Frozen Flame & Slain Tree

The Dead Tree Theme in New Zealand Art of the Thirties and Forties

MICHAEL DUNN

Two pictures painted in New Zealand in the 'thirties and 'forties, Christopher Perkins's Frozen Flame (c1931) and Eric Lee-Johnson's The Slain Tree (1945), have in common the subject-matter of a dead tree.(1) Stylistic differences aside, both works deal with the trunk and branches of trees struck down by some man-made or natural calamity so severe that only the stoutest parts have survived as a skeletal reminder of their past existence. Deprived of organic life, these tree-forms appear gaunt and spare: yet far from lacking in vitality. Each twist and turn of branches is redolent of the forces of growth that shaped them. To the imaginative spectator, comparisons with human forms readily spring to mind.

Certainly, artists of the nineteen-thirties and 'forties were responsive to this particular subject. Painters as diverse as Gordon Walters, Rita Angus and Russell Clark made works featuring dead trees: as did John Holmwood and Mervyn Taylor, to mention only the better-known and most significant. Why was the subject so popular at that time? My aim is to examine some of the reasons by looking at the background of both artists and their works.

To begin with, it is important to realize that whole forests of native trees were being destroyed by the axe and by fire in the process of clearing the land for agriculture or sheep farming. Burn-offs of native bush were a common sight, for example, in the Auckland province of Lee-Johnson's boyhood. He recollects: 'My interest must have its roots in my frontier childhood, in the bush clearings at the time of the big bush fires'.(2) These fires, often on a huge scale, were spectacular affairs that drew the attention of visitors to the country. One such was the American writer, Zane Grey. He wrote in 1926: 'From Wellington to Auckland was a long ride of fifteen hours, twelve of which were daylight. The country we traversed had been cut and burned over, and reminded me of the lumbered districts of Washington and Oregon.'(3) later, he saw the effects of burn-offs at his base in the Bay of Islands: 'The music of the skybirds, the joy of life that they vented so freely, had been quenched by the fire, the creeping line of red, the blowing pall of smoke.'(4)

The result was a landscape strewn with black charred trunks, or white weathered branches. It was almost impossible to ignore this weird distortion of nature - a landscape of dead and mutilated remains of trees. Back from England in the nineteen-thirties, lee-Johnson saw the trees as a special landmark. He recalled: 'When, on my return in 1938, I saw the familiar forest ghosts lining my route up through the King Country, it seemed they had turned out to greet me.'(5) For Gordon Walters, then based in Wellington, the stark shapes of dead trees in a deserted burnt-off landscape had a comparable impact. He writes: ' . . . the trees, huge dead ones, were a prominent feature of North Island bush landscapes and one did not have to go far to be confronted with them.'(6)

Walters claims that the dead tree was a subject which had 'been ignored' by local artists until then. While this is not strictly true (there are examples in colonial art, such as James Crowe Richmond's Detribalised Natives of 1869), there had been no serious attention of the kind given in the nineteen-thirties and 'forties.

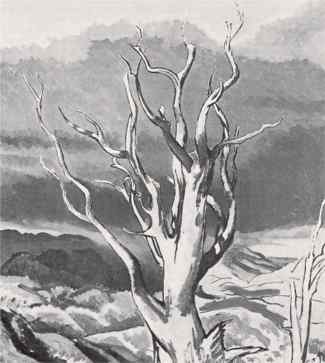

CHRISTOPHER PERKINS

Frozen Flame c1931

oil, 660 x 605 mm.

(Collection of the Auckland City Art Gallery)

A number of thematic and symbolic qualities attracted artists to the dead tree theme. In retrospect, the conservationist aspect (which now seems so important) appears to have played a small part in directing painters to the subject, since the need to conserve probably looked less urgent then than it does now. An awakening to this matter comes mainly in Lee-Johnson's work; and derives as much from his extensive coverage of dead tree subjects as from his presentation of them.

