Taking Flight

The Airborne and Hybrid Images of Joanna Braithwaite

LISA BEAVEN

Poetry and art move from where one is to somewhere else. One has to be airborne to succeed with either. ROSALIE GASCOIGNE (1)

A horizontal figure covered in a dense carpet of bees lies suspended in mid-air, against a blue sky, streaked with clouds. Single bees hover or detach themselves from the mass, in some areas exposing flesh, and the pale, still features of a face. The crawling mass of black and yellow is interrupted by the occasional white shimmer of wings. The psychological power of Bee Being (1999) derives from the associations with which the insects are weighted, and the strange mummified appearance of the recumbent body. It combines a spiritually uplifting effect with acute unease at the sight of bees swarming on a human body and the threat of their sting. It is an image of transport, both in the action of conveying a person or thing from one place to another, and in the sense of being 'carried out of oneself'. This mass of winged insects giving flight to a human raises one of the central themes in Braithwaite's art: the interaction of animal or insect with people in ways that are often threatening and that almost always represent an inversion of established power relationships. As she has written of these paintings: I decided to push this idea of an imbalance of power between man and beast further by considering the attributes of each. What if the balance was altered, and what if one species acquired some attribute of the other? I chose to paint a series of works where the human form was completely covered in creatures that could fly.

The bees have caused the body to leave the ground and become airborne, and the small darting sense of movement of individual insects in flight is contrasted with the mass and volume of the figure, suspended in mid-air. In other paintings, such as Hover (2000), or Resting Space (2001), a painting from her latest Auckland exhibition, this role is performed by clouds of vividly coloured, transplendent butterflies. Hover reveals a figure covered in a bright, shifting mass of dark blue, light blue and black that resolves itself into individual butterflies that have alighted on the body. The shifts in colour and texture evoke beating wings and a sense of fluttering, ceaseless motion. Butterflies cover every part of the body but the face and hands. Resting Space conveys an even stronger sense of vivid colour, as a flock of bright orange monarch butterflies gather on another suspended body, their individual markings of white dots on black borders clearly visible. In these works the colour itself seems symbolic of an exalted state of being, of a soaring beyond ordinary bounds. The careful and meticulous brushwork and the artist's virtuosity in painting individual butterflies and in conveying their textures all serve to persuade us of the reality of what we see yet simultaneously we are aware of a paradox: of the impossibility of the fragile, feather-light butterflies giving flight to the weighty human figures. In Butterfly Being, a figure seen vertically gazes upwards as it is raised heavenwards by a cloud of blue butterflies, an image that closely parallels Baroque images of saints ascending to heaven. The awareness of inner rapture and of being raised to a higher spiritual plane while leaving an earth-bound body is common to both.

With their glowing colours and meticulously painted surfaces these works are as luxuriant as they are disquieting. The intervention of the insects has brought about an altered state in the human being that they have clothed but the uncertain nature of that transformation provokes anxiety. The still, passive forms with closed eyes and pale features suggest morbid states. If not dead, these bodies are characterised by a lack of consciousness, or a trance-like state. They are disturbing because in each case they have implicitly surrendered to an unknowable other. They have given themselves to the insects who have taken possession of them, displaying a mysterious inner purpose. Could this condition be ecstatic? Ecstasy is a state of rapture in which the body is incapable of sensation, while the soul is engaged in the contemplation of divine things. Instead of divine intervention, though, this state of being has been brought about by the intervention of insects, who have mastery of them.

The placement of humans and creatures in mid-air, either ascending, floating, or falling, deliberately deprives the viewer of reference points. It is an idea with which Braithwaite has experimented since the 1980s, when she painted a series of sheep falling through the air, a theme prompted by seeing dead sheep thrown off the cliffs of the family farm near Dunedin. Recently she has painted people falling in the same way, limbs hopelessly jumbled, deprived of dignity and control. One of the flight paintings also shows a person plunging earthwards, upside down, covered in white butterflies. Here there is no sense of the balance of the other works of the series, just an extreme sense of awkwardness and dizzying speed. Mysteriously in this instance the butterflies have failed to keep the figure airborne. In her show, Phenomenon (1999) Braithwaite played with the idea of using animals as metaphors for the weather. In one painting, Frog Rain, the sky rains frogs, based on a reported incident: In one particular book I came across the phenomenon of frog rain. In 1902 in the West midlands of England Gertrude Griffin witnessed frogs falling out of the sky while out walking with her mother.

Frog Rain also carries ecological connotations, since frogs are the most sensitive barometers of environmental damage, and are the first creatures to disappear when an ecosystem is disrupted or polluted.

JOANNA BRAITHWAITE Paintings from the Menagerie series 2001 Oil on canvas, 150 x 180 mm. each

Braithwaite's interest in insects began with a series of works based on flies, which were designed both to unsettle the viewer and to question our assumptions that certain animals or insects were more worthy of our attention and respect than others. They are reminders of how arbitrarily humans have categorised animals and insects, and how they have valued them according to their own preconceptions. Braithwaite's fly paintings are deliberately seductive, lush pictorial images that challenge the repulsive reaction most people have to them. They were combined with images designed to trigger an uncomfortable response from the viewer: flies flying into open mouths, or uncomfortably close to vulnerable human orifices. In one image, wasps mass just under a pair of nostrils.

