Te Maori in New York

HIRINI MOKO MEAD

Before even the fourth week ended 70,000 people had been to see Te Maori. By the end of its time at the Metropolitan Museum of Art on January 6, 1985 some 300,000 people should have seen it in New York.

Long shot showing the Pukeroa gateway (front), the Te Kaha pataka carvings to the left and maihi from a Ngati Porou house built at Rotoiti.

It opened in a spectacular way at dawn on 10 September. Some of the Americans thought with dismay that we were planning some sort of Hollywood extravaganza. Others suspected that it was nothing but a publicity gimmick by a media-starved little nation. But when the morning came and the American officials and guests were lined up at the doors of the Metropolitan Museum and the Maori and New Zealand group began moving up the stairs, chanting as they approached and with stripped down warriors keeping order: that was the moment of understanding. The Karanga (ceremonial call) echoing across the streets clinched it. The rituals had begun and it was no gimmick.

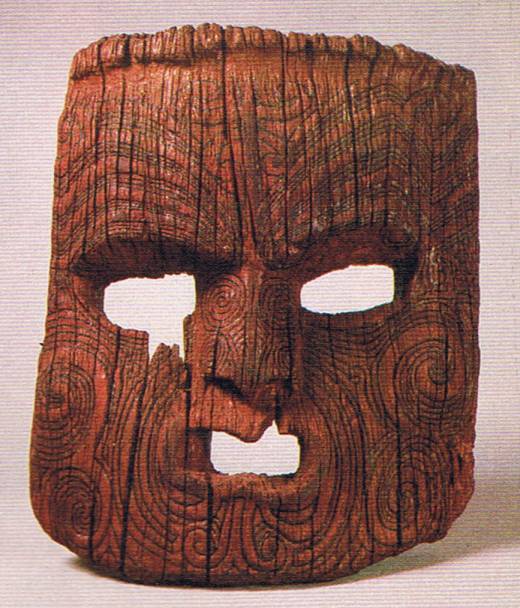

Mask from the Gateway to a Pa wood, 640 mm. high, Whirinaki River, Okarea, Ngati Manawa tribe, Te Huringa I period (1800-present) (Collection of the Otago Museum, Dunedin)

The great doors of The Metropolitan were opened and into the building we poured. Led by the chanting priests Sir James Henare of the North, Ruka Broughton of the Wellington region, Monita Delamere of Mataatua, the Maori group snaked its way towards the exhibition area upstairs. Then followed the hosts—the American party consisting of officials from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The American Federation of Arts, and Mobil Oil. That impressive kaumatua (elder) Henare Tuwhangai performed the rituals in the exhibition area and by the time Piri Sciascia and I arrived with the American party he had finished.

Amulet, Hei-tiki greenstone 90 mm. high, Bay of Islands, Ruapekapeka, Ngapuhi tribe, Te Puawaitangi period (1500-1800) (Collection of the Otago Museum, Dunedin)

Now the rituals of encounter were to begin. The Maori side was positioned near the Pukeroa gateway of Ngati Whakaue, Rotorua, with Peter Sharples, the warrior of Ngati Kahungunu immediately before. Time magazine caught his image for posterity (see illustration). Facing them were the American hosts, their speakers seated and ready to begin the speeches of welcome. By the time the Hon. Mr. Koro Wetere, Minister of Maori Affairs, had declared the exhibition open, and we had finished our karakia (church service), the frenzied clicking of the cameras of the international press present at the ceremony assured us all that this was a historical moment, a break-through of some significance, a grand entrance into the big international world of art. We had suddenly become visible.

Doorway for a Storehouse, Kuwaha pataka, wood and paint, 1150 mm. high Whakatane, Ngati Awa tribe, Te Huringa I period (1800-present) (Collection of the Auckland Institute and Museum)

Douglas Newton, chairman of the Department of Primitive Art at the Met, had no doubt that the exhibition would be a great success. He assured me of this months before the opening. But even he was delighted with the response of the media, of the people of New York and of the art world in the United States. When the Te Maori cultural group performed at the American Museum of Natural History there was no doubt something had happened. The audience was already won over even before the performance began. What they wanted was to touch Maori culture and Maori people to learn more and more and more. They were reaching out to us in a way that is difficult to describe.

