Exhibitions Auckland

CHERYLL SOTHERAN

Merylyn Tweedie Neil Dawson Marté Szirmay

The refurbished galleries at New Vision have provided useful spaces for some striking nonfigurative shows: James Ross, Gretchen Albrecht - as well as works by artists who maintain a more apparent connection with the observable world: Victoria Edwards's large paper sculptures, and, in late August, Marté Szirmay's New Works, a collection using the shell image expressed in light and fragile forms on table pedestals, or in wall pieces.

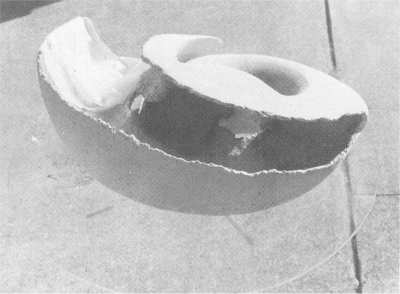

Szirmay has used fibreglass, in molten form, to add to the representational dimension of these images: they appear washed with sea water, or seem to contain pools within their fragile; curled shapes. The glutinous appearance and lurid yellow colour of some of the works makes them appear a little less like confections; perhaps giving a touch of necessary nastiness to the over-all impression of delicate beauty. Another antidote to perfection lies in the broken shapes of some of the sculptures: while the show exhibits the usual technical professionalism of this artist, the reference to the eroding and decaying power of natural forces provides some visual tension.

MARTÉ SZIRMAY Circle #12 1984 cast paper, fibreglass/resin and polychrome, 500 x 500 mm.

Szirmay's show benefited from the expansive space it occupied; but the small gallery at New Vision continues to impose a rather cramped viewing experience. It is, inevitably, a kind of relegation area; it's hard to step back from the works, and you're forced into a close scrutiny, work by work. This isn't always a disadvantage, of course - with the works in Merylyn Tweedie's Photographs & Additions it was entirely appropriate. This artist has previously shown in group shows, working in photography, collage & artists' books, and stood out as having distinctive and unorthodox approaches to rather orthodox subject matter. Her theme is personal: aspects of women's urban (or suburban) existence: stereotyping, categorisation, the accumulation of material goods, the paraphenalia of domestic life and child care. This isn't new subject matter, because for many women it isn't a new experience: the matter of their every day life continues to be valid material for art making. What gives an artist like Merylyn Tweedie's work an impact and an edge, what makes it function not so much as documentation but as a critique of that suburban life, those stereotypical attitudes, is her distinctive choice of image, and her very individual style. It is clear from stylistic choices she makes that this is political art: the use of repeated photographic images, with their combination of documentation and comic strip bluntness; her use of words, written around the images, spelling out messages, shows that she is not after a neutral audience, and that she rejects detachment herself. However these are not glossy images, they do not seduce, although the apparent subjects are conventionally seductive: household objects, under - clothed women. These images have an awkwardness, even crudity about them; the forms are blurred, and accidental colour effects, usually pink, bleed into and out of the frames. The trade-marked film edge remains part of the work, recording the process, and the artist has hand-written comments, quotations, explanations as part of the works. This hand-written script is itself child-like and somewhat crude; there is tension between its naivety and the adult fantasies, the devastating judgements that the words offer. The images and narratives vary from the utmost banality of suburban existence (as in the amusing Man the Cake Stall Girls, in which a cake remarkably like a cow pat presides over a lace tablecloth and gives an opportunity for a sardonic comment on sexist language conventions) to Classical and Renaissance imagery featuring Great Sexist Images/Pronouncements of the past: Judith and Holofernes, Aphrodite, and various Renaissance sages are subtly counteracted by under stated versions of the day-to-day experiences, insights of the artist's friends.

These images are not static; they record experience. The experience may be ordinary, but the artist refuses to let her vision become contaminated by triviality. The avoidance of slickness, the edge of bitterness which can become almost savagery, or can reveal great tenderness is what makes these works memorable The most effective pieces seemed those in which economy of image was matched by curt linguistic elements. Occasionally (as in a work dealing with the demeaning nonsense of the Mills & Boon culture) there seemed too many words, Of course this could be seen as a way of conveying the flowery overstatement, the offensive euphemisms of 'Romantic' prose, and this artist generally seems too much in control of image and text to exhibit radical failure of judgement. Nevertheless, the strongest images for me were those in the work-book which accompanied the exhibition, in which line drawings in savage red accompanied embryonic versions of later works.

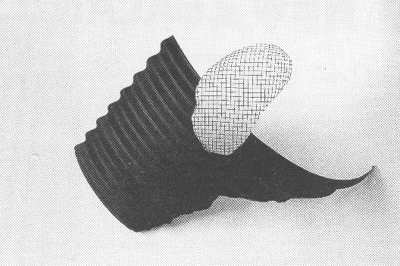

NEIL DAWSON Sunset Construction (Corrugations) 1984 corrugated iron and mesh, 870 x 870 x 260 mm. (irregular) (Collection of the Auckland City Art Gallery)

At Denis Cohn Gallery in August Neil Dawson showed a collection called Sunset Constructions, in which, as he said: 'the works attempt to capture, in a three-dimensional form, personal observations and experiences derived from sunsets. They use colour, visual contrast, scale-material associations and inferred movement.. .' - all familiar characteristics of this artist's ability to create tension between the perceived and the imagined. The variations in scale which had been apparent in earlier shows were supplemented here by attention to lighting effects: appropriate to the atmospheric conditions which the show derives from, but far removed from mere clever representation. Dawson, as well as giving us reference points in nature, also expertly manipulates our expectations about the spaces which art objects occupy, and the, effects of which they are capable. His works thus produce a very traditional sense of wonder at technical achievement with a totally contemporary impression of being plunged into perceptual flux.