A work such as The Slain Tree 1945, appears relevant in this context. The former owner of the oil, Mr Terence Bond, was one of lee-Johnson's patrons in the mid-forties. He was an opponent of wholesale bush clearance for the grazing of land: with its sequel, soil erosion. Bond, a good talker, was knowledgeable and well-read on such matters. He bought K.B. Cumberland's Soil Erosion in New Zealand when it was published in 1944.(7) In this book Cumberland tried to draw the attention of laymen as well as geographers to the problem of the widespread soil damage arising from crude bush clearance. He included many photographs, often his own, with explanatory captions to clarify his viewpoint. Inspired by this book and his personal observations, Bond was sure to have talked to Lee-Johnson about such issues as soil erosion during their discussions in the Mahurangi hut, north of Auckland, where lee-Johnson was staying. Probably Bond helped form a consciousness in the painter's mind which then matured into an actively conservationist attitude to the native bush. But it would be misleading to exaggerate one level of meaning in the dead tree pictures.

Thematic meaning is not absent from Christopher Perkins's work either. However it is not simply a question of a conservationist stance. Certainly Perkins was well aware of the indigenous beauties of the country. He was equally aware of the growing local industries. After all, it was he who painted a modern dairy factory in front of Mount Egmont. Not surprisingly, Frozen Flame, in common with his other pictures of 1931, especially Taranaki (Auckland City Art Gallery) and Activity on the Wharf (present whereabouts unknown), has strong symbolism as well as a deliberate indication of a progression of events in a time sequence. Records of Perkins's artistic aims made by Professor Robertson in the early nineteen-thirties refer to his choice of imagery to imply the past, show the present, and indicate the future.(8) Frozen Flame, on analysis, conforms to this pattern exactly. It concerns not just the death of a tree, but the wider issue of the clearing of the bush for pastoral activity, in which the destruction of native trees is a necessary, if sad, event.

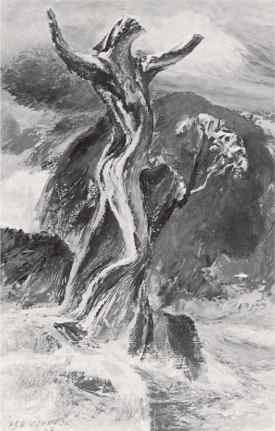

ERIC LEE-JOHNSON

The Slain Tree 1945

oil, 505 x 381 mm.

(Collection of T.T. Bond, Auckland)

Frozen Flame has some puzzling features - such as the sketchily-outlined hills to the right, or the large cloud behind the central tree. Some observers, misled by these factors, have argued that Perkins's picture was unfinished - this despite the incontrovertible signature 'C.P.', placed to the lower right. Why sign a painting if it is not finished to your satisfaction?(9)

If we examine each part of the picture as a planned coherent whole, difficulties such as these are removed. Perkins placed the tree near to the centre of his painting and drew it close up to the picture plane - so close in fact that its trunk is cut off by the frame. By outlining trunk and branches, as well as by focussing the highest lights on the dead tree, he made sure it was the pivotal image in his picture.

Its prominence, however, must not blind us to the presence of the smaller dead tree to the right: because it shows that the central tree is but one of many, the remains of bush. Perkins's dead tree stands between past and future. It is a reminder of the bush to which it once belonged. Its twisted frame, shorn of twigs and foliage, also implies the fire of bush burn-offs. Soon it will be displaced by the encroachment of pasture and sheep.

What of the background? On the right-hand side, Perkins has evoked the as yet unformed character of cleared bush land with a few undulating lines, evocative in pictorial terms of the shaping process to come. In the central background the dark cloud now has clear meaning. It is formed by the suffocatingly thick smoke from the burning of bush-covered hills extending as far as the horizon.(10) Its fumes hang heavily over the scorched slopes. Now Perkins's skilful juxtaposition of fire and its aftermath, the dead tree, gains intensity; cause and effect come together in telling fashion; to the left, bright green grass shows the final phase of the cycle.

