The Sculpture of Molly Macalister

ROBIN WOODWARD

The first major retrospective of the work of Auckland sculptor Molly Macalister was on show at the Auckland City Art Gallery from 9 November to 12 December 1982. It was a comprehensive exhibition of Macalister's sculpture supported by sketches and photographic material. To accompany the exhibition the curator, Alexa Johnston, has produced a thorough and well presented catalogue that includes an 'article on the sculptor's work, reminiscences of Macalister by ten of her friends, a brief biography of the artist, detailed information about the works on display and complete photographic coverage of the exhibition.

It was not until 1964, almost thirty years after Molly Macalister had begun work as a sculptor, that she received her first major commission, the Maori Warrior for downtown Auckland. Prior to this only three of her works had found their way into public collections.(1) In addition Maori Youth with Child had been bought for Victoria University, Wellington in 1959 and two years later The Last of the Just was purchased jointly by the Students' Association and staff members for the Hamilton branch of the University of Auckland.(2) In style, subject and medium both pieces are typical of Macalister's work of the late 1950s. In these years she concentrated on representations in concrete of the human figure, frequently elongated, often unnaturally thin and usually arranged in clear and simple lines. Such features reflect an awareness of the work of the Italians Giacometti and Marino Marini, whose influence she readily acknowledged.

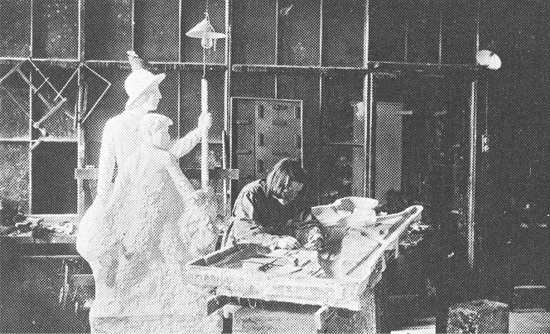

Molly Macalister

- assistant to

Francis Shamrock

on panels for

Education Court,

Wellington 1940

Within New Zealand the artist who had the greatest influence on Macalister was Ann Severs, an English sculptor, who began to work here early in 1958. Inspired by Severs's example Macalister increasingly turned from the wood carving of her early days to modelling in both clay and plaster. Her preference for modelling led to a desire to have work cast in bronze. She was frustrated in this by the virtual non-existence of artistic bronze casting facilities in New Zealand at that time. Fellow sculptor Alan Ingham had cast some of her first models, such as Pair of Birds: but in 1955 he had left for Australia. At that point Macalister had begun experimenting with concrete. At least initially, working in concrete was only a substitute for producing a finished work in bronze. Yet over the next five years she mastered its use, learning to cast in it as well as to model directly in concrete over a steel armature.

Despite this, her desire to work in bronze continued. It was at last appeased in 1964 when she was invited by the Auckland City Council to sculpt a bronze figure of a Maori warrior to stand outside the Chief Post Office in Queen Street. In an unusual move the City Council approached the sculptor on the strength of her exhibited work. More commonly, sculpture financed out of public funds was selected by competition. Equally unusually, Macalister was given only ten days to produce a design of 'a Maori figure in traditional form'(3) - this was the guideline laid down by the City Council. In response she produced a sketch of a warrior clad in a knee length cloak, feet astride in a challenging pose, holding a taiaha (wooden spear) across his chest. On presenting this initial design to the Council the sculptor was careful to stipulate on the sketches that 'these drawings represent only the germ of an idea not the finished article'.(4)

MOLLY MaCALISTER

Little Bull 1967

bronze, 1150 mm.

(Collection of The

Hamilton City Council)

Such a rider was to prove important because she was to modify the design significantly before the statue was completed. In the final full-scale plaster model the warrior was in a much less active pose, the figure was wrapped in an all-enveloping, full-length korawi cloak and was holding a mere, a symbol of peace, instead of the more warlike accompaniment, the taiaha. In producing this monumental image of dignity Macalister specified 'I wanted to get away from thinking of the Maori just in terms of hakas and poi dances'.(5) In fact she achieved this so successfully that some councillors queried whether she had followed their directive, and they called for a warrior in a more traditional fighting pose. Such was their consternation that the Council ordered a stay of proceedings while legal opinion was sought. The order suspending casting caused a delay of two months and was lifted only after the City Solicitor had advised that the sculptor had indeed satisfied the terms of her contract. This was not the first hitch in the commission. Controversy had flared up on two earlier occasions: once when Auckland Maoris protested that the City Council had committed a breach of etiquette in not consulting them about the sculpture and again when the City Engineer had recommended alternatives to the agreed siting of the work outside the Chief Post Office. Even when the statue had been cast and the site finalized Macalister's problems were not over. Her submission that the figure be placed with its back to the Post Office and stand virtually on ground level was not accepted by the Council. Instead the figure was placed looking out to sea from atop a six foot pedestal. Macalister appealed against this arrangement on the grounds that it did not sufficiently take into account the scale relationship of the work to its environment. The statue had been proportioned to stand at ground level and designed to be seen against the backdrop of the Post Office building. The sculptor's objection was overriden. To aggravate matters she then had to take the backlash from the public, many of whom criticised the proportions of the statue, complaining in particular that the head was too small for the body (it was likened to 'a pimple on a pumpkin').

