Meaning, Excellence & Purpose

ANZART In Edinburgh

MICHAEL SPENS

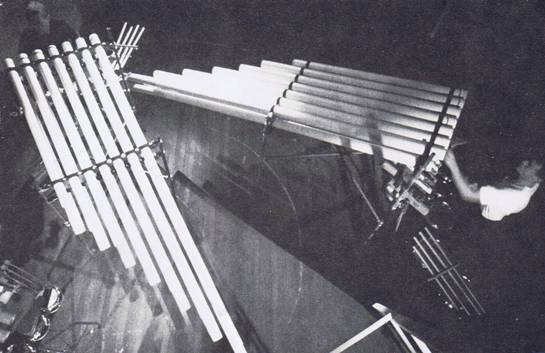

The title for the Australian component of this year's ANZART show in Edinburgh was `Meaning and Excellence'. This could equally well have applied to the New Zealand element of the exhibition. Not that there was the same priority given to meaning in the over-all quality of the New Zealand work—in a context where expressionism is paramount. Wystan Curnow, as curator, achieved by good foresight (he had diligently observed Edinburgh's chaos a year earlier) that which on-the-spot logistics could not alone secure—a convincing demonstration of the quality of current work in New Zealand. It was an enlightened move to include the group From Scratch. As the London Guardian correspondent wrote: `Their music seemed close to improvisation, though it was in fact, formally, controlled and led one's attention to new sonorities and rhythmic patterns at invariably the right moments.'

New Zealanders at the Edinburgh Festival Left to right: unknown person, Alison McLean, Don McGlashan, Wayne Laird and Richard Killeen

The project for a combined ANZART exhibition appears to have originated with Richard Demarco. It materialised jointly, however, through the persistence of its advocates on both sides of the Tasman. To Australia it seems to have been one of a whole series of orchestrated export exhibitions, in venues from Los Angeles to Brooklyn and Manhattan. For New Zealand, however, Edinburgh was the more important for its singularity. While there is now a sequence of exhibitions exported from New Zealand, apart from the great Te Maori show at the Metropolitan Museum in New York they have been smallish one-person shows (such as those of Billy Apple, Philippa Blair, Richard Killeen and Philip Trusttum in that city). Any critic invited to select for such a show as ANZART therefore faces difficulties.

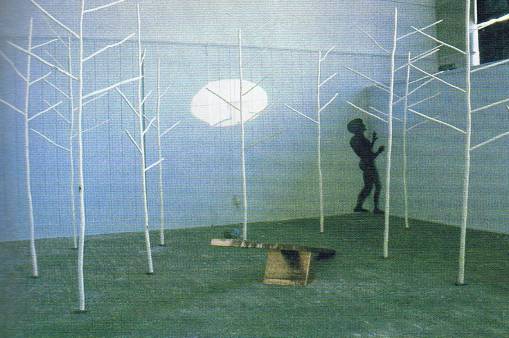

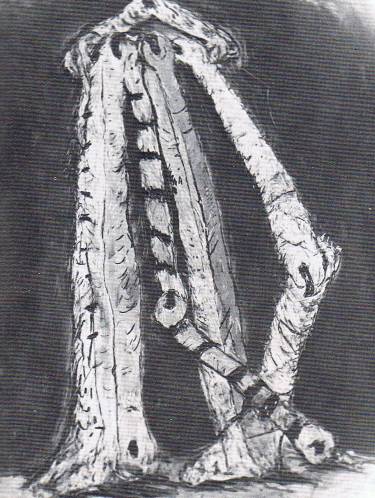

ANDREW DRUMMOND Sentinel (detail) 1984

The New Zealand strategy, if one can so describe it, was to include one major blockbuster — Colin McCahon, straight from the Biennale at Sydney—showing him in a separate exhibition space in the Talbot-Rice Gallery at Edinburgh University. The choice of McCahon in this connection was highly appropriate. At the Edinburgh College of Art, where the remainder of the work was hung, or installed, the disposition of forces was, so to speak, broad in scope and flexible in content. In contrast to the Australian rooms with their measured coolness, the New Zealand work exhibited a playful individualism, aloft between anarchy and self-fulfilment, redolent with expressionism. The spaces available for installation were high-ceilinged and North-lit. Curnow made full use of this.

Andrew Drummond's in situ installation, Sentinel, made skilful use of tree elements: something more readily understood in the light of the artist's perhaps over-lengthy stay (as artist-in-residence) on the treeless North Scottish Isles of Orkney. The second piece he had exhibited, The starter and stoppages from the journey of the sensitive cripple, with its suspended walking-stick, was unpredictably appropriate in Edinburgh too, for a city having a disproportionate high quota within the United Kingdom of physically handicapped or cripple people, or war-torn aging victims of conflict.