Frozen Flame draws some of its power as an image from this distillation of ideas into one significant form. Perkins was not alone in such an approach at the time. For example, Roland Hipkins, in his picture Renaissance (Hawkes Bay Art Gallery, Napier), based on the earthquake-stricken Napier of the early nineteen-thirties, reveals a comparable interest in a symbolical, cyclical presentation.(11)

As we have suggested, Lee-Johnson's The Slain Tree also is symbolic. The idea of sacrifice is involved in its title and made insistent by the anthropomorphic allusions. In another well-known painting by Lee-Johnson, In the Backblocks (Auckland City Art Gallery), the artist isolated and emphasized the dead trees around the house. They become large unnaturalistic forms, almost imbued with a life due to the writhing movement of their trunks and branches. The trees are symbols of a frontier land still being broken in by man. One has not totally controlled the other. Here, the 'ghosts' of trees (to use the painter's phrase) still stalk the hillsides.

ALISON DUFF

Manaia 1954-55

kauri, life-size

(The Hocken Library)

(photograph by Steve Rumsey)

Compared with a nineteenth century watercolour of bush clearance near Inglewood, Taranaki, by John Kinder, In the Backblocks is not a reassuring picture of progress. Kinder's work (in the Auckland City Art Gallery), dated 1879, is almost idyllic. He records man's progressive clearance of gently-rolling slopes for pasture, the building of houses, and the felling of the dead burnt trees. This Lee-Johnson does not convey. His landscape is of rugged hill country where the trees are numerous and assertive. The house, too, is rough and makeshift. Here Kinder's colonial optimism gives way to a sterner reality. There is struggle. Nature, perhaps, has the upper hand. And the painter draws the trees as big forms: still, even in death, holding fast to the land. To Kinder, the dead trees are an incidental part of the landscape, a sign of an old order giving way to a new, more desirable one. That was very much a typical view in colonial times. By the nineteen-thirties and 'forties such an outlook was no longer universal.

The imagery of dead trees and bush fires is shared with the painters by the New Zealand poets. Blanche Baughan and William Pember Reeves, for example, had chosen the landscape of dead trees as symbol of a transitional phase in the development of the country.(12) Blanche Baughan's poem, Bush Section, uses the main images of fire and dead trees plus , . . . The little raw farm on the edge of the desolate hillside. . . ' - which brings to mind Lee-Johnson more than Kinder. She looks forward to the time when' . . . the charr'd logs vanish away. Till the wounds of the land are whole. . . '. She seems to recoil from the grim landscape. Her line, , . . . Tis a silent skeleton world' suggests some response, though, to the qualities that we find painters of the nineteen-thirties and 'forties evoking.

William Pember Reeves's position in his poem The Passing of the Forest is unequivocal. He laments the destruction of the bush. For him the process is ' . . . a bitter price to pay for man's dominion - beauty swept away'. His references to 'The Fire's black smirch, the landslip's gaping wound' are strongly critical. His concern for the native forest and wild life is genuine and perceptive. It precedes by some forty years the strong statements of Cumberland in his publication on soil erosion, where similar sentiments gain the backing of scientific documentation and analysis.

A.N. BRECKER

Burnt Bush

(The Auckland Institute and Museum)