Much less controversy surrounded the selection in 1967 of Little Bull for Hamilton. This work was chosen from five competition models to be the Jaycees' centennial gift to the city. Despite initial criticism of the piece it proved sufficiently popular to be paid for in part by public subscription. Most especially it has always attracted children. Seconds after the unveiling ceremony youngsters were clambering all over the benign Little Bull and even during the official speeches a succession of children had left their parents to fondle the animal. Their enthusiasm suggests that Macalister fulfilled her intention. Her aim had been to create a work that would both appeal to adults and entice children to play on it. The sculptor also intended her work as a reminder of Hamilton's growth in relation to the dairy industry. To this end she explored a variety of ideas working initially on representations of farming figures before finally settling on Little Bull.

MOLLY MaCALISTER

Seated Figure 1966-1968

concrete, 188 mm

Both Little Bull and the Maori Warrior are large scale bronze works designed for outdoor settings. Both are based on large, simplified forms and broad planes with a textured but not detailed surface finish. Neither allows penetration by space and although generalised in form each remains essentially representational. As in most sculptors' work the representational element is strongest in Macalister's portrait studies. Of these, John A. Lee is a typical example. Both the subject and the bust form of this work were decided in 1966 by the commissioning body, the Queen Elizabeth II Arts Council: but Macalister's interpretation of her subject is individual. In this the most distinctive feature is the surface: the lumps of clay were only summarily smoothed into one another, which, even in the final bronze, leaves the marks of the creator clearly evident on the surface of the work. Such a feature is not the only one in which Macalister shows an awareness of developments in early twentieth century European sculpture. This was apparent in both her commissioned and private work long before she travelled to America and Europe in 1962. Some of her earliest modelled portraits, such as the 1946 head of Digby Nelson, show a similarity to Epstein's portraiture; her 1954 Pair of Birds is reminiscent of Brancusi as is her undated maquette for a nine foot high carved kauri pole. Girl with a Pony Tail recalls Giacomo Manzù and the similarities between the Maori Warrior and Rodin's Balzac cannot be denied. Above all though, it is her debt to the strong, angular compositions of Marino Marini and to the forms of Henry Moore's sculpture that most constantly surfaces in her work.

As well as responding to earlier sculpture, Molly Macalister was receptive to the ideas of her contemporaries. This is reflected in the 1968 commission for a relief scuIpture for the new Auckland Synagogue. On this project she collaborated with the architect John Goldwater to design the Ark to house the scrolls in the Synagogue. Basically the Ark is an angled tower eighteen feet high by twelve feet wide. The Ten Commandments are carved into a central slab of Hinuera stone which is flanked on either side by a decorative panel containing carvings representing the twelve tribes of Israel. Here Macalister used traditional animals and symbols associated with the tribes such as the lion of Judah, the wolf of Benjamin, the serpent, the ass, olive trees and towers. Each motif remains recognizable although it is abstracted from its model, rendered in very basic outline and simplified into geometric shapes.

MOLLY MaCALISTER

Maori Warrior 1964-1966

bronze, 3225 mm.

(Queen Elizabeth Square,

Auckland)

Macalister's later commissions are much less closely allied to the figurative, representational tradition. Largely as a result of renewed first hand contact with international sculpture in 1967 her work took a new turn both in materials and concept. The first manifestation of this in her public sculpture is Constellation, designed in 1970 for the B.P. Building in Wellington. Hers was the winning entry in a national competition to choose a work of art for the foyer of the new building. It is an arrangement of polished bronze forms on stainless steel wires attached to the ceiling and to a stainless steel base. Special lighting in the ceiling was installed as part of the design to create an interplay of shadows on the polished base plate. The incorporation of light to such a degree is a new development in Macalister's sculpture and follows international trends. The satisfaction, both personal and public, with this piece is reflected in a work that she created three years later for the chapel at Schnapper Rock Road Crematorium on Auckland's North Shore. Here she repeated the highly successful format of Constellation - the principal difference being that the North Shore sculpture was designed to be set against the backdrop of a flat wall and to be seen from only one angle rather than the multi viewing points of the Wellington work. The move away from traditional sculpture is continued in her 1971 commission for the State Insurance Company. Macalister was given a completely free hand when invited to design a piece to be placed outside the Company's new Auckland building. Here she produced one of the most abstract sculptures of her career, refusing even to give viewers a starting pointing in a title. This piece, one of Macalister's last major commissions, was cast in bronze (despite her work in other materials, bronze was the medium she favoured). With the notable exception of the piece in perspex commissioned by Clearlite Plastics, Auckland, she did not join in the innovations of her contemporaries in the early 1970s who began to use such diverse, materials as latex, fabric, plastics, neon lights and other manufactured products. Of this trend she said: 'the modern techniques and materials are very exciting but another lifetime is needed to start using them'.(6) Molly Macalister's commissioned work documents developments in New Zealand sculpture in the 1960s and 1970s. it includes the use of traditional materials, the standard techniques of carving and modelling, and covers the establishment of large scale bronze casting in the country. Her sculpture demonstrates the beginnings of the move away from these towards a greater variety of materials and new techniques of working them. The scope of her work is also remarkable. It ranges from representational portraiture to untitled abstract forms; it spans relief sculpture, free standing works, indoor and outdoor pieces and architectural commissions. Equally important, it indicates changes in patronage of the arts in New Zealand. Her career reflects traditional sources of work such as private and church commissions, as well bearing testimony to the increased interest of civic authorities in sculptural projects and the rise of commercial and business-house sponsorship of the arts.

1. These works are Portrait of Willi Fels C.M.G. 1941-1942, Otago Museum, Dunedin; Figure 1954, Auckland City Art Gallery and Standing Figure, Auckland City Art Gallery.

2. Now the University of Waikato.

3. New Zealand Herald 8 Dec. 1965.

4. Ibid.

5. Auckland Star 6 Oct. 1965.

6. Auckland City Council file 339/47.