Exhibitions Auckland

PRISCILLA PITTS Advance Australia Painting Neil Miller Maureen Lander

With NZXI now across the Tasman, it's interesting to compare that exhibition with a complementary project, Advance Australian Painting, which opened at the Auckland City Art Gallery in June. It's not quite a parallel exchange: Advance Australian Painting was curated, not by an Australian, but by Andrew Bogle of the Auckland gallery—in other words, from a New Zealander's viewpoint.

Despite its limitation (almost) to painting, Advance Australian Painting comes across as a more varied selection than NZXI. Nineteen artists are represented, with a greater diversity of styles and concerns than in the New Zealand show. There are the exquisitely detailed, vertigo-inducing sky and landscape images of 'naive' painter William Robinson as well as the dry-looking conceptual exercises of Peter Tyndall; the robust vulgarity of Susan Norrie's overlays of 'fine art' and popular culture imagery and the elegance of Stieg Persson's installation of small, near-abstract, densely black pencil drawings wreathed with glossy black plastic flowers.

This last work, like Paul Boston's papier mache wall-sculptures, is more than simply painting and, despite its title, the exhibition also encompasses four of Victor Meertens's richly-textured and subtly-coloured corrugated iron sculptures. (Meertens's letter to Bogle is one of the highlights of the catalogue and it's a pity his lively and illuminating talk at the gallery shortly after the opening of the exhibition wasn't better publicised and better attended.)

Two of Meertens's works have Maori titles — Korero and Karakia — happened upon by the artist while reading The Bone People. And there's even more of New Zealand in this exhibition; Imants Tillers's Hiatus combines copies of McCahon's Victory Over Death and von Guerard's Milford Sound (both in Australian galleries), fragmented into Tillers's characteristic multi-rectangle format. Tillers's use of pre-existing images along with his refusal of the unified and discrete 'work of art' bring into question certain concepts of authorship and identity; nowhere more so than in this work, where the 'I' of the McCahon image operates as an absence, a gap between two disparate sources.

Victor Meertens, Korero 1987 galvanized iron, galvanized iron primer & wood, 354 x 130 x 114 mm.

There were several artists I was surprised not to see included — Juan Davila, Richard Dunn, Jenny Watson and Vivienne Shark Lewitt are just some that come to mind. It would have been interesting to have viewed the extraordinary Neo-Symbolist images of women bathers by Annette Bezor (which are in the exhibition) alongside Julie Brown-Rrap's reworkings of nineteenth century paintings of the female nude (which are not). Both are feminists, deconstructing similar conventions but in different ways. Given these absences, there are some inclusions which seem to me to be of dubious merit—Victor Rubin, Dale Frank and Marianne Ballieu, for instance.

Australian painting, as exemplified by this selection, is noticeably bigger, more apparently confident, at once brasher and less tasteful, and more stringent than the work in NZXI (and perhaps than painting generally in New Zealand).

Another major and important difference between the two shows is the representation in the Australian exhibition of work that draws directly on indigenous traditions of artmaking, in the paintings of Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri and Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri. Tim Johnson's Yuendumu also shows traces of Aboriginal influence, though not as much as some of his former paintings. (Johnson's works, like Meertens's Maori titles, raises the issue of the ethics of appropriating from less privileged cultures — an issue that has skirted in the catalogue, and more generally in relation to Johnson's practice.)

Like NZXI this exhibition shows us the institutional face of the arts, a face that has come in for criticism recently. In Australia there have been critiques of the blockbuster nature of the latest Sydney Biennale, for instance, and here during the exchange of letters to the Listener (and elsewhere) following NZXI, there were a number of references to 'the art mafia', art world 'buddies' and 'the Auckland art elite'. I must confess to feeling some irritation over these last comments (particularly as they all came from writers in main centres—things are undoubtedly tougher for artists in the provinces). Art practice doesn't, after all, begin and end with the big institutions and there are a number of other options for artists working in this country—often, more than elsewhere. Barbara Kruger and Alexis Hunter, both internationally successful artists who visited here earlier this year, expressed considerable surprise at the ease with which even very young and inexperienced artists in this country are able to show their work in dealer galleries.

Apart from the Auckland City Art Gallery Auckland has, at present, perhaps twenty galleries holding exhibitions on a reasonably regular basis as well as several other occasional and/or non-gallery venues. Virtually every medium, style and mode of artmaking is represented and there is undoubtedly room for the young or beginning artist. Star Art, for instance, has a policy of showing such artists: not surprisingly, this can often make for uneven exhibitions, but even these may display glimmers of promise.

One more resolved, though somewhat cluttered, exhibition at this gallery was Neil Miller's recent show of sculpture: greater experience on the part of artist and dealers alike would perhaps have led to some pruning to give emphasis to the best works. Made mostly from mild steel rods with larger metal areas pieced together in an agreeable patchwork texture, Miller's sculptures suggested a pared down and whimsical David Smith at his most fluid and graceful. Though they were primarily abstract, some of the more successful—for instance, Trick Cyclist or Speaker (a large megaphone-on-stilts)—made oblique reference to the human figure.

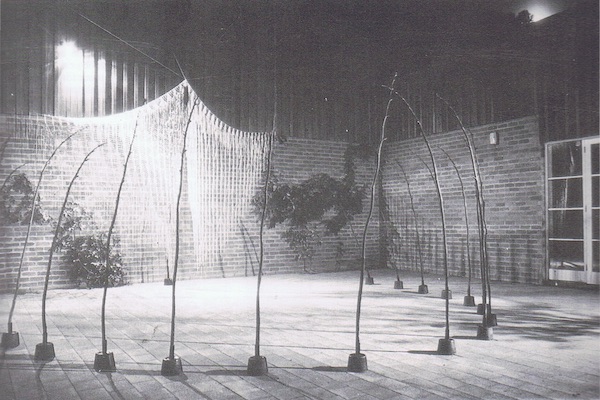

So too did Maureen Lander's outdoor installation at the Fisher Gallery in May. It was part of New Directions in Fibre, an exhibition that, over-all, I found a little disappointing, not as adventurous as its title promised. (Aside from Lander's work, Jenny Hunt's First Writhe, some thirty small hieroglyph-like forms wrapped, painted, bound and arranged in rows on the wall like the ciphers of a text, was perhaps the most unexpected and interesting work on view.)

Maureen Lander, Talking to a Brick Wall , installation at the Fisher Gallery 1988 - at night with moon rise

Sited appositely against the brick wall of the Fisher's sculpture court, Lander's Talking to a Brick Wall consisted of a huge drape of clear nylon netting hung with flax piupiu quills. Before it was arranged a small congregation of seeding flax stems, each anchored in a concrete base. The delicate hanging bore connotations of a protective cloak and, with its divided and inverted triangular form, the female vulvae. (Perhaps not coincidentally, the paired triangle representing both cloak and female principle formed the basis for several of Kura Rewiri-Thorsen's geometric abstract paintings at Gallery Pacific in the same month. Rippling and swaying in the lightest breeze, flexible yet strong, the drape acted as mediator between the unyielding wall and the anchored flax stems, suggesting, as Lander’s work invariably does, the possibility of discourse and interchange. Characteristic, too, is the simplicity and assurance with which she (like the Aboriginal painters represented in Advance Australian Painting) manages to weave together elements of an indigenous culture and a colonising one, without denying or detracting from either.