Chance In Art The Indeterminacy Aesthetic

ANDREW BOGLE

As in scientific, so in cultural thought, indeterminacy fills the space between the will to unmaking (dispersal, deconstruction, discontinuity, etc.) and its opposite, the integrative will. IHAB HASSAN

The historian Mommsen estimated that chance accounts for a third of all historical effects. Strindberg wrote a manifesto on its role in art. For the Surrealists it was a means of transcending the barriers of causality and conscious volition. Richter adopted it as a protest against the rigidity of straightline thinking. Duchamp categorised some of his works as 'canned chance'. Arp revered the law of chance as the highest and deepest of laws; as did the great physicist Heisenberg, who, in 1927, sanctified chance in a mathematical formulation.

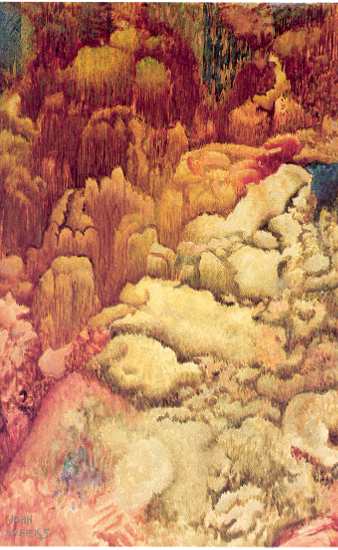

JOHN WEEKS

Fantasy 2 c.1949

oil on cardboard, 600 x 395 mm.

(collection of The

Auckland City Art Gallery)

Heisenberg's famous indeterminacy relation pulled the ground from under the twin edifices of causality and determinism. At the heart of matter, where scientists had sought the key to the universe, Heisenberg revealed that chaos presides and knowledge must finally remain indeterminate. Even Einstein could not accept the shattering conclusion. 'God does not play dice with the universe', he protested.

Chinese Taoist philosophers, some 2,500 years before Heisenberg, saw the universe in terms that quantum theory now compels us to accept. Foregoing the classical Newtonian concept of building blocks of massy particles, which quantum theory dispensed with, Taoism postulated a rhythmical non-material essence to matter which they called ch'i. The material bodies of the physical world they saw simply as temporal forms, like standing waves or changing cloud patterns, created by the universal spirit ch'i. Change, they held, is the only constant in the universe.

Indeterminate patterns on Chinese T'ang and Sung pottery - crackle, flambé, temmoku, marbling and agate - are all symbolic of the ever changing patterns of ch'i which, although in itself formless, gives rise to all forms. Like writhing smoke or eddies in a fast flowing river, these patterns never repeat themselves. By introducing a measure of chance into the creative act in the form of indeterminate fissures, drips, flashes, blotches and streaks, the Chinese potter entered into a dialogue with the eternal processes of Tao and impressed its shadow upon his small subjective creations.

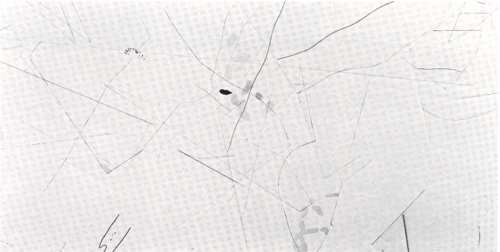

JOHN CAGE

Changes and

Disappearances #7 1979

285 x 540 mm.

(collection of The

Auckland City Art Gallery)

Any work which involves teleological use of a purely objective phenomenon, such as crackle, may be described as aleatoric - a term derived from the Greek word 'alea', a dice. Crackle can be induced at will: but the pattern the fissures take is indeterminate.

Chance can be used in different forms. In mockery of rationalism and traditional scientific thinking, Duchamp devised chance-based units of measurement by dropping threads one meter long from a height of one meter, fixing them with varnish, then cutting wooden templates from the fortuitous contours.

The New York based-composer / artist / writer / philosopher / musicologist, John Cage, regularly consults hexagrams of the ancient Taoist Book of Changes, the I Ching, to attain a Zen state of 'nomindedness' and open himself to alternatives which consciousness precludes from consideration. Cage says, 'I never imagine anything until I experience it'.

