Book review

Sage Tea: An Autobiography by Toss Woollaston

Published by Collins, Auckland, 1981

Reviewed by PETER WELLS

'My mother wished I had been a daughter'. Toss Woollaston's autobiography begins with an echo of the opening line of Proust's great work. It is a simple point of departure. For we are embarking on a voyage into the past-the past of one of New Zealand's seminal modern painters. The victory here is that a painter is writing, and he has written honestly, with a constantly probing consciousness that hardly ever allows the book to fall into the pitfalls of 'great men's' autobiographies: bombast, boredom, bridges over areas which might detract.

The interest of Sage Tea seems three-fold: its contribution to New Zealand art history, in its depiction of the state of art in the South; through one person's eyes we experience a break-up of a world and a move into modernism; there is also the interest of Toss Woollaston's own story: of the indecisions and decisions which made him into a force in New Zealand painting rather than one lost name which went down into the abyss of hobbyism. It is the story, essentially, of quest.

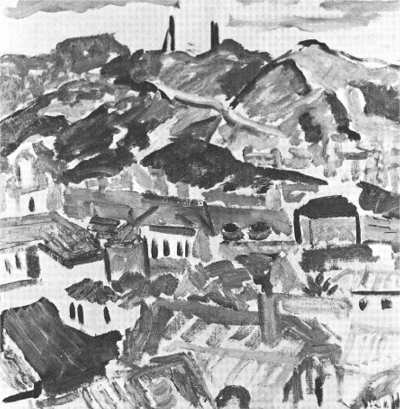

M. T. WOOLLASTON

Wellington 1937

(collection of

Auckland City Art Gallery)

From an early age it is apparent that Woollaston registered colour to an intense degree. His father's forget-me-not blue eyes stare out of the early chapters just as we follow Toss's sight into the inside of a violet. His initial reaction seems to have been that in colour lay karma: in the confines of his provincial background it was the nearest thing to paradise.

These opening chapters offer an historical mirror which in their own way are as accurate in feel as Sargeson. Woollaston writes like an artist - treating incidents as epiphany rather than losing them in the blur of looking backwards. We are occasionally brought face-to-face with moments of truth which have the pattern of art. This is particularly so in the beginning chapters - though, by paradox, these are the most clumsily written: as if Woollaston is finding trouble wording his individual truth.

I emphasise the literary qualities because it is unusual for a painter to command the written word with such finesse that it can contribute a dense background of meaning to his or her art. Part of Woollaston's quest was the struggle against the very un-visual quality inherent to his pakeha birthright. A Sharemilker's son in the shade of Mt Egmont (the very heart of the land wars), there cannot be any more New Zealand birthrights than that.

And for the young Woollaston, not fitting in, it was words that first offered him a stained-glass-window through which to see the 'world beyond'. The bible, the English poets, all gave him a love of language. For his first eighteen years he chose to be a poet.

A world beyond ... Woollaston traces his misery with the world as it was to a sexual root - or more correctly, to the social and religious confines of his time and place. He writes of his sexuality in the manner of one to whom its reality is so great it would never occur to him that other peoples' 'instinctive' reaction would be to hide, to mask, to pass over in silence. A thread of Presbyterian honesty runs through his picaresque tale, an admirable quality of self-scrutiny.

Doubtless this can be traced to his formidable mother. She is a character out of Plumb, with her aversion to the animality of sex married to her desire to get away from the mire of, literally, the cowsheds, but metaphorically the world to which it belonged. First his mother clung to the church - a narrow form of the Church of England - then 'Education'. The thorn in her side was young Toss - his name slang for the very act which made his mother so tight-lipped, at the same time as it was an abbreviation of a more aristocratic forebear's name, to the grandeur of which his mother clung. Two worlds in one, pulling apart.

There were rules in art: line, shading, perspective (just as colour was officially confined to the brackish English school). And these rules effectively blocked any entrance to that 'other world' of the imagination which Woollaston was already moving towards. Even in those days his first essays into paint were of imaginatively created scenes rather than literal transpositions. And there were rules in social and sexual life which, just as effectively, deprived this one human of the right to self-expression.

'Art, for me as a personal practice, died of malnutrition' he writes of those early years in Taranaki. This took an epic for one day when he slaved over a blackboard in front of a school inspector, trying to get two sides of an egg equal. This was the quest of art in Taranaki in the earlier years of this century. And young Toss, finding his technical competence incapable of liberating 'this other world' on to paper, almost gave up.

He didn't give up. The quest became literary and personal. This strikes one again and again in the book: the personal battle of Woollaston, whether he was biking down the length of the South Island on a pushbike and drinking out of puddles in his quest for art: or appearing in the Court of a small town to proclaim his conscientious objection. To seek to enter this 'other world' in the New Zealand of this period was an heroic quest.

A turning point for Woollaston was the sighting of some watercolours in a Nelson drawing room. His return to the world of colour has all the violent immediacy of the long years of exclusion which had preceded it. I knew now I would always paint' he writes of his feelings immediately after purchasing a new range of colours (prussian blue, lemon-yellow, vermilions, rose-pinks). He realised that to enter this i magi native'other world' he had to 'isolate the colours from what they represented, and give them a function and meaning of their own'. He had to grant autonomy to that 'other world'.

His uncertainty, however, led him to attempt to enter this world through the narrow portals of the Suter Art Society of Nelson and the Christchurch School of Art. Finally, dissatisfied, he set off to Dunedin to meet R.N. Field whose painting itself was a liberation: 'it conveyed directly, without the intervention of "subject" the excitement of the act of painting'. We experience, through Woollaston, the very disruptive force that modernism was to New Zealand painting. This takes on a delightful concreteness when he accompanies a boy up to the hills of Christchurch only to find the boy in a state of panic as the sea crept higher and higher up the horizon: in the belief that, if they did not descend the hill at once, the water would come flooding in. It is an echo of the shock which rebounded after the removal of the learned safeness of perspective.

This book is a beginning volume. Yet to read even this book is to experience the small epiphanies in a large life. We have much to be grateful for in the vision Woollaston offers us of a small, chafed and chastened boy sitting on his own in a Taranaki farm cottage leafing through Arthur Mee's Children's Encyclopedia. He comes across two black-and-white illustrations. They are of Sisley's Road to Mont Valerien and Cézanne's Self Portrait. The small boy pauses . . .