Alan Mulgan, in his poem Dead Timber, published in the mid-twenties, continues the theme.(13) Like Baughan and Reeves, he sees the dead trees as ' . . . the desolation of our making', a necessary stage in the growth of European settlement. But, to him, in a country devoid of the marks of Old World civilization (such as the temples of Greece or the minarets of Turkey), the dead trees take on a monumental and symbolical importance. They are symbolical because they stand for the transition from wilderness to cultivated countryside: yet, more, as local equivalents for an architectural heritage. He writes: 'There, on the hillside, is our nation's building, the tall dead trees so bare against the sky'. To those who ask: 'Where is your art, your writing. . . ' Mulgan offers the reply: 'Yonder the hillcrest blighting. There is our architecture's blazoned way'. Curiously, Mulgan here anticipates one aspect of the painter's vision - seeing the shapes of the trees as art works waiting for the right sensibility. In his case the idea is mainly rhetorical. He makes it quite plain that he looks forward to a time when 'dwellings rich and olden', as he phrases it, will replace such makeshift monuments as dead trees. No more than Baughan or Reeves does Mulgan really share the painters' sensitivity to the concrete imagery of the dead trees; though these writers do anticipate the thematic and symbolic ideas discussed so far.

Of those painters influenced by Lee-Johnson, it was Russell Clark who added a further symbolic dimension to the dead tree subject. Among his series of Maori paintings we find a few examples, such as his pen and wash study, In the Urewera, 1957 (private collection, Auckland), where Maori figures are introduced into a landscape dotted with dead trees.(14) This juxtaposition provides a new set of associations with a degree of poignancy. The studies were first made in the Urewera region, the tribal lands of the Tuhoe people for whom Clark developed a great admiration. He wrote of their sense of tradition, of their closeness to the land. But he was too much of a realist to be blind to the changing pattern of their life-style, increasingly subject to European ways.(15)

The gaunt tree trunks speak eloquently enough of the clearing of tribal land and of the growth of Western agriculture. In fact, they gain meaning as symbols of the situation of the Tuhoe Maori. The trees burnt-out and deprived of their traditional habitat must die. Yet they cling on in a kind of half-life to the land as if reluctant to go away. By bringing the Tuhoe people into this landscape caught between past and future Clark adds to the slain tree a new meaning as a symbol of the old time Maori people and their lifestyle. And aptly too: for Maori ancestors were carved into such trees and placed in meeting-houses for the instruction of the young in their traditions. This reflective overtone is in keeping with Clark's Old Keta, 1949 (National Gallery, Wellington), and the Urewera series as a whole.

Interestingly, the connection I have established here has an extension in a work by the sculptress Alison Duff. Her large wood carving, Manaia, 1954, (the artist's collection, Auckland), was worked out of a Kauri stump she recovered from a swamp near her home. Aware of the sacred role such trees had in Maori times, she attempted to restore in her carving something of the lost power of 'mana' of the tree attributed to it by Maori tradition. Her loving restoration of surface to the timber, her careful shaping, can be seen as an almost ritualistic reversal of the path of destruction we have traced so far. Instead of ravaging the land, she provides an ecological healing service to restore the tree to new life by evoking traditional Maori values associated with the giant trees of the native forest. The Maori balance between forest and use is recalled as a guideline for the present.(16)

In both Perkins's Frozen Flame and Nash's We are making a New World, flattened, simplified drawing with outlining is very apparent. So, too, is the symbolic quality of the imagery. Even the colouring is related less to representation than to the pictorial structure and theme. For example: in Nash's picture the blood red sky behind the trees is purposely exaggerated, just as the smoke pall in Perkins's work is made ominously dark and oppressive. Theorists of the time would have fully condoned this degree of alteration' of natural appearances. Roger Fry, for instance, encouraged the study of previously-neglected primitive art, in which representational qualities were unimportant. Elements of a picture, such as colour and line, were to be considered independently of naturalistic meaning. Perkins's own art writings are in the same vein. He made disparaging remarks about 'windows on strings' in an article for the quarterly Art in New Zealand. (19)

Owing in part to this concentration on formal values, the found object becomes of fresh artistic importance. Not only Paul Nash, but associates like Henry Moore, began to collect natural objects for study. Apart from drawing and painting them, artists turned increasingly to another method of recording and interpreting such objects - the photograph. Nash, in particular, has recently won recognition as a photographer independently of his reputation as a painter. Among his published photographs (shown in the Tate Gallery exhibition Document and Image) are many of the type celebrating the object.(20) There are close-up studies of pebbles; a part of a haystack; part of a tree trunk stressing the bark patterns; and several of dead trees. In one of these, Dead Tree, Romney Marsh (No.91), Nash focuses sharply on part of a dead tree trunk and branches. By cropping off the branches and bleaching out the background, Nash isolates the textures and patterns for our special consideration. His interests are in the pattern of the cracked, dry timber; the silhouetted shapes and the subtle pattern of light and dark. These completely overshadow the photograph's value as a record of a specific tree.

