In 1972 the first New Zealand television documentary about Len Lye was entitled Len Who? Interviews in city streets showed New Zealanders baffled by questions about an artist called Lye. In Christchurch, his home town, The Press spoke of the documentary as an introduction to a 'prophet without honour in his own country' (26 June 1973).

Over the years New Zealand has gradually shifted this artist from the margin to the centre, from obscurity to stardom. In 2001, the centennial of Lye's birth, activities around the country have carried his public reputation to a new level. According to Tessa Laird in the Listener (9 June 2001), 'Lye is not just the unsung maverick of New Zealand art, he's the unsung maverick of modern art, period.' And Mark Amery in New Zealand Books (October 2001) argues that 'Lye's work and example have proved, I believe, more influential to many artists and writers of my generation than the sterner, over-subscribed "prophetics" of the likes of McCahon and Baxter.'

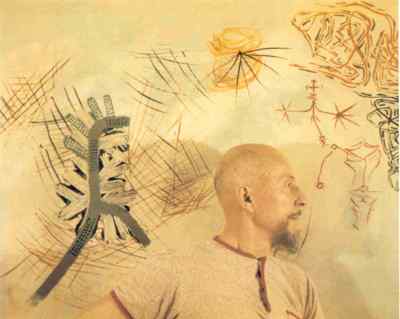

Len Lye in New York c. 1970 in front of his painting The King of Plants Meets the First Man 1937 (Photograph: Erik Shiozaki)

As Lye's career spans most of the twentieth century, the ups and downs of his local reputation provide clear evidence of changing attitudes within New Zealand art—attitudes to modernism, to avant-gardism, to expatriate artists, to film and photography as part of the visual arts, and so on. Today his exact place in the canon still remains a matter of debate. Major works continue to be built according to the plans and instructions he left at his death. Controversy has always rippled round him - from his days as a bad boy in London, the 'Futurist New Zealander' whose work 'caused a sensation' (in the words of The Sun, 19 May 1928), to the more than 200 newspaper and television items that debated the practicability and authenticity of the 45-metre Wind Wand erected in New Plymouth last year.

Before tracing the history of his reputation, let's make a survey of his centennial as evidence of his standing today. 2001 has seen exhibitions of films, paintings, sculpture and photograms. As further examples of Lye's diversity Wayne Laird is producing a CD from the sound patterns of his kinetic sculptures, and the artist's creative writing is showcased on a new website, the New Zealand Electronic Poetry Centre (www.nzepc.auckland.ac.nz). The first biography of Lye has been published, and his birthday on July 5 was marked by an enthusiastic message from Judith Tizard, Associate Minister for Arts, Culture and Heritage: 'I believe he was New Zealand's Leonardo da Vinci.'

The first Lye exhibition for the year was the New Zealand Film Archive's Len Lye: Colour Box, opening in Wellington on May 25 and later toured to the Archive's Auckland branch. Curator Lissa Mitchell had thought hard about how to exhibit Lye's films. While three films were screened continuously on video monitors, lightboxes displayed sample segments. The lightboxes froze an art of motion but retained the optical intensity of film projection. In Mitchell's words: 'I think it is important that people "see" that Lye worked on film, and I wanted to emphasise the importance of film as a material surface or canvas for him. I wanted to give people the chance to view Lye's films as he would have composed them...with the series of film frames functioning much like McCahon's panel paintings.'

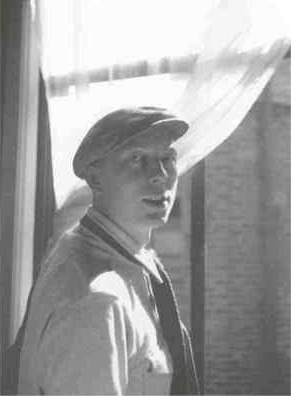

Len Lye in London, 1936, photographed by Barbara Ker-Seymer

In New Plymouth the 45-metre Wind Wand was returned to its original location on the shoreline in late June, approximately 16 months after it had succumbed to a storm. On Lye's birthday there was a community party round the Wand with a jazz band, and the red light at the top of the sculpture was again turned on. Later there was a party at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery where cocktail glasses were decorated with a swizzle stick in the shape of the Wand, with a cherry for the light! Other celebrations included a memorable speech by Jonathan Dennis whose struggle to establish the New Zealand Film Archive had been partly inspired by Lye.

