Exhibitions Wellington

STEVE ELLIS

Paul Hartigan's 'Picturesque': A Survey Show

If Paul Hartigan's Picturesque show was to be described in one word, I think that word would have to be 'oral'. Oral in two senses - the linguistic sense (words, hieroglyphs and calligraphy being important); and the Dali-esque 'gastro-aesthetic' sense (the world perceived through the mouth).

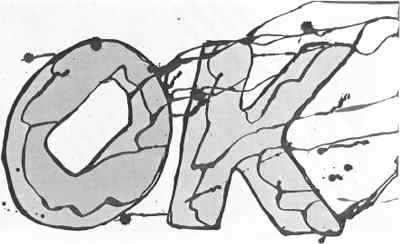

The linguistic aspect is fairly self-explanatory, as were the Hartigan pieces which suited this category: it is the oral quality of words (written, spoken or read) and of the word-images (hieroglyphs and calligraphy) associated with language. The Hartigan linguistic is strongly three-dimensional: words and symbols suspended against a flat or infinite backdrop. And the more explicit of Hartigan's word-image pieces (especially the drawings) have a strong link with graffiti. Twot, Pox and OK (all 1979 works) were idiosyncratic of this approach. Twot and OK were ink and watercolour drawings, hygienically dribbled (horizontally, or vertically in defiance of gravity); and the letter forms themselves were light, puffy and brightly-coloured.

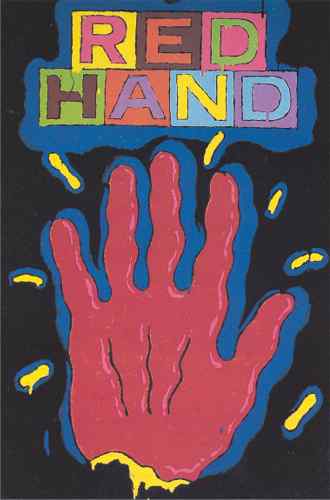

PAUL HARTIGAN

Red Hand 1978

enamel on board, 915 x 605 mm.

The dribble effect appeared in a number of works and was an effective device for avoiding stasis and two-dimensionality - as in Crossword which would have been quite flat and motionless had it not been for the dribbles in both black and white which ran from square to square. Crossword (1973) was an important piece as far as the linguistic orality was concerned. It was also a definitive work in terms of the show as a whole. Crossword was linguistic by omission: words (and strictly governed words at that) made powerful by their absence. The painting was a large and (apart from the dribbles) faithful reproduction of a standard newspaper crossword puzzle. I am sure that I was not the only viewer to wish there was a companion piece entitled Clues. I suppose that work could be called an example of 'negative linguistic orality'.

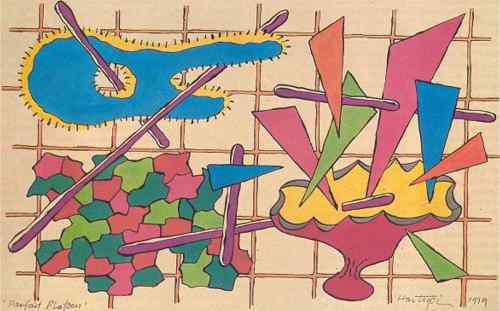

Red Hand was a link between the explicit linguistic pieces and the more sensual works; it also acted as a hinge between word images and hieroglyphs. The hieroglyphic pieces were generally drawings, colour or monochrome. Silly Eights (1979) and Primary School (1974) are fairly representative examples of the suspension against a backdrop mentioned earlier. Again the forms were puffy and partially eroded in appearance, like regurgitated marshmallow or half-cooked dough - although they occasionally appeared suspended against a hard-edged lattice or stick arrangement. The puffy or tactile effect of the forms in most of these works is a symptom of sensual orality.

PAUL HARTIGAN

Parfait Platoon 1979

indian ink and watercolour,

310 x 510 mm.

Sensual orality has its basis both in the history of twentieth century art and in the development of consciousness in any human individual. Freud, Jung and Piaget speak of the oral stage as an important one in the cognitive development of the child, and, although oral sensualism is repressed with age, it is a subconscious force which cannot fully be ignored. The oral stage is expressed by the child's desire to put all of his discoveries into his mouth - to use the lubricated palate and tongue to fully realise an object's three-dimensionality. The child educates the sensations of his mouth before those of his eyes and fingers. It was these sorts of forms which Hartigan put on show in Picturesque.