PAUL NASH

We are making a New World 1918

oil

(Imperial War Museum, London)

Gordon Walters and Eric Lee-Johnson also took photographs of natural objects at the time they were painting their dead tree pictures. Walters made studies of dead trees near Waikanae Beach in about 1943, using a camera borrowed from Theo Schoon.(21) Like Nash, he came up close to his subjects. He photographed trunks, textured bark, twisted jagged branches. He took not one shot but a series. He studied how different views or angles changed the form or gave new shapes against the sky. Also like Nash, Walters studied the patterns of stones lying on the beach, as well as the rhythmic lines etched in the sand by the wind. Walters knew of some Nash photographs. Significantly, he had also seen the Museum of Modern Art publication on Weston, the noted American photographer, whose works featured similar subjects, including dead trees.(22)

The symbolic potential of the dead tree in New Zealand could hardly escape painters who were looking for some qualities in their work to give it a national character. For Lee-Johnson, the Auckland landscape (not only the trees but also the colonial wooden housing made from them) had a distinctive appearance which struck him forcibly on his return from London. Like Perkins (who wanted local artists to turn to indigenous subjects) Lee-Johnson hoped to gain some distinctive imagery from regional subject matter. This was hardly the major concern. It was a minor one, intrinsically tied up with stylistic matters, also of contemporary concern in Australia. It was natural enough about the time of New Zealand's Centennial in 1940 that reflections on a national identity in the arts should occur and be integrated into a painter's consciousness. But this regional problem of identity coincided directly with the questioning of representational art itself - no matter how much it might be adapted to local conditions. And the movement into non-figurative painting, soon to follow, was less amenable to regionalist solutions.

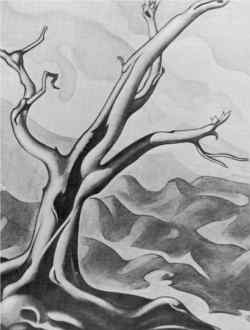

It is noteworthy that these pictures were made at the very time of serious questioning of priorities amongst British artists. In Perkins's Frozen Flame there is much emphasis on the formal 'elements (such as the outlining of the tree, which is highly abstracted). Similar concerns in Gordon Walters' work were to lead on, more or less step by step, to nonfigurative painting in the late 'forties. In his Waikanae Landscape 1945 (G.H. Brown Collection, Auckland: See Art New Zealand No.9 page 59) Walters has already changed natural space and form to make his own images of self-determining meaning.(17) And here, precisely, is the irony. What has sometimes been thought of as a bland illustrative art was initially something of quite different substance. Even lee-Johnson evolved a non-figurative style in the nineteen-fifties.

GORDON WALTERS

Composition Waikanae 1943

conté drawing

The focus on dead trees in New Zealand painting between the wars owes much to developments in European art after Cubism. Frozen Flame is one of the first New Zealand pictures of the type. It is not pure coincidence that its painter, Perkins, was an English artist who was well aware of the latest trends in European paintings. One of the artists he knew was Paul Nash, with whom he exhibited on several occasions. During the Great War, Nash as official war artist painted a small oil, We are making a New World, 1918, now in the Imperial War Musuem, London.(18) Even today it sums up the pervasive wreckage of total war better than any other of his works. In this picture no humans suffer or die. Rather, the work gains intensity from their absence. It has the same emptiness we find in many of the New Zealand dead tree pictures. Trees form the central images of Nash's painting. Not trees in their full glory: rather the shattered remains of them - mere trunks with ragged tops and edges stripped of bark.