Criticism of the Wind Wand in New Plymouth appears to have evaporated. Now, whenever there is a heavy wind, members of the public come to reassure themselves that New Plymouth's icon is safe. Children respond strongly to the Wand and some have been overheard urging their parents to take them to the Govett-Brewster to see other kinetic sculptures. Lye's work has an exceptional ability to penetrate popular as well as high culture. The local tourist website is called WindWand.com, and the widespread interest in creating backyard wands was demonstrated last year when a public competition organised by Lynn Webster attracted hundreds of home-made versions.

From July 5 the Govett-Brewster presented its largest Lye exhibition to date. The Long Dream of Waking took its title from an unpublished 1940s poem by the artist. Co-curated by John Hurrell and Hanna Scott, it represented a variety of media and illustrated the range of material in the Foundation's archive not previously exhibited. Trilogy, Lye's most dramatic sculpture, was renovated for the occasion. Filling the whole gallery, The Long Dream of Waking was organised around a series of themes including primitivism, automatism or doodling, and 'line and loop elements that seemed to be a substitute for the artist's own body'. Even though this was a high-powered exhibition that focused on Lye's art and aesthetics, there was an impressive total of 12,000 visitors during the seven weeks of the show. 52% of them came from outside the region, including many tour groups from Auckland, Wellington and Hamilton.

The gallery also launched a series of booklets on Lye in association with the Film Archive and the Lye Foundation. Aware there is still a shortage of in-depth or technical discussion of the artist's work, the Gallery and the Foundation joined with the Department of Film, Television and Media Studies to sponsor a one-day Lye Symposium at the University of Auckland on June 30. This demonstrated the wide range of critical approaches that Lye's work engenders, from papers on the theory and practice of art by Wystan Curnow, Hanna Scott, Wendy Vaigro and Jan White to the theory and practice of engineering by Shayne Gooch and Evan Webb.

The year has also seen an increase in the number of times Lye's work has been selected for theme exhibitions. Examples have included Think Colour, organised and toured by Pataka Porirua Museum, and To Die For, a selection of favourite works at the Dowse Art Museum. Overseas there have been a number of film screenings including a Lye retrospective at the University of California's Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. Still to come is a centennial Lye exhibition of films, sculptures and photograms at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, planned in association with Govett-Brewster. This opens in Sydney at the end of November and will later tour Melbourne and Brisbane. Though Lye spent several years in Sydney in the 1920s and was strongly influenced by Aboriginal art, this will be the first gallery exhibition of his work in Australia.

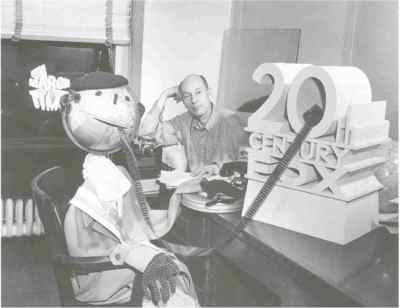

Len Lye in his office at the March of Time, c.1945. A new logo he designed for the series is on the left.

In general the centennial year and the synergy between so many different events has multiplied Lye's links with New Zealand culture. The description of his exuberant personality in Len Lye: A Biography has provided a point of entry for a wider audience. John Maynard made a wise decision in 1980 when he chose a photo of the artist laughing as the symbol of the Lye Foundation, in sharp contrast to our tradition of anxious images (to recall the title of an Auckland Art Gallery exhibition) or what Sam Neill calls 'the cinema of unease'. Lye is still being received as a fresh discovery and acknowledged as a missing link in our art tradition.

What kind of reputation did Lye have during his lifetime? In the 1920s he impressed his art teachers, H. Linley Richardson and Archibald Nicoll, and won prizes in the New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts competitions. However, when he began making sculpture in a modernist idiom, such as the marble 'Unit' or the wood carving 'Tiki', he appears not to have exhibited it. At that time it would have been hard to find an artist in New Zealand or Australia better informed about Futurism, 'modernist primitivism' and other avant-garde tendencies. But either his work was rejected or he saw no point in offering it. He was attracted inevitably to Europe. The next wave of modernists (such as Angus, Woollaston and McCahon, born between 1908 and 1919) would be the first to stay in New Zealand, though exhibition opportunities remained limited for many years.