Cage, who is perhaps the most committed exponent of indeterminacy in art since Duchamp, is best known as a composer. But his influence has extended to most of the other arts: partly because he has persistently worked at decategorising creative expression to break down the distinction between art and life. Since the 1960s ' he has produced some ten or more editions of prints using chance procedures. Changes and Disappearances is a set of thirty-six unique prints. 'I asked [the I Ching] the same question 36 times and got 36 different answers.' The contours of the many small plates involved in the Changes and Disappearances project were obtained by dropping pieces of string (after Duchamp).

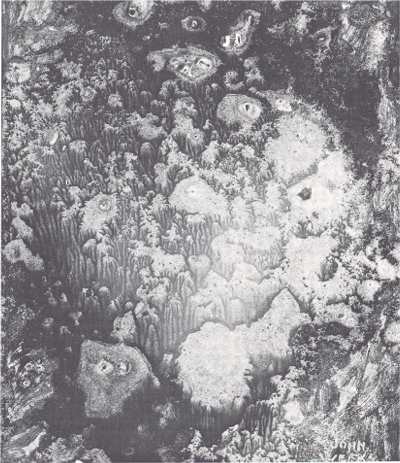

JOHN WEEKS

Coral Study c.1945

decalcomania / gouache,

280 x 240 mm.

Other artists make their compositions indeterminate in an ongoing way. Oyvind Falhistrom's Section of a World Map, a Puzzle(1) invites the viewer to rearrange the printed vinyl elements (picture-organs) which are attached to a metal base-plate by little magnets on their undersides. Rauschenberg has written of Falhistrom's variable works. '. . the logical or illogical relationship between one thing and another is no longer a gratifying subject to the artist as the awareness grows that even in his most devastating or heroic moments he is part of the density of an uncensored continuum that neither begins with nor ends with any decision or actions of his'.

Calder's 'mobiles' (a term coined by Duchamp), which are amongst the earliest examples of kinetic art, possess not one but a continuum of forms that transform indeterminately according to generating currents of air. Richard Killeen's cut-outs(2) which can be rearranged by the viewer to make new compositions are an indigenous example of open-ended indeterminately composed art.

Having outlined the phenomenon of aleatoric art, let us now examine the state of its existence in New Zealand. Apparently it had no significant currency in traditional Maori art. John Weeks is probably the first New Zealand artist to have systematically explored indeterminate image-making. In the late 1940s he produced a number of indeterminate impressions by a process dubbed 'decalcomania' by the first European artists to use it - the Surrealists Yves Tanguy, Oscar Dominguez and Max Ernst.

MAX ERNST

Arbre Solitaire et

Arbres Conjugaux 1940

decalcomania / oil,

815 x 1005 mm.

(collection Thyssen- Bornemisza)

Decalcomania is a form of blotting. Gouache is spread on a sheet of paper; another sheet is laid on top of it, pressed here and there, then peeled off. Patterns produced by decalcomania, as with most indeterminate pattern-making processes, are invariably highly suggestive of universal processes and their manifest natural forms and patterns. Dubuffet, who produced 'empreintes' by a blot technique similar to decalcomania, graphically described his indeterminate impressions as evocative of ' . . richly adorned surfaces like depths of the sea, or great sandy deserts, skins, soils, milky ways, flashes, cloudy tumults, explosive forms, oscillations, fantasies, dormitions or murmurs, strange dances, expressions of known places'.

For the Surrealists the significance of this type of image-making lay more in the subjective process than the objective product. These artists saw automatic techniques as a way of excluding mental guidance and opening up what Klee defined as 'that powerhouse of all space and time - call it brain or heart of creation - which activates every function'. Automatic techniques recommended themselves to the Surrealists, since they required no technical ability, which, anyway, they saw as inhibiting direct dialogue with the subconscious. The automatic artist became less a creator than an interlocutor, picking out and projecting that which saw itself in him.

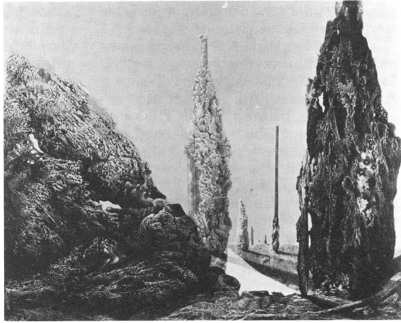

ALEXANDER COZENS

Ink-blot 'landscape'

c.1785

Apart from his decalcomania gouaches, Weeks also made a number of pictures which, at first sight, can easily be mistaken for decalcomania. These fantastic patterns might seem indeterminate: but on close inspection they reveal brushstrokes. Ruled pencil grids underlying examples I have seen suggest they are scaled up copies of his small decalcomania gouaches. The relationship of Weeks' mock decalcomania pictures to his genuine ones is one of intention versus indeterminacy.