Palisades and palisade figures which separate thr exhibition area from the great Egyptian Hall

The New Yorkers we were told were 'tough to please'. If we didn't do things right they would get up and leave. But that did not happen. Instead, 500 people were shut out because the house was full to capacity. These hard New Yorkers were really softies at heart—just like us. Yet not quite. Their response was warmer than anything we had seen in New Zealand.

Inside the exhibition area where Te Maori is displayed. The New Zealand group from left. Mr. Ruka Broughton (behind glass) Mr Sonny Waru, Mr Kara Puketapu, Archbishop Paul Reeves, Archdeacon Kingi Ihaka, Mr Henare Tuwhangai (partly obscured) Mr Bruce Gregory, Hon. Mr Koro Wetere, Minister of Maori Affairs, and Dr Peter Sharples.

It took nine years to put the exhibition together. Many different people have had a part to play in the transformation of the original idea, born in New York, to the reality of Te Maori. On the American side the Metropolitan and the American Federation of Arts did the major negotiating, while on the New Zealand side a Management Committee was established in Wellington to handle the complexities of a major exhibition. Certainly the outstanding fact about Te Maori was that it represented a huge and very complicated event. That it was a learning experience for all of us is now clear.

Post figure, Poutokomanama, wood, 1440 mm. high Napier, Pakowhai, Ngati Kahungunu tribe, Te Huringa I period (1800-present) (Collection of the Hawke's Bay Art Gallery and Museum)

Today as we look back at its great success, the people who struggled with the idea, Kara Puketapu, chairman of the Management Committee, Hamu Mitchell and then Piri Sciascia the executive officer and members (representing Maori Affairs, Internal Affairs Foreign Affairs, Trade and Industry and MASPAC) can feel happy at the results. To be sure we did not handle all of the problems perfectly, but then this was a new experience. Calling the tribes together; talking to them about the idea of the exhibition and then seeking their support and agreement to participate: this was all new. Going to the people and not dealing only with museum officials ruffled some feathers. Learning to work together, with Maori leaders such as Kara Puketapu, Hon. Mr Ben Couch, Piri Sciascia and myself playing a prominent part in the negotiations was also new. This was the first time in history that the Maori people were actively involved in negotiations for an international exhibition of our art. It was the first time, too, that we called the tune and decided what had to be done. After the opening day at New York ended everyone was sure that we had done the right thing.

Lintel, Pare, wood and shell 2350 mm. wide, Paetonga, Ngati Tamtera tribe, Te Huringa I period (100-present) (Collection of the Auckland Institute and Museum)

Some of our people still doubt the wisdom of bringing our art objects to the United States. All I can say is that I personally feel that we made the right decision, that our ancestors who carved these beautiful taonga needed to have their work and their genius recognised internationally, that when the cultured eyes of the world saw they would acknowledge the greatness of our ancestors. That indeed has happened. The Metropolitan is the world when it comes to art. There is no doubt of that. Our ancestors have now lifted all of us up high so that we can feel good about being Maori, about our culture, our language and above all our art. To the international community our art is stunningly beautiful and it is world-class.

The Taranaki priest, Mr Sonny Waru has commenced the ritual chanting that will take the group to the door of the Metropolitan Museum. This group is flanked on either side by impressive and popular warriors—Mr Jerry Rautangata, an architect, on the left, and Dr Peter Sharples, extreme right. New Zealand's ambassador at Washington D.C., Hon. Sir Lancelot Adams-Schneider and his wife, are with the group. Hirini Moko Mead is Professor of Maori at Victoria University, Wellington, and edited the book, Te Maori: Maori Art from New Zealand Collections, published by Heinemann in association with The American Federation of Arts.

The total Maori population in New Zealand and around the world can rejoice in the success of the Te Maori exhibition. With us every citizen in our country can feel the sweet taste of success and rejoice in being a New Zealander. But though we now have much to celebrate, there remains a great deal of work to do. After New York the exhibition goes to St. Louis and San Francisco. Others are clamouring to have it too but I hope it goes home to be exhibited at Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch so our own people can see this great collection of art work.

When we look again at the works of our ancestors we should see and understand.