At this time, many in New Zealand art circles frowned on the use of the camera. Lee-Johnson found it best not to publicize his extensive photographic practice, and so did Walters. Lee-Johnson had learnt photography while he was a commercial artist in London. Back in New Zealand, he found his skill with the camera helped supplement the meagre income he made as a painter. Most of his photographs were taken as independent works, not as mere aids to painting. In the case of The Slain Tree, there is a close correspondence between photograph and painting. Both Walters and Lee-Johnson made drawings as well as photographs in their working process. Walters's tree paintings of the early 'forties pre-date those of Lee-Johnson slightly - and there was no connection between the artists. In fact, Lee-Johnson knew nothing of Walters's efforts, or of Perkins's works.(23) Walters, however, did see Lee-Johnson's published pictures in the 'forties, after he had dispensed with comparable subject matter. Walters had moved to near-abstraction by 1947, when he was most involved with problems set by Paul Klee and those suggested by Maori rock drawing.

To some extent (especially in the works of Walters and Lee-Johnson) there is a mild reflection of Surrealist ideas. The passage of such conceptions to New Zealand was spasmodic: but definitely a fact by the years of the Second World War. Apart from magazines, there were a few books and reproductions to provide guidelines. For an artist with sympathy for the surreal, the dead trees with their rich host of suggestive associations seemed a good starting point. (In fact, tree forms supplied Max Ernst with the basic imagery of his mysterious forest paintings of the 'twenties, such as The Great Forest, 1927, Basle, Kunstmuseum.)

The strongest link comes in Walters's conte drawings. In a work like Composition, Waikanae, 1943, (present whereabouts unknown), the entwined tree forms become as seemingly soft and pliable as a Dali watch. Walters places them on a deep space plane which stretches back to a distant horizon, again bringing to mind Dali and the European Surrealists including Yves Tanguy. Tanguy seems especially important for the Waikanae Landscape, 1945. Here the trees are simplified to cylindrical shapes of excessively harsh contour. Again the space plane is exaggerated and disconnected judged by naturalistic stardards.

Lee-Johnson's The Slain Tree has a comparable strangeness. It is an objet trouvé, isolated and stage-managed to have several layers of meaning. Actually it is less descriptive than most of the artist's later pictures of similar subjects. It is impossible to ignore the association with a human form - equally impossible to ignore the fact that the tree had been alive. Lee-Johnson had found the tree and photographed it because of its puzzling ambiguity. The Slain Tree is comparable with Paul Nash's fallen elm trees in his photographs and paintings of 1939-40.(24) For Nash the dead trees had an 'animal quality', and appeared to stand on legs made of broken branches. As in Lee-Johnson's work, the tree figuring most in the so-called 'Monster Field' is astride its broken base. This acts in both cases to lift the anthropomorphic part off the ground and help to endow it with associations of movement.

RUSSELL CLARK

In the Urewera 1857

pen & ink with red & black wash,

280 x 380 mm.

(private collection, Auckland)

The notion of life suggested by an inanimate object had a vogue in Britain during the nineteen-thirties and 'forties. Not only painters, but sculptors, too, made a special study of stones, driftwood, dead trees and such-like objects. In the grain of branches, the strata of rocks, the hollowings of pebbles worn by the tide, were found the evidence of this vitality. These inanimate objects provided visual metaphors of organic life. An adroit selection of natural objects which were specially conducive to such associations helped overcome the dangers of imitation, and fitted, at the same time, with the popular Surrealist aesthetic.(25)

By the early 'fifties most of the artistic potential of the dead tree subject for painting and photography had been exhausted. The scope of trees and branches, of driftwood and pebbles, proved to be limited. Then came the degeneration to pleasant but less important statements. These include Mervyn Taylor's trees in half-broken-in farmland and John Holmwood's saw-mills. Soon the dead tree was synonymous with a dead end in New Zealand art.