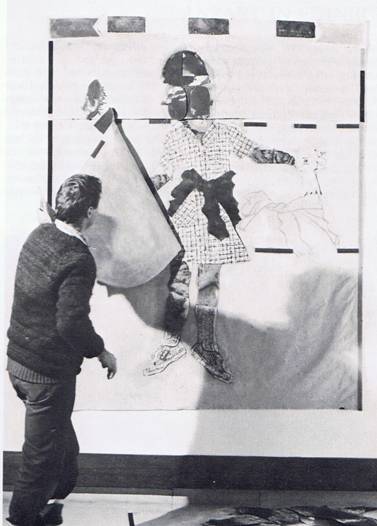

Philip Trusttum with hisBook of Dreams 1984

Philip Trusttum's work made a considerable impression upon the festival-going public. Once again, a major in situ installation confronted the visitor: a tableau recognisably of Richard Demarco and the New Zealand artists in suspended animation, outdoing Keith Haring's graffiti figures in their highly individual gestures. Trusttum's humour breaks through again in Lee's Table yet he astutely, intuitively resisted pursuing a project on Tartan which prior to departure he described to me at home—indeed there surely is too much of it around—carefully he avoided the pitfalls of remigrate romanticism, in a city literally afloat in the material.

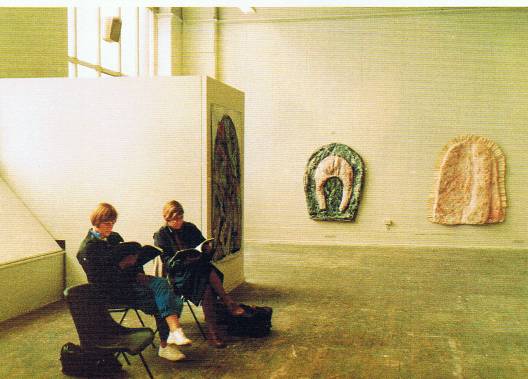

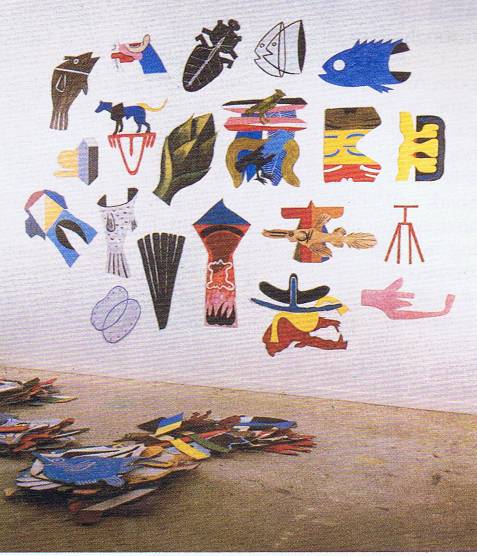

Installation photograph showing three works by Maria Olsen

Maria Olsen's tendency is inclined also to playfulness. She hovers on the edge of laughter. 'The situation I like is the moment of mirth, before the laugh', she said. Indeed there is a momentariness, and a momentousness about Olsen's work. The reliefs are undeniably powerful, and it must be said redolent not of the North Atlantic of Olsen's roots, but of the South Pacific area she inhabits. The atavistic and rounded forms of such sculptured reliefs as Frill and Threshold draw upon those deep responses which humans try to deny, but cannot but recognise. The two productions by Gregor Nicholas, Body Speak (1983) and Every Dancer's Dream (1984), together with that of Peter Wells, who showed Little Queen, were strongly representative of the video and film experimentation to be found in New Zealand.

RICHARD KILLEEN Pooled Memory and Some Empty Fish 1984 Winsor and Newton alkyd on aluminium (20 pieces)

Richard Killeen is a New Zealander whose reputation is now well established outside New Zealand. Killeen has evolved his own response to the liberation from the picture frame in the form of a visual language based upon cut-out and coloured metal shapes. The images, more often than not, are easy enough to identify. Killeen chose to show, in Edinburgh, the assemblage Appropriation No 2. The visual `phrases' which resulted from this conjunction of shapes were an articulate expression of this language. It would also have been valuable if the collection of images which he draws methodically in notebooks, as a separate but related activity, could have been on show. But all this was a fitting evocation of the statement by Roland Barthes, `Meaning is above all a cutting out of shapes'. There is no transcendency in such works—only the now. And even that Killeen authenticates by its removal.

