about et al.'s abnormal mass delusions?

WYSTAN CURNOW

This could be the best exhibition of 2003. All right, I am writing this in the first week of 2004 and the season for making 'Best of' lists (in lieu of having anything better to say or think) is still with us. And I didn't see all the exhibitions, but in my book anyway, I want to say this was the best looking, most compelling show I saw all year. I didn't expect to be that affected, nor to be affected in the way I was, so that is one measure of its value for me: the surprise value.

et al., Restricted Access (2003) at abnormal mass delusions?, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, July 2003

Retrospective, although mostly from the last 12 years or so (Merylyn Tweedie began exhibiting in 1975), much of the work was familiar from earlier shows and screenings, and highly regarded by widely respected critics and curators, so you could say there was no reason to be surprised. Yet retrospectives do that, they can be make or break events, which is why artists secretly fear them, and why I set out for New Plymouth expecting revelations, but of what? New Plymouth? Is it likely that the best show of 2003 was to be seen at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery? And only there? Well, yes, actually.

Abnormal mass delusions? surveys the work of et al., a pseudonym for the large cast of pseudonyms assumed by Merylyn Tweedie, whose name appears only once in the accompanying publication, even in its exhibition chronology. These include Lillian Budd, Merit Gröting, P. Mule, Blanche Ready-made and others equally ridiculous. Now that I write it, Merylyn Tweedie, with its pairs of rhyming vowels, sounds just as fictional as the rest. I am sure this is rather confusing to first-time viewers; however, the curators and the Gallery remain unconcerned; they are in on the joke, and the publication wilfully collaborates in the pretence that this is a group show. Of course, it is not. Although the joke has always seemed rather feeble to me, and I dislike lies, one of my surprises at the show was to discover how little it matters that this was so. But more of this later.

et al., Restricted Access (2003) at abnormal mass delusions?, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, July 2003

These days et al. shows installations; back in the 1970s when she started out it was photographs, in the '80s she shifted to collages, mostly of xeroxed texts, and junkshop sculpture, combinations of the two, and films. But abnormal mass delusions? is not concerned with fleshing out the story of the development of her career, isolating and characterising the major works or concerns. It is not that kind of survey. Indeed, the secret to its success lies in its disdain for such clarifications. A disdain arising from a realisation that they may be at cross purposes with an art which has doubts about the autonomy of the individual work and erects recycling and revision into essential creative principles. But also, one must presume, from an understandable and commonplace desire to frame past practice in terms of the present. And this will work out if the recent work is as good if not better than the preceding work - good or better as demonstrated by its relation to the economy of the oeuvre itself. And it does work out. The decision of the curators, Jim and Mary Barr, Gregory Burke and the artist, to present the show itself as a mega-installation (or series of them), treating past work as its material, was bold and successful. As a converted cinema, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery consists of a series of levels linked by stairways rather than rooms linked by doorways. The exterior frame of the installation as a whole was established by painting most of the walls to above-head-height a uniform grey, while various internal divisions were constructed by the use of hurricane fencing. This has a powerful effect on the viewer's experience; it is as though there had been some mistake, and you have pushed the button in the lift and ended up in the basement. Somewhere where you are not supposed to be. Where no one belongs, except caretakers or other authorised persons. Where supplies, files are stored, locked up, where stuff is chucked out, left to gather dust, rot, etc. Or something worse, where the organisation's unofficial experiments/interrogations take place So all these levels, the upper floors, are in a sense brought down to one, and it is not A Clean Well-lighted Place - there once was a gallery in Texas of that name - one which is beneath the dignity of a public art institution, dragging it and its viewers down to its own level and into disrepute you might say.

et al., Restricted Access (2003) at abnormal mass delusions?, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, July 2003

So while abnormal mass delusions? re-works et al.'s past work into the present structure of a new installation it contains nothing that is new. For et al.'s art materials are in any case old objects, materials, texts and images. Disused, broken, out-of-date, soiled, damaged, rejected. They occupy as I say, space that seldom sees the light of day, and its shiny goods and services, yet the uses to which they are put imply a life of sorts is being led or constructed here, one that strangely enough is not as circumscribed by its conditions as you might think. Some ingenious repairs have been effected, the power has been connected, and some work is in progress. . . studies, investigations are being undertaken, arguments developed, devices are being constructed, quite unofficially you understand, but concerned with some pretty big questions, metaphysical, ideological, existential.

Abnormal mass delusions? is divided into five main sections, each of which is distinguished as much by its mode of address to the viewer as by the works / materials it contains. Allan Smith described it as 'operatic in terms of scale, complexity and orchestration of affect.'(1) As you enter the exhibition you are offered entry to two clearly contrasted installations. The gallery on your left presents itself as a storage area; behind hurricane fencing works are stacked with what I am told were the et al. contents of the stock rooms of her Christchurch, Wellington and Auckland dealers - part of which doubles as a studio / study, for at one end there was a table and chair, a naked light bulb, a jacket draped and signs of work. The area is poorly lit, and the viewer is left to peer through the wire at stacks of old books, suitcases; boxes full of rolled text works, old blinds, monitors and so on, and to wonder what if any sense of et al.'s oeuvre is to be gained this way. If this installation is somewhat reminiscent of Greer Twiss's replication of his studio in his recent retrospective, any suggestion that et al. is hereby making a fetish of her art or her creative processes is not so much dismissed as derided by the awful sound of a braying donkey - would that be P. Mule, by any chance? - which regularly punctuates its silence.

