Dear Editor

JUSTIN PATON

How do you take the measure of a tradition? I am holding my hand just above my right kneecap. That's one way of measuring Art New Zealand's legacy. Over the past week I have leafed through 99 issues, the shelf behind me emptying as the pile beside me grows, in a disorderly attempt to account for the arrival of the magazine's 100th issue. 'A tribute', says William's letter of commission. The brief makes me nervous, partly because the line dividing honest homage from anniversary cliché is so fine, and mostly because any magazine, if you stay with it for long enough, becomes a de facto scrapbook and family album. You can't sift through the journal boxes without calling up scenes-some pleasurable, some embarrassing-from your own private record of the time.

I first encountered the magazine amidst the bargain-bin acrylics and orange plastic lino-cutters of a state school art class. Crushingly literal-minded, the then art syllabus demanded that students find an artist model, and copy that sucker down. I recall number 39 (Milan Mrkusich on the cover) getting a lot of use by the Clairmont cadets and would-be Nigel Browns of the Shirley Boys High School art class. The colour, the look, the weight of those magazines merge in my mind with other art-room standards: Marti Friedlander's A-M book, with its aroma of turps and rye bread, and Kaleidoscope documentaries played back on speckly Beta videotape. In 1988, at the McDougall Art Gallery shop, I bought a copy-number 44, Toss Woollaston on the cover, who in Robin Morrison's lovely photograph leans toward us with the same stony presence as the mountain in the painting behind him-a human Mt Ste Victoire. I felt baffled as often as enlightened by the things the magazine contained, but you know what? That didn't matter. What mattered more was a tone, an air of intensity, a sense that urgent conversations were going on in a room somewhere nearby. And so I leaned in close to listen.

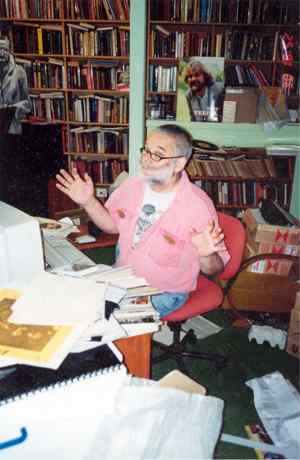

The editor at work

Later, when I'd begun writing for the magazine, I visited William and founding editor Ross at Prospect Terrace. New to Auckland, I walked, slowly sweating through the streetmap I'd drawn on a scrap of paper. I remember the big dazzle of Auckland's light, and wading through thick air up Newton Gully, an hour late. Probably distracted by some vision of magazines offices as swank top-storey hangars full of Aalto chairs, gurgling water coolers and sub-editors in green visors, I wandered into what was then the New Zealand Magazines building on the corner of Prospect Terrace. Art New Zealand, it turned out, was up the road. It was put together not on the lightboxes and whiteboards of a sun-drowned penthouse but in a warren underneath the kind of Auckland villa that Frank Sargeson might have set one of his sly late novels in. Its editor, William Dart, peered over his half-glasses with a mixture of wryness and battle-weariness, as might a person who has performed emergency surgery on countless maimed sentences and chased down hundreds of deadline bandits (I am remembering, right now, the ominously patient silences with which William more than once coaxed this writer into getting on with the job). His desk is, as anyone who has seen it will tell you, a space of relative calm in a catacomb of books, back issues, and precariously stacked compact discs-reefs of sheer cultural stuff that might keep a crack team of Masters Students busy for years.

Anyway, it was late in the day. I had a drink with Ross Fraser in a cool room upstairs while William got ready for a concert he was reviewing. Pale-eyed, quiet, a little shaken by a recent stroke, Ross was nonetheless passionate-parental even-about the fortunes of the magazine. Ross talked about the editorial battle against boilerplate prose: the battle was getting harder, he thought; the boilerplate thicker. I looked at the art packed on the walls of high-ceilinged rooms, a collection guided by principles not of 'taste' but love. Then William drove me back to the city. A little later Ross sent a nice card, and I'm looking at it now.

I offer this scene not because it is remarkable but precisely because it's typical. It's this simple: a lot of writers got their start in the pages of Art New Zealand. Behind those big figures-100 issues, no less-lie many small acts of hospitality, patience, generosity. There's proof of that commitment in the stack of magazines beside me, or in details as ephemeral as the numerals on the top of William's close-to-deadline faxes: 3:42am reads one still in my files. The genial chaos of the office, the garden-shed scale of the enterprise-perhaps all of this should have been a letdown, an anti-epiphany. But it never felt that way. What I loved about the Prospect Terrace office-what made it seem interesting and even courageous-was the life in art that it embodied and promised. Not a life governed by 'career goals' or 'professional outcomes', which are the terms by which so much labour is measured and graded today, but what Dave Hickey calls a life in the arts in real time. A way of work that is a way of life.