It is difficult to exclude the consideration of other artists of whom these selected are, after all, representatives. As at the Sydney Biennale, I would have liked to have seen Ralph Hotere's works included, since Scotland is a land which shares Hotere's preoccupation with environmental issues. Yet few Scottish sculptors have chosen to confront such issues. Among other alternatives I could also have included the canvases of Philippa Blair, who showed extremely well in New York last September. Jeffrey Harris looked impressive. And I believe one of the major oversights of the exhibition was the absence of any of the New Zealand photographers which have been so assiduously nurtured by Luit Bieringa, Director of the National Art Gallery, Wellington. The work of Peter Peryer, Laurence Aberhart, Gillian Chaplin and Anne Noble, for example, exhibits a laconic proficiency that is very much of contemporary New Zealand.

MARIA OLSEN Untitled Drawing 1984 pastel on paper

In this article I have concentrated very much on the work of the New Zealand artists. Looking at the ANZART show over-all, however, one cannot avoid being impressed by the coolness and rationale behind the Australian work. There is a reverence for structure, or its deliberate disengagement as such, which runs like a common thread through all these Australian works.

Geoff Lowe's Impersonation is a powerful figurative painting which retains an enigmatic, mannerist quality, part of which derives from the clutched boomerang, part from the masked, possibly aboriginal face. Likewise Vivienne Shark LeWitt's frozen figures denote an anxiety that is barely rationalised, leading to questions which remain unanswered. Peter Tyndall's A person looks at a Work of Art ... someone looks at something seeks to demystify the process and the subject simultaneously. It was a bonus to see the diaristic paintings of Robert Rooney, revealing a shared imagery which is broad in its appeal socially, yet acknowledges a signing system which has itself become debased by historical categorisation and mythology. John Lethbridge's Concise History of the Universe acknowledges the visual language of the Constructivists while relying upon the artist's own inherent codification of figure, gender and form to convey or rather to filter new meaning. Howard Arkley, however, trusts to the immediacy of visual elements already encoded. Linda Macrinon's beguiling paintings parody the variable of gender.

From Scratch performing

It was for the performance artist Lyndal Jones, fresh from Los Angeles, to create a paradigm for all that was superlative from Australia. Her Prediction Piece No 7. Versions 1,2,3 explores the disavowal of power within the matrices of chance. Power operates like a spider across the parameters of probability. There are known futures' and there are `unforeseeable futures'. Certain recognisable elements are found within this plane: a letter, an overhead plane, a wall, a box of Chinese photographs, an actor in evening-dress, spotlit in a darkened theatre. Such an actor, female, carries flowers. Inevitability is designated a myth, set within an organised mythology. Lyndal Jones demonstrates the interplay of 'stories', of a Romance, of Executions, of a child of nature. She elaborates the vulnerability of the presumed structure, the waywardness of the 'spider' traversing the web of power, claiming access, trapped in fantasy of future. Jones is a post-modernist phenomenon, yet her roots might be found in the ironic scepticism of the European nineteen-twenties: she balances laconically between virtuosity. rationalism and anarchy. Her stages could be Constructivist. She has no need of props.

Lyndal Jones is moving Performance beyond the Expressionism of Sylvia C. Ziranek, into a new anticipatory stance. In that she can singularly represent the new Australia she must again be more widely seen, 'exported', the symbol of all that is significant of Australia's new. deeper cultural rooting.

Two stills from Peter Wells's work

As Wystan Curnow said in his catalogue essay, New Zealand was discovered some time in the reign of Macbeth, by Polynesians. The performance shown by John Cousins of selected works constituted a worthy succession in as authentic a contemporary vein as those precursors would themselves have claimed.

A special word of praise has to be given to the Australian curator Denise Robinson, who, facing blank chaos on arrival in Edinburgh at the beginning of the exhibition, with no public-relations facilities provided, pulled the whole thing off. The Venice Biennale is as well organised as a May Day Parade in comparison with the context for assembly from which she had to build.

This reviewer had in the course of a peripatetic year found himself more than once flying through Pacific cloud-banks, musing obsessively, but with an increasing rationale and awareness of the power, authenticity and persistence of the burgeoning cultural spheres of Australia and New Zealand. Their strength and regenerative force is a new element in world culture, accentuated by the very distinctiveness of each culture. Much of it must be exported, lease-lend, to flagging `centres'. Can it be that Australians and New Zealanders will occupy New York spaces in the same way that Americans so opened up Paris in the Hemingway days?

Michael Spens is the editor of Studio International, published in London. He made a visit to New Zealand earlier this year.