Lye reached London in 1926. Its avant-garde culture was small but lively as shown by the speed with which the newcomer was invited to join group exhibitions. In 1928 there were newspaper reports of Lye's avant-garde activities. Reviewing a 7 & 5 Society exhibition, the London Daily Chronicle declared that Lye had 'stoked his way from the Antipodes to take London by storm' and 'His originality even surpasses that of his London colleagues'. Wellington's Evening Post brought similar news home under the heading 'Ultra-Modern Art: Herod Out-Heroded: New Zealander's Effort'. While this suggested some local pride in his extremism he was basically seen as a curiosity. In the 1930s the New Zealand press ceased to be aware of his work, though the magazine Art in New Zealand published one sarcastic description in 1933 describing him as 'a young Australian' and 'good joker' who was exhibiting 'peculiar panels' alongside the 'scrap paper efforts' of Ben Nicholson (Vol. 5 No.20, p. 238). At this time much of the reviewing of modern art in New Zealand still kept its tongue in its cheek. The only New Zealanders with a serious interest in Lye's work appear to have been the art educator Gordon Tovey and later the painter Gordon Walters.

In the 1930s Lye developed a reputation throughout Europe as a film innovator, with his work screened frequently by film societies and festivals as well as commercial cinemas. Its bright colours and jazz music appealed to general as well as avant-garde viewers. Lye gained a permanent place in film history as the pioneer of the direct method, making films without a camera by painting or scratching directly on celluloid. Time magazine ran a long story about this 'film painter' on 12 December 1939 describing him as England's answer to the production-line methods of Walt Disney. Nevertheless his films appear not to have reached New Zealand. While there was some film society activity in the 1930s the country lacked a tradition of art-related experimental film.

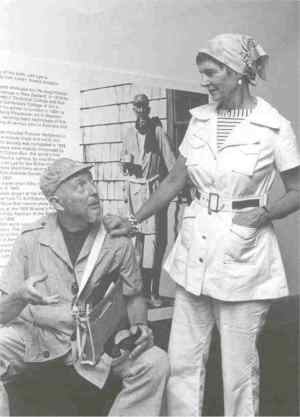

Len and Ann Lye at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery in 1977 for the opening of his exhibition (Photograph: Taranaki Newspapers)

In the 1950s and '60s Lye developed a new international reputation as a kinetic sculptor. The early '60s saw the first wave of serious interest in his work in New Zealand and it was no accident this came at a time when modernism was at last strong enough to challenge mainstream, traditional art on its home ground. Peter Tomory, the English-born director of the Auckland City Art Gallery, presented exhibitions of Henry Moore sculpture in 1956 and British abstract painting in 1958. As Jim and Mary Barr have documented in their book When Art Hits the Headlines, the Mayor of Auckland denounced the Moore exhibition as 'repulsive' and a 'desecration' of the gallery. These were heroic years for the struggle to gain institutional acceptance for modern art.

In the early '60s Tomory was delighted to hear about an avant-garde artist in New York who hailed from New Zealand. Lye retained warm memories of New Zealand's landscapes and its Maori and Pacific cultures, but he assumed its official art scene was still claustrophobic. He was surprised and delighted when a new generation of well-informed people from New Zealand began visiting him, starting with Tomory in 1964 who explained that the country was 'going modern in its culture'. Unfortunately in 1965 when Tomory took an application for a Lye lecture tour to the recently created QE2 Arts Council, it was not interested. When Tomory left the Gallery for a job overseas Lye saw it as proof that New Zealand still did not know how to hold on to its innovators.

But other supporters emerged such as Hamish Keith and Peter McLeavey who worked hard to spread the word about Lye. Also, the counter-cultural spirit of the late '60s encouraged a more open, multi-media approach to art, and Lye appealed to the younger artists as a wild ancestor, an alternative father-figure. A passion for the modern was often associated at this time with a heightened interest in international art - but not always for, as Hamish Keith explained, New Zealand artists 'weren't all that keen on making space for the expatriates because it was hard enough to find space for themselves'. No institution would fund a Lye visit. In Keith's words, 'Until people had actually met Len and seen his work, it was hard to generate any enthusiasm.'