It emerged in 1976, at a moment of perilous optimism in local magazine publishing. There was, elsewhere in the seventies, the valiant Photoforum, the shaggier Spleen, and occasional coverers of the visual arts such as Islands and Landfall. Three years later Alister Taylor's The New Zealander strode on stage, all full-colour Cultural Ambition, and just as suddenly vanished. Surer of its audience and less horizon-sweeping in its hopes, Art New Zealand started strong (six issues a year in 1976), calmed down a bit (by 1977 it was quarterly), and then just kept on. (Ross tells the story in Art New Zealand 50). Nothing lush by today's standards, those early issues nonetheless looked elegant in a context where many catalogues and periodicals still had a whiff of the gestetner and carbon paper about them. With its colour selections, no-nonsense Helvetica and Optima, and reticent editorial style, the magazine put 'New Zealand art'-wherever and whatever it was (and is)-in a professional frame. More, by creating a mouthpiece for the country's first generation of professional art historians, Art New Zealand helped to bring 'New Zealand art' into being as a subject for debate.

The covers that almost were - selections from Ian Macdonald's photoshoot for the cover of Art New Zealand 28 (1983) featuring Gretchen Albrecht, Stephen Bambury, Max Gimblett, Richard Killeen, James Ross, Ian Scott and Mervyn Williams

You can flip through a full run of Art New Zealand for a time-lapse movie of an art world on the grow. Young turks slowly become their own parents. The old semi-bohemian art world, with its hessian walls and mutton-chop sideburns, gives way to today's art world, the managerial model: black-suited, serious, strategically planned. There's a thesis to be written about the covers alone, charting the course from Pat Hanly's pirate pants to Luit Bieringa's skinny leather tie and onward past Mervyn Williams' gunslinger stare. Reputations sputter and rise through the ads, whose styles-from the graveyard chic of Peter McLeavey's full-pagers to the Pagemaker-baroque of newer arrivals-are themselves signs of the times. Magazines can be art history's outriders, ranging ahead and sighting fresh tracks. They are also, the further they recede from the present, poignant and funny archives of the way things were. It's easy to laugh at such a record (stilt theatre, anyone?), but there's also something bracing about these fluctuations and disappearances, so insulting to our confidence in the present.

As the ruined spines of most public library copies will attest, many of those early issues keep on resonating. Art New Zealand achieved its greatest amplitude in its special issues: on Len Lye, say, or art and the environment, or New Zealand photography, or Maori art today. I've heard it said that the magazine lacks focus, and I've heard myself agreeing at times. If I could make a birthday wish for the magazine, it would be for a patron to drop from the sky the kind of funding that might free the magazine not just to record events but to make them: to recover some of that focus. Still, one of Art New Zealand's chief values has been its lifelikeness to the din and dispute of the art world, which is really dozens of overlapping art worlds. For 25 years it has been a kind of Community Notice Board, positioned halfway between readers and artists and, like any good Community Notice Board, it has hosted some telling collisions of taste and tone: expressionist brush-tizzies share a spread with wholemeal minimalism, which is followed, over the page, by some multi-media barnstorm.

I'm not here to pretend that the magazine has run angelic prose from cover-to-cover, or that the captions haven't misbehaved occasionally. The memorable essays are sandwiched between the usual thicknesses of the rote and the dry. But many artists have received in its pages the kind of sustained appreciation that just is not condoned in newspapers or mainstream magazines, where art criticism, when tolerated at all, has become the puny sidekick of 'lifestyle' reporting-the lesser half of that bizarre hybrid known as 'arts and leisure'. If there were a publisher on hand with the wits and courage to back it, they could fill a small but telling collection with the magazine's best moments.

We might imagine that collection as a room, in which writers of wildly varying sympathies bump up against each other in illuminating ways. There's Ian Wedde, juggling paradoxes up at the bar. Over there David Eggleton is riffling through his bumper-edition thesaurus. Lita Barrie prowls the edges, menacing the regulars with imported technology. Francis Pound looks down from a high table, coaxing another sub-clause into a sentence. Up on stage, Tina Barton's doing karaoke Rosalind Krauss. The hard-core historians are in beige at the back of the room, hunkered down over their card indexes like veterans at a Housie night. From a booth nearby their students look on-faces lit by the glow of laptop screens-and begin to eye the elders' table enviously. There are flighty poets and starchy professors, eurekas and harmonies, mumblings and squabbles. Did so. Did not. It's a passion play, or a comedy, or perhaps a soap opera. Call it Neighbours. Or maybe Close to Home.

These harmonies and disharmonies don't just happen. Someone has to make room for them to sound. Someone has to pick up the phone, organise the pictures, send the faxes at 3.42am. A bigger and less art-allergic culture than it was when the magazine began, New Zealand today is still a tough place in which to keep an art magazine alive, as the long list of casualties suggests. For an instant index of how things have changed, check out the staff listing in one of Art New Zealand's early issues. The magazine had two editors, a business manager, a contributing editor, a designer, an advertising manager, and another ad rep. It still does, of course, but they're all called William Dart. Here, beside me, is the evidence of his and Ross's life and work: a wonky column of ninety-nine issues, a listening post for anyone who wants to hear one story of how and where the art was. The issue in your hands caps the effort. Put it down for a moment, and put your hands together.