The dead tree theme in New Zealand art was at once symptomatic of a regional awareness and of an international trend in painting, sculpture and photography. The connections in terms of movements were with Surrealism, Vitalism, and, curiously enough, with abstraction. In conclusion, it is worth mentioning that Australian artists also made a number of works based on this theme, for much the same reasons as their New Zealand counterparts, but without quite the same identification with it as a distinctive regional symbol.(26)

1. For the best discussion of Frozen Flame see the unpublished thesis by E.M. Lawton, 'Christopher Perkins: The New Zealand Years', Auckland University, 1975, pp. 39-40. For The Slain Tree, see E.H. McCormick, Eric Lee-Johnson, Hamilton, 1956, p.26; also The Arts in New Zealand (Wellington), 1-5, pp. 39-41

2. E. Lee-Johnson to author, 6-12-1976.

3. Zane Grey, Tales of the Fisherman's Eldorado: New Zealand, London, 1926, p.24.

4. ibid p.79.

5. Arts Yearbook, Wellington, 1947, p.29.

6. G. Walters to author, 7-11-1976.

7. I am grateful to Mr Bond for having spared the time to talk to me about this period. See K. T. Cumberland Soil Erosion in New Zealand: A Geographical Reconnaissance. Wellington, 1944.

8. See P.W. Robertson, 'The Art of Christopher Perkins', Art in New Zealand, No. 13, Sept. 1931,pp. 9-22. Lawton, op. cit. p.40.

9. Lawton, op. cit., p.40.

10. Lawton's reference to a 'high bank of cloud' does not suffice to explain Perkins's meaning. See Lawton, ibid. p.40.

11. See G.H. Brown, New Zealand Painting 1929-40: Adaptation and Nationalism. Wellington, 1975, p.38.v

12. See B.E. Baughan. 'A Bush Section' in Shingle-Short and Other Verses. Christchurch, 1908, pp.79-88; also her 'Burnt Bush' ibid. For W.P. Reeves see The Passing of the Forest. London, 1925.

13. Alan Mulgan, 'Dead Timber', in The English of the Line and other Verses. Christchurch, 1925, pp. 13-14.

14. See M. Dunn, The Drawings of Russell Clark: New Zealand Artist and Illustrator, Auckland, 1976, plate 51.

15. R. Clark to Mrs Goodger, 2-5-1957. Letter in Auckland War Memorial Museum Library.

16. Statement by the artist, New Vision Gallery, Auckland.

17. Waikanae Landscape, black conté, belongs to a group of undated works done c. 1943-45, but is close to the end of the series.

18. First exhibited 1918, London.

19. C. Perkins, 'Arrival', Art in New Zealand, No.5, 1929 pp. 15-16.

20. Andrew Causey, Paul Nash's Photographs: Document and Image London, 1973.

21. Some of Gordon Walters's negatives survive and are in the artist's possession. lee-Johnson, unfortunately no longer has the negative of The Slain Tree.

22. Gordon Walters to author, 7-11-1976 23. lee-Johnson to author, 6-12-1976.

24. See Andrew Causey, Paul Nash: Paintings and Watercolours, London, 1975, p. 91; also pp. 74-75 for the oil February with the symbolic cutting knife in a tree stump.

25. For a good discussion see Jack Burnham, Beyond Modern Sculpture. Harmondsworth, 1969, pp. 65-109, with bibliography.

26. E. Lee-Johnson and G. Walters, as well as Alison Duff, were well aware of developments in Australian art of the nineteen-forties, as was Russell Clark. WaIters and Duff went to Sydney during that decade. Lee-Johnson was invited to exhibit in Sydney by S. Nolan.

This article was based on a lecture delivered by Michael Dunn at the Waikato Art Museum, as the Canaday lecture on the Arts for 1977.