Despite the lack of sponsorship Lye visited New Zealand in 1968. One result was that New Zealanders learned about Lye's film-making. Keith remarks: 'I was shocked to discover that Lye had preceded Norman McLaren in the production of direct films. McLaren's films had been the staple diet of the National Film Library, they were shown to us at school. And of course everyone here was led to believe that McLaren was the pioneer of drawing on film. It's another example of how New Zealanders . . . defer to other people and don't believe in our own powers of innovation'. Lye's films were a timely discovery since his visit coincided with the first stirrings of a more experimentally-minded film culture.

At 67 the artist was looking for somewhere to establish a second home where he could return to painting. He still felt a strong connection with the New Zealand landscape. But after his return to New York, the news he received from this country kept reminding him of his own struggles in the '20s. Keith had left the Auckland Gallery which seemed no longer to provide a base for the kinds of work that interested Lye. And so he turned to Puerto Rico and bought a house in Santurce which provided the studio for his burst of painting in the '70s.

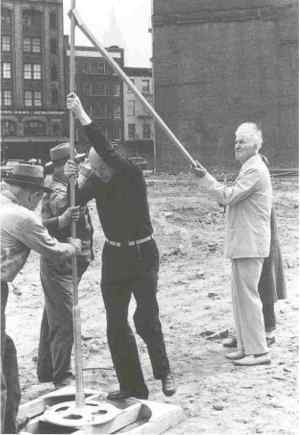

Len Lye errecting a 40-foot Wind Wand in New York in 1960 assisted by Robert Graves (in a light-coloured suit)

Some New Zealanders continued to campaign for a major Lye exhibition. When Ray Thorburn approached the National Art Gallery in Wellington in 1972 he was shocked by its lack of interest. He then looked for a provincial gallery with 'less red tape' and 'more imaginative thinking', and found them in the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. This remarkable provincial gallery continued to exhibit a wide range of contemporary art despite pressure to support more traditional and more local work. Its current Director was a Californian, Bob Ballard, aware of Lye's overseas reputation. New Plymouth could also provide the innovative engineer that the artist required for his kinetic sculpture. John Matthews established a close collaboration with Lye who was so impressed by the quality of the work and the support of the gallery that he decided to leave his collection to New Zealand, with a non-profit Foundation to administer it and the Govett-Brewster to exhibit it. Support followed from other local institutions, with the Arts Council and the newly-created New Zealand Film Commission funding Lye films.

The artist returned to New Zealand in 1977. Around 200 people attended the opening of his Govett-Brewster exhibition, launched by Hamish Keith who saw it as the climax of a long campaign: 'All I can say as Chairman of the Arts Council is that this is for me perhaps the most important occasion I've ever been asked to speak at.' Recalling Len Who?, he added: 'The prophet is with honour in our land!' Ann Lye wept at the sight of her husband's sculpture realised on a giant scale after so many years of frustration.

The artist died in 1980. The seventeenth issue of Art New Zealand, with Wystan Curnow as guest editor, served as a memorial and provided the first local source of in-depth information about his life and work. That year the Auckland City Art Gallery presented an exhibition of Lye's paintings (A Personal Mythology) which the artist had planned with curator Andrew Bogle. Although painting was not Lye's strongest medium, the exhibition was well received. But the Gallery's announcement that it was interested in erecting a memorial to Lye triggered off a public controversy. Objecting to this use of 'ratepayers' money,' art consultant Peter Vuletic alleged that 'the New Zealand public has been misled into thinking Lye had a considerable international reputation,' and that such over-valuing was a case of 'misplaced nationalism'. The Herald published a number of letters supporting Vuletic but there were also letters backing the memorial from Curnow and Keith. In the end the idea ran into practical problems and nothing came of it.