There is a remarkable parallel to the above case in a set of pictures by the eighteenth century British artist Alexander Cozens, who developed an experimental method of generating landscape compositions by means of indeterminate ink blots (some one hundred years before the Swiss scientist Hermann Rorschach). Cozens aspired to an ideal landscape art which derived neither from the Old Masters nor from the appearance of nature. In his own words, 'Composing landscapes by invention is not the art of imitating individual nature; it is more; it is forming artificial representations of landscape on the general principles of nature, founded in unity of character, which is true simplicity'. Ironically, from these remarkable blots, which combine a happy mixture of chance and design, Cozens copied stilted mezzotints which hardly hint at the spontaneous splendour of the originals.

PATRICK HANLY

Tamarillo (Second Edition) 1969

screenprint / gouache,

505 x 395 mm.

(collection of The

Auckland City Art Gallery)

There are two types of pottery decoration - agate and feathered slipware - which stand in a similar relationship to each other: the former indeterminate, the latter chirographic. Feathered slipware, which mimics the striated markings of certain kinds of stone, is produced by trailing a feather over fluid slips of two or more colours applied in bands, to imperfectly blend them. On the other hand, agate, which pervades the body of the vessel, is produced by splicing and kneading two or more different coloured clays until suitable stratification is achieved, before throwing the vessel.

The New Zealand potter John Parker has used agate to striking effect. Employing combinations of blue and white, black and white, and pink and grey synthetic pigments to colour his clay, Parker produced a range of both utilitarian and non-utilitarian porcellaneous wares in which he achieved an elegant synthesis of closed form and open pattern. The blue and white agate vessels are particularly evocative of cloud strata which are among the most indeterminate and volatile of natural phenomena.

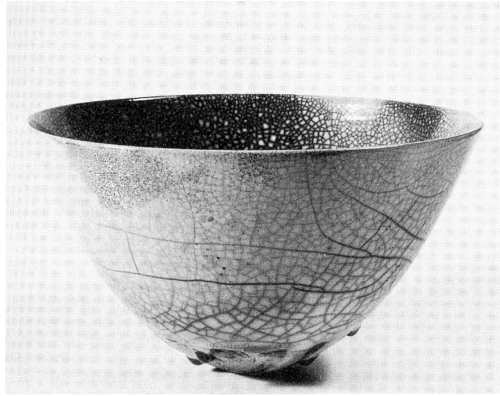

Catherine Anselmi, who studied under John Parker, has made indeterminate patterns a motif of her pottery. To date, she has employed two sorts - crackle and grass smoke - to embellish her low-fired raku wares. Crackle results from the unequal contractions of a vessel's body and its glaze after firing, and takes the form of an irregular network of fine fissures fracturing the glaze. T'ang and Sung connoisseurs esteemed crackle highly on account of its resemblance to the veining and interior flaws of milky jade, a substance they prized above all others. Sometimes, in order to enhance the effect, the Chinese potter rubbed pigment into the fissures and fixed it with an additional coat of translucent glaze.

CATHERINE ANSELMI

raku pot

(crackle) 1980, 110 mm. high

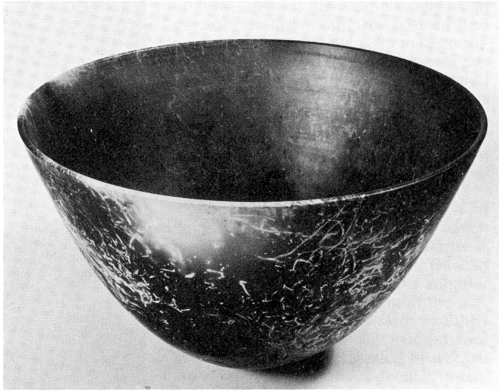

The crackle of Catherine Anselmi's raku pots is enhanced by carbon from sawdust smoke having permeated the fissures which, as a result, stand out graphically against their grey-green translucent glaze. In places, where the pots have been grasped with tongs to remove them from the kiln, the crackle has taken the form of spidery asterisks. Her grass smoked pots are embellished with constellations of smokey sparks dancing over their gunmetal grey bodies. The process by which this effect is achieved is as unlaboured as the results are spectacular. The pot is bisque fired to 1,000°, re-fired in a raku kiln, withdrawn with tongs and finally rolled in a nest of dry grass The heat of the pot ignites the grass which smokes it. Grass ash acts as a stencil to produce the indeterminate white markings which fleck the gunmetal grey colour imparted by the smoke.