Braithwaite has been interested in exploring exchanges between people and animals since studying at the School of Fine Arts, in Canterbury in the mid-1980s. In her early work she concentrated on the discarded parts of animals as a way of exposing the underbelly of everyday life. This interest grew out of her farming background and was reinforced by her seeing the discarded limbs of a variety of animals in the scrap-bins outside a taxidermist's shop in a building below her workplace. The most memorable of the works she produced at this time was a series of monumental paintings of severed sheeps' heads, whose sheer scale and painterly qualities give them extraordinary power and poignancy. They were exhibited next to precisely rendered still-lives of chops, underlying the link between the dead animal and the product we eat. Much of Braithwaite's works are thus designed to make us confront realities we would rather ignore, and the unflinching depiction of those realities creates a tension in her work that is reminiscent of the shock tactics of artists such as Damien Hirst.

While living in the bush near Melbourne in 1992 Braithwaite began painting animal hierarchies, animals balanced on other rows of animals, including extinct species, such as the moa. Her interest in extinct species lay in society's perceptions of them, and the retrospective symbolic value granted them. She became interested in evolutionary theories and explored the implications of cloning animals, as in Three Heads Good, the representation of a three-headed sheep which makes an ironic comment on the quest to create a smarter sheep. Animals provide us with scientific subjects that we can watch and test, ostensibly without it mattering if it goes wrong. Braithwaite shows us what happens when it does go wrong. In a series of pictures of mutant creatures she then extended the principle to humans. The resulting images with their corporeal deformities and missing limbs are monstrous in the sense of being wholly other. This series investigated the transgressive nature of the monstrous, its ability to break down hierarchies and to challenge the boundaries of what is considered human.

By repositioning the nature of the interaction between human and animal, Braithwaite creates a fantastic world in which she can edit both human and animal, borrowing an attribute of one and giving it to the other. The result is a world where species barriers have slipped, in which are created hybrids that are simultaneously horrifying and humorous. Braithwaite has written that:

Rather than collecting specimens as [Mark] Dion does, I collect moments or instances when the interaction of animal and human reveals a flow of energy where the two connect or where there is an imbalance of power and one dominates the other.

JOANNA BRAITHWAITE Hard Nut from the Menagerie series 2001 Oil on canvas 150 x 180 mm.

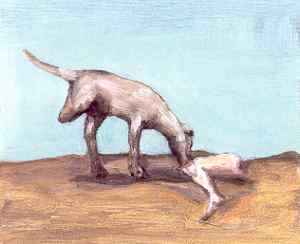

The 60 small paintings that make up her latest Christchurch exhibition Menageries work both individually and as a series. Inverting scale and power relationships, she presents us with a collection of episodes in which humans are dwarfed by birds and animals. In some a human being becomes prey, carried in the beak of birds in place of a worm, or tossed between two blackbirds. In others strange hybrids are formed, part man, part insect, the products of some nightmarish experiment. These paintings suggest strange and grotesque couplings between human and beast and as such convey the moral depravity of the hybrid creatures that inhabit Bosch's hell scenes. These works are also surreal, replacing commonplace associations with the unexpected. In Hard Nut (2001), for example, a squirrel holds a human head in its paws instead of a nut, the incongruity of the juxtaposition upsetting the expectations of the viewer. Tasty Mortal (2001) reveals a monstrous rat sniffing at a small human head. As you move from one to another, Goya's Disasters of War with titles like This is worse come to mind. In Dog Leg, a dog feeds off a severed human leg. The viewer experiences a shock of dislocation on realising that the dog is missing its own leg. These small paintings derive their power from a Goyaesque, anecdotal quality that powerfully conveys the indifference that the creatures, empowered by their size, display towards the human element. At the same time these paintings lack Goya's sense of despair. They are playful and humorous and the tiny people are shown as naked, vulnerable and slightly ridiculous. The aggressive protagonists in these paintings are male, and some, such as those fighting battles on the back of ants, sport tiny erections. None manages to retain their dignity. These paintings convey the mischievous pleasure the artist has had in toying with human and animal components in order to erode the difference between the two. In several there is also a deliberately naive quality that reinforces the impression of a documentary image, which is then subverted by the fantastic subject-matter. In Menageries, Braithwaite manipulates both the normal relationship between people and animals and insects, as well as the size of the relative protagonists, allowing them to play and breed in strange and macabre ways. The result is the impossible, and often horrific, made tangible, a fantasy of sorts and one that seems directed at puncturing the self-importance and complacency of the human race.

JOANNA BRAITHWAITE Dog Leg from the Menagerie series 2001 Oil on canvas 150 x 180 mm.

Braithwaite's fascination with the inversion of hierarchies and power structures and her pre-occupation with testing the limits of what is considered human, raises wider issues of identity and authority. Her paintings prompt physical responses by means of psychological narratives, while projecting the spectator into realms where they must question the nature of their existence and their relationship with those around them. By these means her work also serves to make visible the processes by which power structures and hierarchies operate in contemporary society.

1. Hannah Fink, 'Rosalie Gascoigne' 1917-1999', Art in Australia, vol. 37 no 4, 2000, p. 536.