Reciprocity

The Early Portrait Photographs of Kevin Capon

JOHN B. TURNER

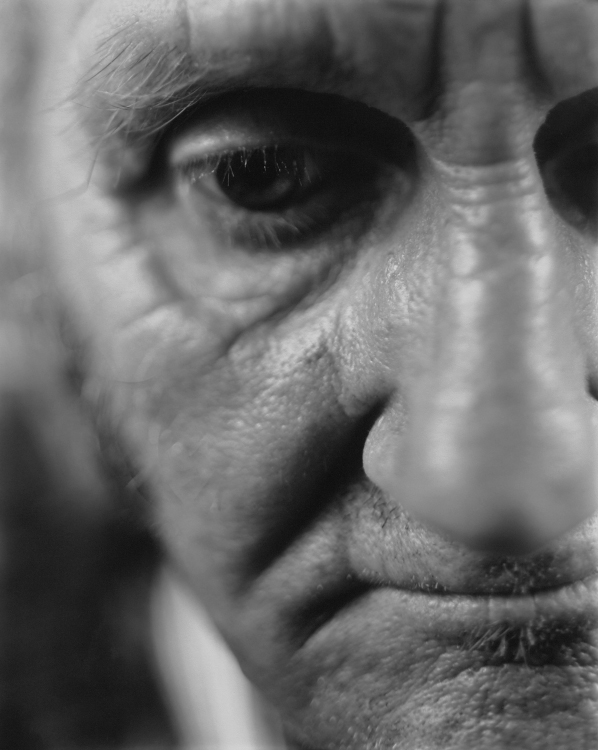

KEVIN CAPON Ralph Hotere 1985

Gold & selenium toned gelatin silver contact print, 195 x 245 mm.

Kevin Capon’s 1980s portraits of luminaries from New Zealand’s art scene are one of the most extraordinary achievements in the history of photography in New Zealand. Not because of whom he photographed — but because of the unorthodox, experimental way he approached the task.

A portrait is a collaboration in which the subject must let go, more or less, and trust the artist with a degree of intrusion into one’s personal space. It is a test of just how much scrutiny and intimacy one will allow. As familiar as the camera has become in modern life it is still a challenge for the portraitist to replace the self-conscious pose with a more open rapport.

In Capon’s case, the struggle he had, with the assistance of his wife, Carol Te Teira Capon, to set up a brute 8x10” studio camera and light his subjects sufficiently to see them on his ground-glass screen, elicited a remarkable degree of cooperation through which his subjects lost practically all sense of themselves as they pressed closer to the lens. Nobody could tell how they looked until the film was processed and they first saw the contact prints. His approach reminds me of a delightful 1885 Edward Payton drawing, Reciprocity, of a Maori woman peering so closely into Alfred Burton’s lens that it looks like she was intending a hongi.

Capon’s results were nothing like anything he had done before, nor anything their subjects expected. They were not flattering—the narrow plane of sharp focus specifically aimed at the eyes often picked up the lips as well, leaving the nose in his frontal views to appear as weightless as a floating balloon; the surgical skin detail was a revelation. Ron Brownson, curator at the Auckland Art Gallery, who sat for the series thought his portrait was ‘searing’, but acknowledged, ‘I looked like who I am.’

Other close-up portraits from the history of photography come to mind: among them Julia Margaret Cameron’s famous Victorian men; Edward Weston’s closest, most intimate portraits; Helmar Lerski’s theatrical heads; Bill Brandt’s artist’s eyes; Ken Ohara’s One—a dense catalogue of Japanese faces; the daring impolitenesses of Richard Avedon and Diane Arbus’ portraits; and Chuck Close’s confronting paintings and photographs. Although more modern and more jarring in style than Cameron’s, Capon’s head hunting retained the same kind of freshness, due to the adoption of ‘mistakes’ that teach us to see in a different way. Not all of his portraits are equal—some are more about photographic form than their nominal subject matter—but they all challenge our memory, emotions and imagination about people we likely know of, rather than know personally. Capon’s singular body of work continues to question and challenge a range of orthodoxies.

KEVIN CAPON Doris Lusk 1985

Gold & selenium toned gelatin silver contact print, 195 x 245 mm.

KEVIN CAPON Colin McCahon 1984

Gold & selenium toned gelatin silver contact print, 195 x 245 mm.

KEVIN CAPON Tony Fomison 1984

Gold & selenium toned gelatin silver contact print, 195 x 245 mm.

KEVIN CAPON Don Driver 1984

Gold & selenium toned gelatin silver contact print, 195 x 245 mm.