Debate continued through the 1980s, focusing on two questions: was Lye really an important artist, and was he relevant to New Zealand? Local encyclopedias and histories of art continued to ignore him. The first problem was the fact that the artist's areas of specialisation-experimental film and kinetic sculpture-were viewed as marginal to the mainstream of art. It didn't help that Lye had moved between countries and art forms so his overseas reputation was fragmented-there was an English Lye from the 1930s, an American Lye from the '60s, and (now slowly taking shape) a New Zealand Lye.

Dennis McEldowney in Then and There: A 1970s Diary documented the debate within Auckland University Press about whether the proposal to reprint Lye's No Trouble could be taken seriously. Some of the academics on the board feared they were being taken for a ride, as though claims for Lye were almost as dubious as those for Colin McKenzie in Peter Jackson's Forgotten Silver. To counter the scepticism it was necessary for the co-editors to compile a bibliography listing hundreds of overseas reviews and discussions of Lye's work. Figures of Motion, a broader selection of Lye's writings, was published by AUP in 1984 but it received mixed reviews and was eventually remaindered. Subsequent attempts to interest publishers in other Lye manuscripts were unsuccessful.

New Plymouth provided a steady base for Lye's work though resident artists sometimes protested that too many local resources were tied up in his work. Another problem was limited visibility. Initially the Lye Foundation interpreted the trust deed to mean that no work should be sold outside New Plymouth and this embargo is said to have been a factor in the Auckland City Art Gallery's decision to seek a kinetic sculpture by George Rickey as an alternative. Eventually the Foundation softened its stance. Also, it made Lye's films readily available on video.

Two more documentaries appeared—Doodlin' (made by Keith Griffiths for England's Channel Four in 1987) and Flip and Two Twisters (made by Shirley Horrocks for New Zealand television in 1995). An increasing number of people made the pilgrimage to New Plymouth. Painters started to acknowledge Lye's influence (such as Paul Hartigan, Philippa Blair, Stephen Bambury and Max Gimblett), and an avant-garde music group including composers Jonathan Besser and Ross Harris called itself Free Radicals. Lye's work continued to be studied by experimental film and video makers, and meanwhile his imagery influenced music videos and rock concert posters.

By the centennial year, art itself had shifted internationally towards multi-media diversity. Film, video and photography had gained in status (including Lye's photograms). The last two years have seen a revival of interest in kinetic sculpture, such as the large Force Fields: Phases of the Kinetic show at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Barcelona and the Hayward Gallery in London which used Lye's Blade as its poster image. Internationally it was a favourable time for a new generation to be introduced to Lye. In 2000 a one-man exhibition of Lye's sculpture, painting, photograms and films at the Centre Pompidou in Paris drew a sizeable audience and the museum produced a book of essays (Len Lye) by a range of international critics.

Meanwhile New Zealand culture became more open to such an artist. The local became more intricately connected to the global, and the New Zealand government promoted the idea of seeking out expatriates. This is not to forget that Lye is still 'Len who?' in some areas of the culture. For example the NZ Post Office ignored suggestions that he should have a stamp in his centennial year, and initially some large bookshop chains were reluctant to stock the biography of such an obscure artist. It is ironic that during the centennial year the Lye Foundation has faced its worst financial problems because of the cost of repairing Wind Wand. Nor has controversy ended, with Ian Wedde and Andrew Drummond questioning the authenticity of the large-scale sculptures (e.g. Sunday Star-Times, 30 September 2001). Lye had left his Foundation the task not only of looking after his existing works but also of building giant versions of his sculptures. He supplied detailed instructions as to the artistic effects he wanted but left the Foundation to sort out the engineering problems. The results to date have been extraordinary-thanks to the engineering achievements of John Matthews, Evan Webb and their collaborators-but the debate about authorship persists.

Lye himself worried about gaining too much acceptance and he warned his New Zealand admirers not to overstate his case because he feared a backlash. Nevertheless every country has its canon of artists and Lye deserves a place in ours, both because his work deserves to be better known and because our role models should include an artist with an experimental spirit as energetic as his. Again, Lye provides New Zealanders with a very positive example of the dialogue between the local and the global and the value of welcoming home expatriates and their art.

[Note: Quotes not otherwise attributed come from Roger Horrocks, Len Lye: A Biography, Auckland University Press, 2001. Photographs not otherwise acknowledged are couresty of the Len Lye Foundation. Further previously unpublished photographs are available in the magazine.]