The gallery opposite it on the right contained two recent installations, whilst attempting to engineer a telepathic device and simultaneous invalidations: second attempt, each of which consisted of dispersed wall and floor elements among which the viewer was at liberty, not to say encouraged, to move freely. The openness of both works was both physical and conceptual, as their titles suggested, and at odds with the installation opposite. The first of these contained a scatter of small speakers around which a strangely entrancing music moved as though to partner the viewer's progress in and around it.

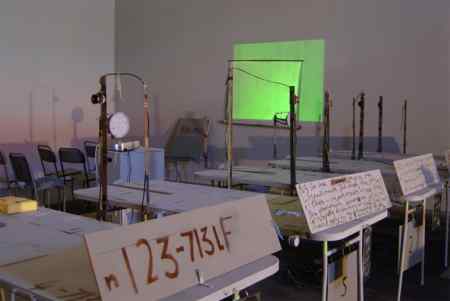

et al., serial reform_713 L (2003) at abnormal mass delusions?, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, July 2003

At the top of the main flight of stairs the gallery was almost entirely covered by a low platform, just high enough to deter the viewer from walking on it. In this way it distanced viewers from the works displayed. These were dispersed across its surface and hung on the back wall; they constituted a survey of what might be called et al.'s object works, various sculptural pieces, mainly items of domestic or office furniture and, on the walls, several of the earlier xeroxed wall pieces, accompanied by light fittings etc. These evoked not so much the basement-like spaces of industrial, commercial or institutional buildings, as those of the suburban home. The third level comprised an installation for viewing a survey of et al.'s film and video works, including a video projections booth, a video sculpture and six viewing booths constructed from metal tubing and hurricane fencing, each containing a chair and a small monitor.

And the final level housed et al.'s most recent installation, serial reform_713L, a kind of classroom space dedicated to the delivery of some strangely abstract and obscurely sinister curriculum. Although I felt free to sit in the viewing booths, I did not think to take a seat in the classroom, to be a student. Almost all the installations included chairs, mostly empty, but in no instance was the implied protocol the same. In an interview, the artist asked: 'How do you make an object among objects that can somehow convey the feeling of Being - for the viewer?' In this regard the chair is an exemplary object. You wonder whether to sit on it, you wonder who it is meant for, who sat there doing what. Because of the old instrument cases and the arrangement of the chairs in attempting to engineer a telegraphic device, I imagined a musical group, and the taped sound from the speakers as the 'second attempt'. The manner in which the chair is for the viewer changes all the time, and it is never just for the viewer alone, but for viewers in the social and cultural circumstance of the installation and the exhibition as a whole. Proceeding from one level to another, from one installation to the next, you encountered a series of quite different sets of appeals and refusals, of cues which shaped the contours of affect which constituted your response.

Viewing booths at abnormal mass delusions?, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, July 2003

The grim, alienated materials and spaces that comprise et al.'s installations, the erasures, the blurring, fragmenting, of image, sound and textual content, speak of a comprehensive negativity. This work does not propose another world, life, society - because it can't - so much as the negation of the one that we have, the view from the Basement, from the situation of its negative Other. Normal, or abnormal mass delusions? Take your pick. Which is to say emptiness and obscurity here is limited by the fact that the Other always carries with it the mark of its opposite. Et al. undertakes o studies, however, implying that maybe there is more to be said for nothing than meets the eye. Something other than simple negativity, even something positive. . . . For example, when there is little or nothing to look at, our attention is drawn to looking itself and more particularly to the question of how the materials and the situation of the work are 'for' us in our viewing of them. In these circumstances content begins to build up again around the recognition of the work's affect. Responding to an Allan Smith comment linking video static and the blur of rubbed-out chalk writing, to the fuzzy droning of her sonic textures, et al. begins to discuss the constructive functions of these negatives:

Yes, noise invariably defines a space or a place which is different than that made by language or text. We see the work as creating a potential moment of engagement, be it external or internal dialogue. These moments of subjectivity and reaction are what create social discourse.' (2)

et al., whilst attempting to engineer a telepathic device (2000) at abnormal mass delusions?, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, July 2003

Abnormal mass delusions? was accompanied by the publication, arguments for immortality. Apart from the design which could hardly be more faithful to the et al. look, it is something of a disappointment. Partly, as I say, because of its fibs, and the way it goes on about 'the death of the author', when the work is much more a demonstration of the birth of the viewer. Partly because it is not a catalogue in the strict sense; without a list of works it can hardly be said to document the exhibition.(3) But mainly because the essays are so pre-occupied with their own mass delusions that they tell us less and less about the work the more we read. Writing before most of the work in the show was made, Robert Leonard claims that Merylyn Tweedie's art was 'deeply anti-intellectual' and that it 'asserted the resistant power of sensibility.'(4) I would not be surprised if he would like, as I would, to seriously modify the terms here in the light of the artist's subsequent and remarkable achievement; nevertheless, the claim is still worth considering given the relentless intellectuality and bookish theorising that dominates arguments for immortality. It reads as a defence which the work no longer needs.

1. 'Allan Smith talks to P. Mule for et al.' in Nine Lives: The 2003 Chartwell Exhibition, Auckland Art Gallery, Auckland 2003, p. 6. 2. ibid, p. 6. 3. It may be argued that to provide a list is to undermine the exhibition as a re-cycling of old works. But how is the viewer to know the work has a history at all? 4. Robert Leonard, 'Mixed Emotions', in Pleasure and Dangers, eds. Trish Clark and Wystan Curnow, Auckland, Moet et Chandon/ Longman Paul, Auckland 1991, p. 169.