainly of corrugated iron, reminds me of the kauta sheds and outhouses around the pa of my childhood, perhaps this is fitting since much of the work deals with the flag of Te Kooti.

PARA MATCHITT Te Ngakau MCMXC (1990) from the installation Nga Tohu no Te Wepu

Kohia ko Taikaka Anake is exciting, showing many artists developing in new directions. I know a little about traditional Maori carving and so the carving by Matahi Whakataka Brightwell, with its combination of Maori patterns and designs from other Polynesian islands, is both strange yet enlightening, as also are the paintings of Winifred Belcher, whose work contains many faces which are at first not seen.

HINERANGITOARIARI/WINIFRED BELCHER Nga Wha—The Flowering (1987-88) Acrylic on canvas, 1945 x 1520 mm.

Some artists withheld their work from the exhibition. It is sad that neither the organisers nor the artists could resolve their differences since it is we, the people, who have missed out. Mostly it is sad for the Maori people because most of us have been placed in such a terrible state of economic depression, that none of us will ever be able to buy these works and so therefore who gets them? The only way we can experience them is in an art gallery.

This is a positive exhibition for all. Those who miss it miss a lot.