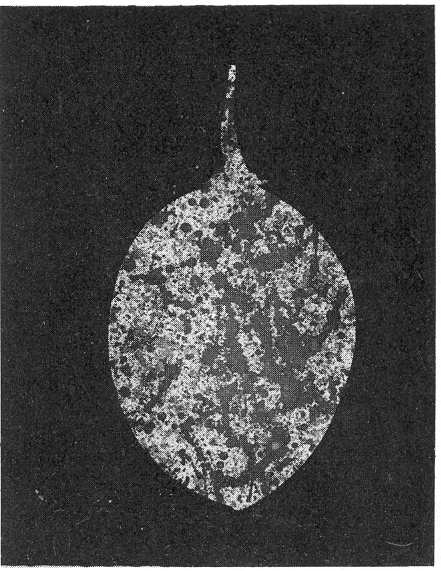

The decoration of these crackle and grass smoked pots speaks eloquently of the processes involved in their making. Combustions and contractions are arrested in dynamic patterns which tell a story of the different forces that have conspired in their shaping. Such patterns are indeterminate and perfectly natural. This relationship of closed form to indeterminate pattern is almost a leitmotiv of nature. Types of fruit, gourds, leaves, flowers, birds' eggs, seashells, for example, possess it. According to an ancient Chinese record, an aesthetic yardstick for the classical Chinese potter was to let neither man nor beast wandering in the forest recognise his wares arranged there.

Patrick Hanly has regularly used indeterminate processes in his art since the late 1960s. His print Tamarillo achieves a similar formal equilibrium to Catherine Anselmi's pots. The egg shape of the tamarillo is awindow on to a milky way of coloured specks of paint, spattered on to the paper by an action-painting technique. The shape of the tamarillo is unmistakable: but the 'pointillist' explosion of colour is decidely non-literal.

The best term to describe Tamarillo and related works from the In the Garden series is 'molecular'. Gardens saturated with a white summer light buzz with magnified molecular frenzy. The thin epidermis of nature which screens from our eyes a world of intricate yet vast complexity is stripped away as if by x-ray vision. The rhythmic loops and drips of colour that envelop the spectator in Jackson Pollock's vast canvases dance on a leaf in Hanly's paintings.

True organic order, as we know it, sets only the general frame and pattern, leaving the precise ways of execution adjustable and, to this extent, indeterminate ... Biologically, it manifests itself in the superiority of laws of development which prescribe only the mode of procedure. but leave the actual execution free to adapt itself to the exigencies of a world whose details are themselves unpredictable.(3)

CATHERINE ANSELMI

raku pot

(grass-smoked) 1981,

140 mm. high

Hanly's 'molecular' prints from that period of the late 'sixties follow aesthetic principle according to which unique objects are intrinsically more interesting than congruous objects produced by serial production techniques. Hanly's contribution to a set of Multiples, published in 1969 by Barry Lett Galleries, ran counter to the purely repetitive serial process by which the multiples of other artists were printed. The linear part of 'Inside' the Garden was printed from a line block: but each print was individually spattered with a variety of colours through hand-cut stencils. The images are not identical, as is common with prints from an edition, but constitute a set of variations on a theme.

The genesis of Hanly's molecular works was a desperate experiment in deconditioning sometime in 1967 when he felt he had painted himself into a corner. And so, in a completely dark studio, he painted blind, not knowing which colours he was dipping his brushes into, or even whether they were on target.

1. Recently exhibited in the Modern Prints Sampler exhibition, Auckland City Art Gallery, with one of John Cage's Changes and Disappearances prints.

2. See 'Richard Killeen Cut-Outs' by Francis Pound, Art New Zealand, Winter 1981, page 34.

3. 'Organic form; Scientific and Aesthetic Aspects' by P. Weiss, in The Visual Arts Today, G. Kepes (ed.), Middletown, 1960, page 193.