The historical basis for a pictorial orality can be found with both the Dada-ists and Salvador Dali. The Dada-ists spoke of 'art devouring itself' while Dali spoke of 'auto-cannibalistic art', a world in which consciousness comes only from eating and vice versa - living to eat as much as eating to live. There is this Dada/Pop sensation in much of Hartigan's work, which expresses the appetite rather than the act of devouring. The sensual orality, then, is a largely subconscious, repressed urge to experience with the mouth the world around us, and the 'pictorial orality' exploits that urge.

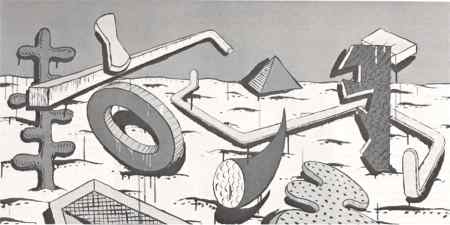

PAUL HARTIGAN

Landscape Number 1 1974

enamel on board,

608 x 1208 mm.

There were only four exclusively sensual works in the Picturesque show: four screenprints of nudes or semi-nudes entitled Gals and Gags (1973). The sensual orality overlaps eroticism, as could be expected; and Gals and Gags were handy parodies of a whole tradition of eroticism. They were photo-screen prints of what looked like strippers: photographs straight out of a girlie magazine executed in acid fluorescent colours. The colour of Gals and Gags was aggressive, enhancing the sensuality rather than compromising it. There is another overlap between the linguistic and the sensual oralities (especially as seen in Hartigan's work): many of the forms and devices used express both oralities although the accent varies. The large area of overlap contains the most effective works in that they employ both word-image and sensual device. Pox and Twot fall into the sensual category as well as the linguistic due to the form the letters take. They (like the forms in Landscape No. 1 1974) are the sort of concise closed volume that we imagine would be delightful if put in the mouth. Some are rectlinear, some puffy, some smooth, some textured: but they all have the same attraction as the little iced animal biscuits which sadly seem to have disappeared from the market. Little Lies and Treasure Chest were two more screenprints of an explicitly sensual nature. They both depicted false breasts deliciously realized in full three-dimensionality; again the eroticism, the hot bright colour and the desire to grab the object from its support.

New Zealand Breakfast was rather a renegade work. It was obviously oral (eggs on toast): and perhaps it was too explicit a realization of the oral impulse. Unlike nearly all the other works it was stylistically most in debt to the hard-edge realism approach to painting - although dribbles again intervened. The dribbles too are a part of the sensual orality, expressing (like most of Hartigan's work) the appetite or anticipation of oral experience. Like Pavlov's dogs it is as though the works themselves salivate and secrete juices in anticipation.

PAUL HARTIGAN

OK 1979

indian ink and watercolour,

340 x 510 mm.

Let us look at the more superficial (yet just as revealing) manifestations of Hartigan's work - specifically colour and line. Hartigan's colour is consistently flat, without modulation: which seems to compromise what has just been said about three-dimensionality. However, the way in which the colour is used ensures depth - for instance the use of complementaries in Landscape No.1 to create the third dimension, beyond considerations of line or drawing. In that respect the use of colour is formal: the intensity of that colour is not. Much of Hartigan's work has a pyrotechnic quality. All the colour is crisp and clean - aggressive but not violent. The intensity ranges from incandescence to fluorescence, from the bitter to the acid. Gold and silver also appear. Eternal Shoe (1973) was largely silver, but still entirely consistent with the use of colour elsewhere. None of the works on show used formal perspective. Space, where it was used, was infinite - the space being suggested by colour or by informal linear or compositional elements. The element of line is strong in Hartigan's work: it is a structural black web on which the fantasy is hung. The quality of the line varies, from spidery dribbles in ink to chunky brushstrokes in enamel as in Landscape No.1.

Picturesque was an effective show: one that, at its best, worked on a subconscious level. It was a teasing and suggestive show, half-mocking, half-suicidal, in the Pop/Dada manner - a show that posed and answered its own questions.